Annabel Ames ’14 | Supervising Editor

On her nightstand, Lisa Monette has a framed picture of Nickolas, her youngest child who has Down Syndrome, in the intensive care unit of Children’s Hospital at ten weeks old, covered in tubes, blood and bandages from an open heart surgery.

“Every morning I wake up and remember those times because I never want to forget how far we’ve come,” said Lisa Monette.

When Lisa, who was 14 weeks pregnant at the time, found out that she would be having a baby with Down Syndrome, she was “scared” but threw herself into preparing for her son’s birth and future, she said. The Monettes have three other “typical” children, Olivia ’13, Abby ’15 and Grace ’17, and knew that raising a cognitively-impaired child would require hard work, but work is what they did.

“A typical kid will just get up and walk: we had to teach him how to walk,” said Lisa Monette. “Little babies put Cheerios in their mouth: we had to teach him how to feed himself. We had to teach every single step of development. We are always taking him everywhere and exposing him to as much as we can because it’s important for his development.”

At five years old, Nickolas Monette has gone under the knife more times than most people will in their entire lives. He had an open heart surgery at ten weeks old when he weighed only ten pounds, four hand surgeries to separate fused skin and will be having another hand surgery in the next few years, Lisa Monette said.

Along with the various health complications after his birth, the Monettes were told that Nickolas would be unable to do many of the things that he does now, including reading, Lisa Monette said. Not only can he read, but he has also learned around 50 sight words, can count to 20 on his own, knows his letter sounds and can recognize numbers.

But, as thrilled as the Monettes are with Nickolas’ developmental progress, they constantly worry about it being reversed because of his current education situation, Lisa Monette said.

“I feel like we’ve already fought too hard for him to be alive that we have to make sure that he has the best opportunities he can,” said Olivia Monette ’13.

Right now, Nickolas attends Barnes Early Childhood Center where he is in classes with other students with mental disabilities, Lisa Monette said. The Monettes opted for Nickolas to have one additional year at Barnes, and are concerned about whether or not the School Board will approve changes to the special education program before he attends elementary school next fall. They want him to be placed in a General Education (GenEd) classroom alongside students without disabilities at Kerby Elementary School, the family’s home school.

