Perfectly Imperfect

The terrorizing cycle of perfectionism and anxiety

October 13, 2021

On the surface, the word “perfectionism” seems like a gift.

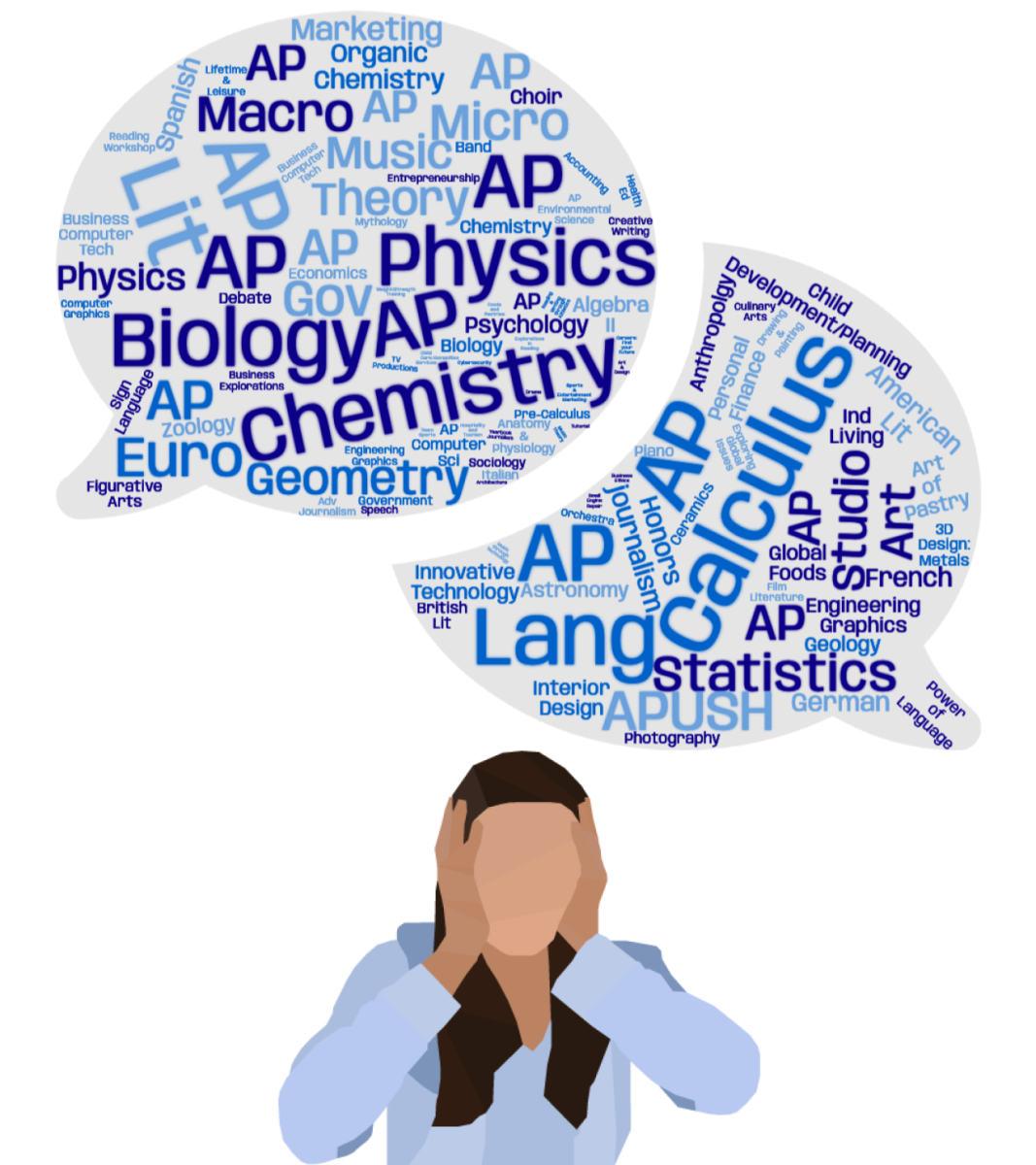

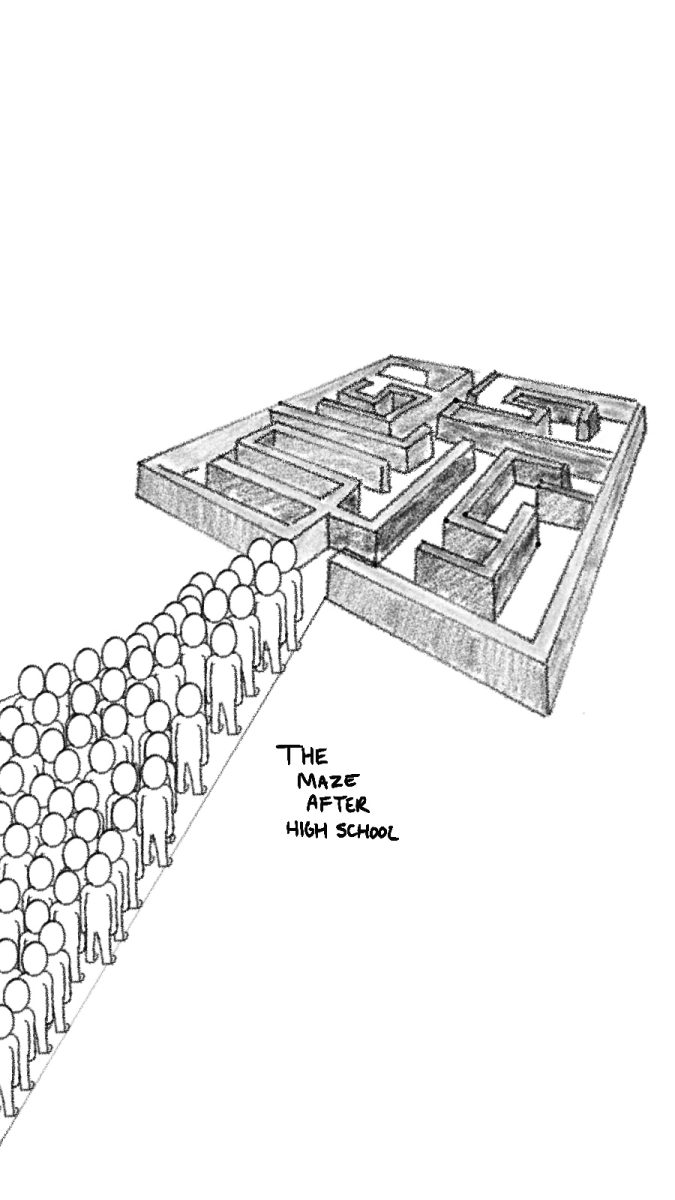

An unhinged drive to be perfect, pushing to do everything right each time seems ideal for the majority of people who don’t struggle with perfectionism. But the darker spiral of anxiety and self-depreciation that its victims experience tells a tale of losing control, when control is all any perfectionist could want.

Psychologist and therapist Dr. Andrea Andrzejczak says perfectionism tends to be caused by low self-esteem, and in turn aggravates teens and their mental health. She says this is primarily due to the large amount of moving parts that drown teenager’s abilities to cope with previous issues regarding anxiety and self-esteem.

“The person they’re trying to achieve is what they perceive to be perfect,” Andrzejczak siad. “It stems from their low self-esteem and anxiety. I think it (perfectionism) can be exacerbated in teens because of social media and the pressures to achieve and to get into college.”

Ellen Martin, therapist and founder of Starting Pointe Therapy in Grosse Pointe, says there are numerous factors for individuals to consider in terms of attributing perfectionism and finding its roots in a person. She says it can vary from person to person, but will typically start with a superior figure sculpting certain ideas in someone else’s mind.

