Lines drawn: Redlining, racism and point system riddle Pointes’ pasts

December 13, 2019

During former Tower adviser Bob Button’s tenure at South, the newspaper staff participated in a school exchange with Denby High School, a predominantly black school in Detroit for one day in 1994. Instead of interacting while sitting in the library, the Grosse Pointe kids sat to one side and the Detroit kids to the other, Button recalled.

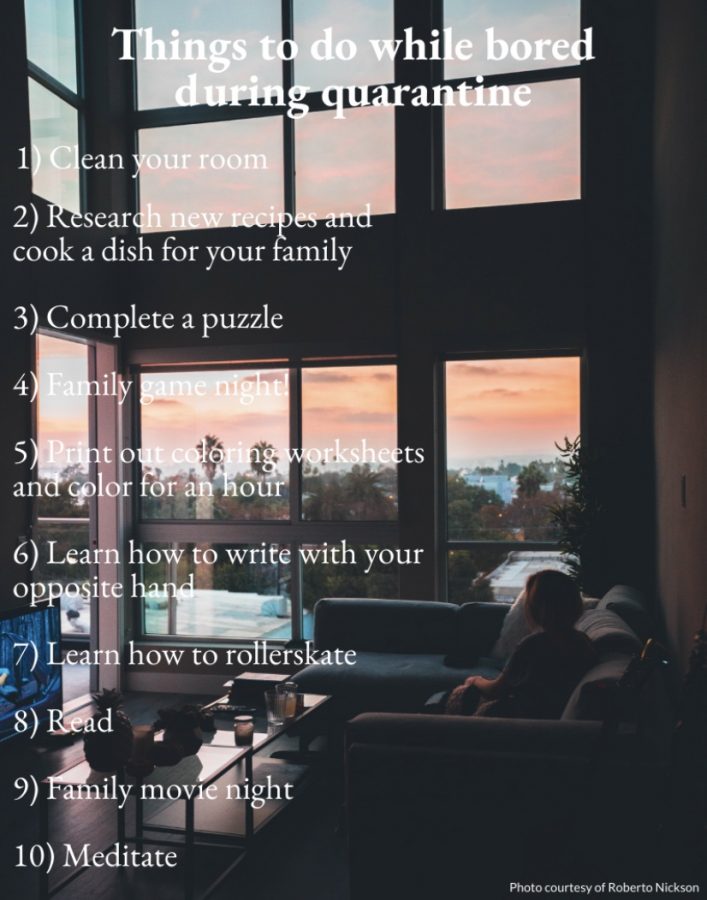

At the conclusion of South’s first Culture Week and the dawn of a new decade, Button emphasized the necessity of recognizing and challenging our complicated Grosse Pointe history.

One of the Tower students wanted to attend the trip, but his mother refused to sign the permission slip, because “she was not going to sign for her son’s death,” Button remembered the student saying.

According to Button, these sentiments grew from a historical separation of identities.

“Yes, there was some integration in Grosse Pointe, but it was not common and acceptance was not universal,” Button said. “There was apprehension.‘This is a different community, and we don’t know what life is like there.’”

In 1934, the Grosse Pointe Property Owners Association was founded in order to protect the property values and image of the city, according to “Grosse Pointe, Michigan: Race Against Race”, a nonfiction book written by Kathy Cosseboom ’63. The first African American family didn’t move into the city until July of 1966.

“There was no diversity,” Button said. “The school was entirely white; certainly the student body was entirely white.”

A point system, devised by the Property Owners Association, was the “formal means” for discrimination, according to Cosseboom. Private detectives would complete forms on behalf of the association regarding prospective Grosse Pointe residents.

These questions, according to Cosseboom, included: “If not American Born, how long have the applicants lived in the country?”, “Is their way of living typically American?” and “Dress— neat, sloppy, flashy or conservative?”.

The maximum score for the questionnaire was 100. According to Cosseboom’s research, a score of 50 was acceptable for most prospective residents. However, a score of 55 was necessary for Polish people, 65 for Greeks, 75 for Italians and 85 for Jewish people. Asian and black Americans did not receive ratings.

“It was a very, very tightly closed community at that time,” Button said. “It was the way things had always been, and it was the way people generally liked it.”

When the Detroit race riots occurred in 1967, Button said race became a topic that was addressed more. Along with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking at South in 1968, some new viewpoints, especially those of students, were elevated.

“It was a time of radical protests against systems that young people didn’t like,” Button said. “They were set out to change the world.”

As slight integration began, in 1968 a Tower poll of 202 students from across all grades and sexes about the integration of the Pointes showed the following results: 30 percent “approved of Negroes in their own neighborhood”, 27 percent would “have no reaction”, 18 percent would “encourage it” , 17 percent would “oppose but accept it” and 8 percent would “violently oppose it.”