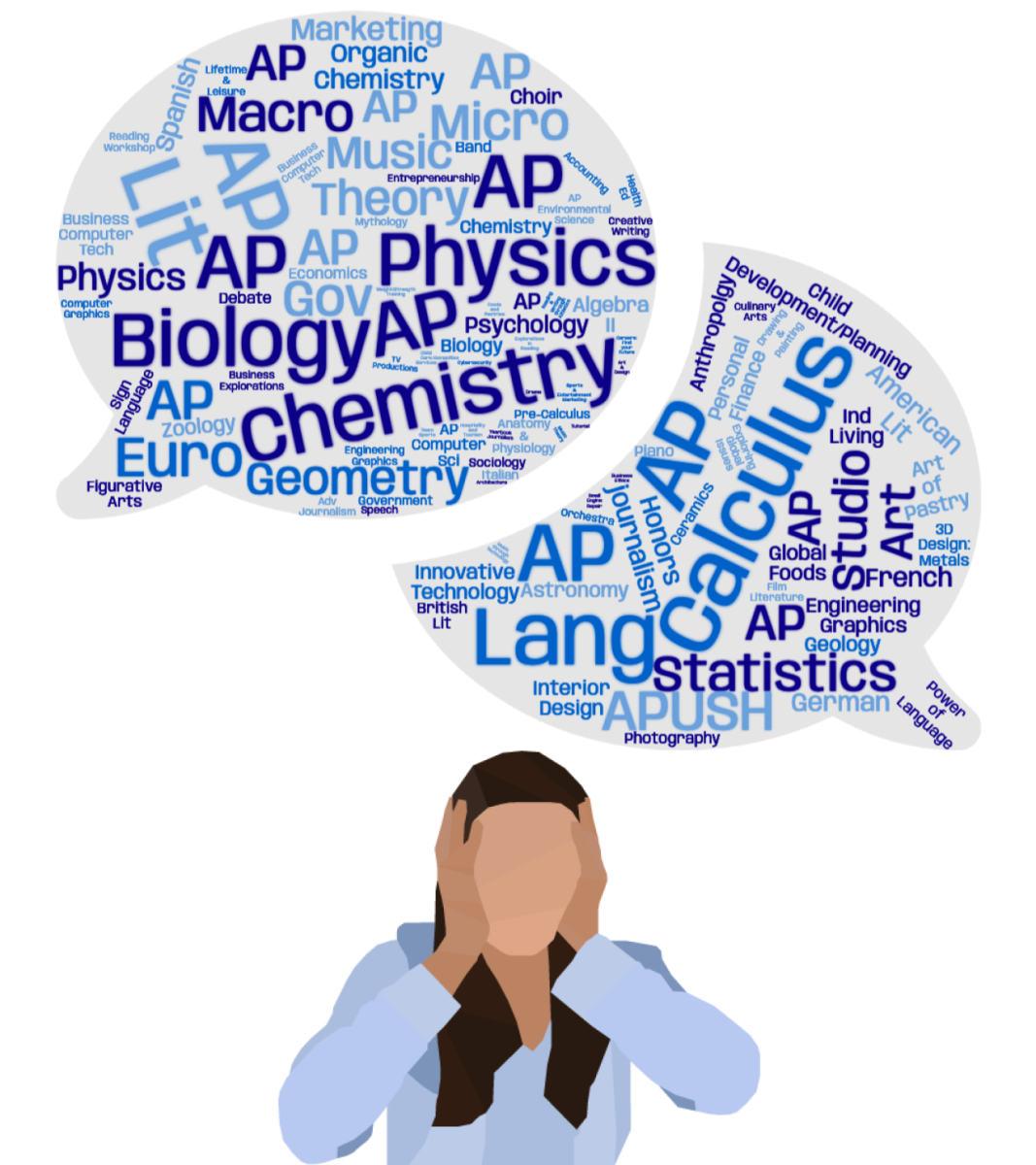

Typically, children with Down Syndrome attend preschool at Barnes with other cognitively-impaired children, then travel on to Cognitively-Impaired (CI) classes at Ferry Elementary School (with the same group of mentally-impaired students they attended Barnes with) where they are mainstreamed for a limited amount of time each week with “typical” children. Most then go on to Parcells Middle School and North High School.

Because several local families want to see special education reform in the Pointes, the Monettes and a parent advisory committee of about ten local parents of children with Down Syndrome recently came together to create a Facebook page called “Support Inclusion for Children with Down Syndrome in Grosse Pointe Schools”, Lisa Monette said. The parents in the group with younger children are focused on getting an existing preschool in the Grosse Pointe Public School System to allow children with Down Syndrome to attend, because none except for Barnes include cognitively-impaired students (where they are still segregated from their “typical” peers). The Monettes, who have the oldest child in the group, want additional elementary options for Nickolas other than Ferry, where he would be placed in a CI classroom.

“It (Ferry) is a great program, but I just don’t feel like it’s right for every child with Down Syndrome,” said Lisa Monette. “I want Nickolas to hang out with ‘typical’ kids and make relations. We have more patience because he’s part of our family, and, if he were in a typical classroom, 24 kids would get the gift that I got.”

The group does not want to change the existing special education program at Ferry, but want to have other elementary and preschool options that would allow their children to learn alongside “typical” children, Lisa Monette said.

In addition to wanting their kids to be in a GenEd preschool in the district and to have elementary options other than Ferry, parents in this group request more inclusion in determining their child’s Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) during Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meetings, Lisa Monette said.

The IEP meetings are held annually to determine the child’s LRE and their progress, the Director of Student Services Stefanie Hayes said. The mandatory attendees include the child’s parents, their special education teacher and a general education teacher. Additional attendees can include service providers such as speech and language pathologists or occupational and speech therapists, a school psychologist and a social worker.

“The LRE is different for every student,” said Hayes. “It’s where the student can get their individual needs met, and access the GenEd curriculum and GenEd peers as much as appropriate determined by the IEP team.”