“Let’s say it’s a child, and they receive the narrative or the messages from (their) parents (saying that) ‘nothing less than an A is good enough’, or ‘you have to be the best at everything,’” Martin said. “That child is going to internalize those messages and then start to incorporate them into their own value belief system. Since they’re not hearing the messages, ‘it’s okay not to be perfect’, ‘it’s okay to fail’ and ‘we actually learn a lot from our failures’, they don’t start to develop those into their sense of self.”

Eva Teranes ’22 said she seems like most teenagers her age, walking down the crowded halls to her next class and actively working on homework to manifest an A. However, she said her own perfectionism becomes aggravated due to social media and the impossible standards it has set for her. The non-authentic nature of the posts she sees has created a large spectrum of struggles for her.

“I think when you’re looking at social media and you’re feeling like you need to be a perfectionist, you’re trying to live up to someone else’s expectations,” Teranes said. “You feel like you can’t live up to that, and you can’t accomplish it because what you’re seeing on social media can be fake. It’s not real. You know it’s the best version of people’s lives.”

Lyla Pascke ’22 said perfectionism can be its own worst enemy. She said burnout can be a part of perfectionism, and from personal experience, it can be a challenge to deal with.

“When I was younger, being a perfectionist kind of helped because it made me go above and beyond,” Pascke said. “A lot of people have experience with it. As you get older and you start doing more and more to be ahead of the game, you start to fall off, and you feel like you’re not doing enough. Then you’re trapped in this cycle of trying to do too much all the time and anxiety factors into that because anxiety is what happens when you feel like you’re not being perfect.”