One student responded that a black resident would be “lynched in a week by the mothers.”

South teacher Jeanne Dolson ’73 said she doesn’t remember any students of color in her classes, but she did not take notice of it at the time. Much of the segregation in the area can be attributed to redlining, defined by author Richard Rothstein as a system of refusing to insure mortgages in and near African-American neighborhoods while simultaneously subsidizing builders to build subdivisions for whites without selling any of the homes to African-Americans.

“I didn’t really know of redlining in high school,” Dolson, whose family took part in the white flight out of Detroit in 1968, said. “I didn’t learn of it until later on, and then it kind of made sense.”

Doctor Jay Marks, a diversity and equity consultant, has worked with students and faculty in the GPPSS on how to teach and support students across different identities.

Marks said the end of institutions like redlining and the point system did not represent the end of segregation.

“If policies have forbidden certain groups of people from moving into communities, they won’t move here, even if those policies change,” Marks said. “They don’t believe they will be safe or welcomed into the community. Knowing the history prevents people from wanting to move there in the first place.”

In the high schools, there was a lot of talk regarding integration through busing, according to Dolson. She said some violently opposed it, going so far as to bomb school buses. According to The New York Times, ten buses were destroyed using dynamite by former Ku Klux Klan members in Detroit with the intent to stop plans of racial integration.

“Governors proposed ideas of cross-district busing to integrate Detroit Public Schools because of white flight. It was very segregated,” Dolson said. “People fought against it. It was really ugly. I remember the headlines when I was in high school.”

Parental views have a large impact on their students’ mindsets, according to Dolson. She said she became more aware of different identities and opinions by leaving Grosse Pointe and going to college.

“My parents had more of an effect on my thought processes and ideas,” Dolson said. “When I went to college, I started reading more and (becoming) exposed to more people. I became more educated.”

School social worker Douglas Roby ’82 didn’t experience discussions about diversity, or lack thereof, when he attended South. Events like December’s schoolwide Culture Week “were not on (South’s) agenda,” Roby assured.

“I environmentally had a narrow-minded view of the world, which has dramatically changed,” Roby said of the effect of his time at South. “We’ve (South) taken a lot of steps in the right direction, but the whole awareness piece is still important.”

Since coming back to South and working here for 13 years, Dolson has witnessed major changes. According to Dolson, students are more aware of issues regarding gender, sexuality and race, and this has broadened their worldview already.

“(South) is more diverse and more kids are accepting,” Dolson said. “Society is more accepting. It is great (to see it) now, and (students’ mindsets are) getting better all the time.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Grosse Pointe Farms is 94.3 percent white, 3.3 percent black, 2.9 percent Latino, 1.3 percent Asian and 1 percent mixed.

Students of color in Grosse Pointe often don’t feel represented in school, according to Akira Benson ’20. Being half African American and half Japanese, he said he tries to not be affected by being an outlier.

“There are not many minorities here, so you see yourself on your street, on your block, and you could be the only (person of color),” Benson said.