Though some parents are happy with the existing special education program, many have said at School Board meetings that they want to have more of a voice in figuring out their child’s LRE.

“There isn’t a percentage,” said Hayes, regarding the amount of parental input in determining the LRE. “It’s not like the parents get 50 percent of the say and we get the other 50 percent. It is a team effort to talk through the needs of the student, and the IEP helps drive that by looking at their present data, their goals and objectives and what types of supports and accommodations are needed.”

Members of the inclusion group have presented speeches at School Board meetings and said they feel that their child would be best in GenED classes among “typical” kids, though their IEP meeting recommends CI classrooms with other special education children.

“The sooner kids with Down Syndrome are with ‘typical’ kids, the more comfortable they get with larger groups—if they’re in a class with 20 other children screaming and yelling and playing, they’ll get used to that environment and they’ll learn,” said Lisa Monette. “Down Syndrome kids typically mimic other kids’s behaviors, and, as a parent, that’s what you want.”

The Monettes have seen the benefits of GenEd classes firsthand, Lisa Monette said. After three years of pushing, they finally convinced St. Paul on the Lake Catholic School (St. Paul) to allow Nickolas to spend two and a half hours in a GenEd preschool three times a week.

Nickolas is thriving around kids without mental disabilities, Lisa Monette said.

“The teachers kiss him and they hug him and he has friends—he just got invited to a birthday party and when he got to the party it was like he was a rockstar,” said Lisa Monette. “When I pick him up, he’s laughing. We can see the positive effects of being in a normal classroom.”

Though he learns differently from other children, Nickolas comes home from St. Paul preschool excited about the material they covered in class, Lisa Monette said.

“You don’t ever want to take an opportunity away from a child because you never know what they’re capable of until they’re in that situation,” said Lisa Monette. “And, at some point, it might be too much for him and I might need Ferry, but let me just try. That’s all I’m asking for, one year at a time.”

If children with Down Syndrome were to be integrated in GenEd classes, “typical” children would benefit from learning and playing with students that are slightly different from themselves, Olivia Monette said.

“It’s important for kids to not be ignorant to differences in other people,” said Olivia Monette. “If you’re just with your normal friends all the time and you see someone who’s different, you’re going to be afraid of them and shy away. But he’s more alike than he is different: he reaches milestones later, but otherwise he’s the same.”

Several of the families advocating inclusion have “typical” children in the district already, and do not want to have to move to find a better special education program for their child with Down Syndrome, Lisa Monette said. While many are happy with the education of their “typical” children, families in this reform group feel that the district is behind in the times for kids with disabilities and want to see changes that will include their children in GenEd classes.

“Seeing how far he’s come in five years and how many milestones he’s overcome, we don’t want him to just be in a classroom with other kids with special needs and regress,” said Olivia Monette. “We want him to accomplish as much as he possibly can and be given the tools to reach all of his goals, not just stick him in a room with kids that are the same as him. You work so hard for every goal and we’ve seen how much he’s accomplished, it makes us wonder ‘what else can he do?’”

Though they are willing to do whatever it takes to get Nickolas into General Education classes, the family wants the school to welcome him with open arms without a fight, Lisa Monette said.

“I want him to go to Kerby, but for him to have success there everyone has to be on board,” said Lisa Monette. “I don’t want to fight and make them take him, and then nobody wants him. Everyone from the principal to the janitor to the lunch mothers have to be on board for him to be successful.”

In the future, the Department of Student Services hopes to increase communication with parents, Hayes said.

“Our department is dedicated to progressing,” said Hayes. “Our growth as a department is a process, and we do want our kids to be accessing their GenEd curriculum and peers as much as possible, and we have a responsibility to make sure that we’re doing that. We want to get better at what we do.”

As Nickolas continues to make leaps and bounds of developmental progress, the Monettes have high hopes for his future and remain optimistic that the School Board will see the benefits of making necessary changes to the current special education program, Lisa Monette said.

“In the fall of 2014, I want him standing in line with all of the other kids at Kerby waiting to go to kindergarten class. I want to walk him to our home school, stand in line and watch him go through the doors with all of the other kids,” said Lisa Monette.