Andrzejczak said perfectionism is a coping mechanism for anxiety. She said perfectionists have an initial misconception that achieving perfection would alleviate any feeling of being out of control, but the aftermath leads to a cycle of the opposite.

“You’re always in a state of not feeling good enough when you’re a perfectionist, and you don’t achieve perfect because you never can,” Andrzejzcak said. “You are in a constant state of low self-esteem. (You tell yourself,) ‘I didn’t do good enough’, ‘It’s not good enough’, ‘I’m gonna get fired.’ You’re always in your head. You don’t live your life, and that impacts everything: going to school, working and having a family. You are not present.”

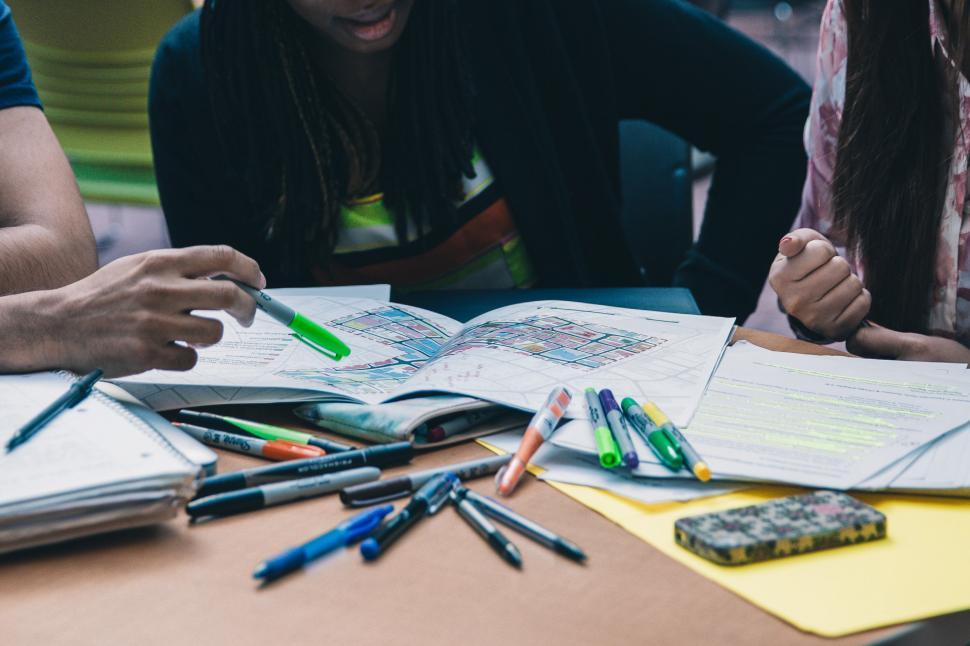

Henry Fish ’23 said perfectionism and anxiety can feel paralyzing in school or social situations. Setting standards way too high and relying on those standards to be approved by peers can be a stark contrast to the collaborative learning environment many classrooms at South provide. Fish said he has faced his own struggles with the social element of school.

“Anxiety definitely affected my educational status more than my personal life because I get very anxious about doing projects with people,” Fish said. “Because I don’t tend to get along with people and be able to talk to them, I feel kind of trapped (when working on group projects).”

Teranes said a lot of her own experiences with negative social situations due to anxiety have happened in school. She said the turbulent nature of putting more pressure on yourself in front of others can provide a mental stunt, sometimes at the worst times.

“Anxiety can make you take a backseat to your life,” Teranes said. “It can make you step back from things,especially when it comes to social anxiety. Going into the building is hard. It is already hard for me. I’ve had issues with speaking in class. I’ve had problems with presentations, group projects, anything like that. I’ve had a lot of problems with panicking it the moment.”

Fish said his anxiety is both the aggravator and the cause of some of his feelings. Ignoring the problem altogether seems like an optimal solution, he said, especially when the thought of anxiety alone causes him to worry.

“I cope with it (anxiety) by not coping with it,” Fish said. “The more that I tend to think about it, the more I feel anxious about whatever I’m worried about.”

Andrzejczak said the best way to deal with perfectionism is to identify, accept and work through it. According to Andrzejczak, by reversing the cycle and identifying the problem instead of using it, perfectionists can better understand how they work through both anxiety and their stem-rooted ideas of being perfect.

“I would tell them (perfectionists) to go to therapy and understand what they’re anxious about,” Andrzejczak said. “That is the start of the process. If they can understand their anxiety, then they can find adaptive coping mechanisms.”