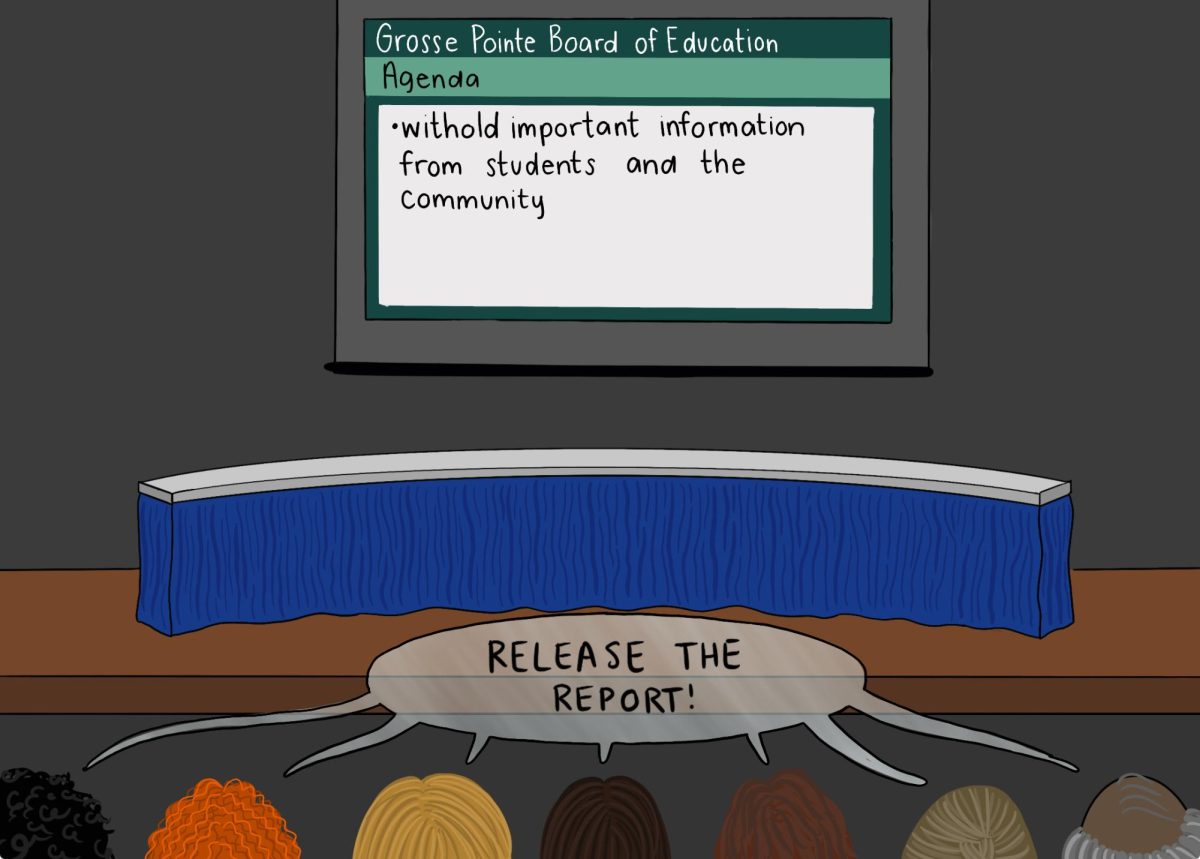

Marks said there are disparities in education caused by Grosse Pointe’s housing discrimination in the twentieth century that still need to be addressed.

“From a historical context, our schools have not been designed for everyone,” Marks said. “Now that we are trying to be inclusive to everyone, what institutional policies are we changing? It is not just about classroom practices, but also about our policies. What are the policies around zoning? Who gets to go to what school? Who gets to take Advanced Placement or honors classes, and who is not afforded those opportunities?”

Benson noticed throughout his time at South leading up to senior year that his learning experience has been centered around white people.

“A lot of African-American people and other people contributed a lot to society, and (the curriculum) just doesn’t show that sometimes,” Benson said. “More minorities should be in the curriculum.”

Marks said the lack of representation doesn’t allow minority students to feel “welcomed, included and safe.” He said this hinders their ability to learn in the classroom environment.

“Teachers must have the capacity, level of understanding, body of knowledge and skills to support their students,” Marks said. “They need to know how to respond to them effectively and how to respond to their cultures effectively through the way they teach.”

The state of Michigan Board of Education passed a resolution in 2011 focused on the importance of diversity in education. The resolution promises “the State Board of Education will continue to promote diversity learning in public forum.”

The responsibility to create change is on everyone, according to Marks. He said all factions of the community, including administrators, school board members and parents, must be dedicated to promoting a diverse learning environment for students.

“If you don’t have buy-in from everyone, it slows down the process,” Marks said. “If we are not willing to change policies and past practices that were based on institutionalized racism, then we are not doing much.”

According to a poll of 68 students by @thetowerpulse, 56 percent of people did not know what redlining or the point system were. Marks asserted that it is increasingly important to be aware of our community’s history in order to grow.

“All of our public institutions in this country are based to support the dominant culture,” Marks said. “They are not designed to be equitable or create spaces for different groups. We need to recognize this because it helps us develop our strategies and approaches (for) eradicating injustices.”

Timothy Place • Jul 1, 2020 at 6:20 pm

I ran into this article while researching racism in Grosse Pointe. Very well composed and written, very good journalism! I frequently read the NY Times, the Atlantic and the Guardian, and your article was as good as anything I’ve read there. I graduated GPHS 1968, and am trying to fill in memory blanks about the ML King speech of March 14, 1968 among other things. Does the Tower have records of that article? If so I’d love to see it. Keep up the very good work, journalism is in very good hands!

Elisa Gurule • Jun 2, 2020 at 9:22 am

I would like to know if Bob Button (i seem to recall his name) was the advisor who approved the inclusion of “Budzyn & Nevers” in the Top Ten list of things to be for Halloween in the immediate aftermath of the Malice Green murder. I was a sophomore at South at the time, so it must have been late ‘93. Grateful to see this new generation of South students putting their tremendous intelligence and resources into this kind of reporting. Thank you for your work, and wishing you the best as you move forward in life.

Kathy Ryan • Dec 14, 2019 at 8:17 am

Very good article on a very timely subject. Just a small correction….I believe the name of the school the Detroit students came from should be Denby, not Denny. It is still open and is located on Kelly Rd.