The hidden danger of spreading a false narrative

A closer look into the damage of misinformation

September 27, 2021

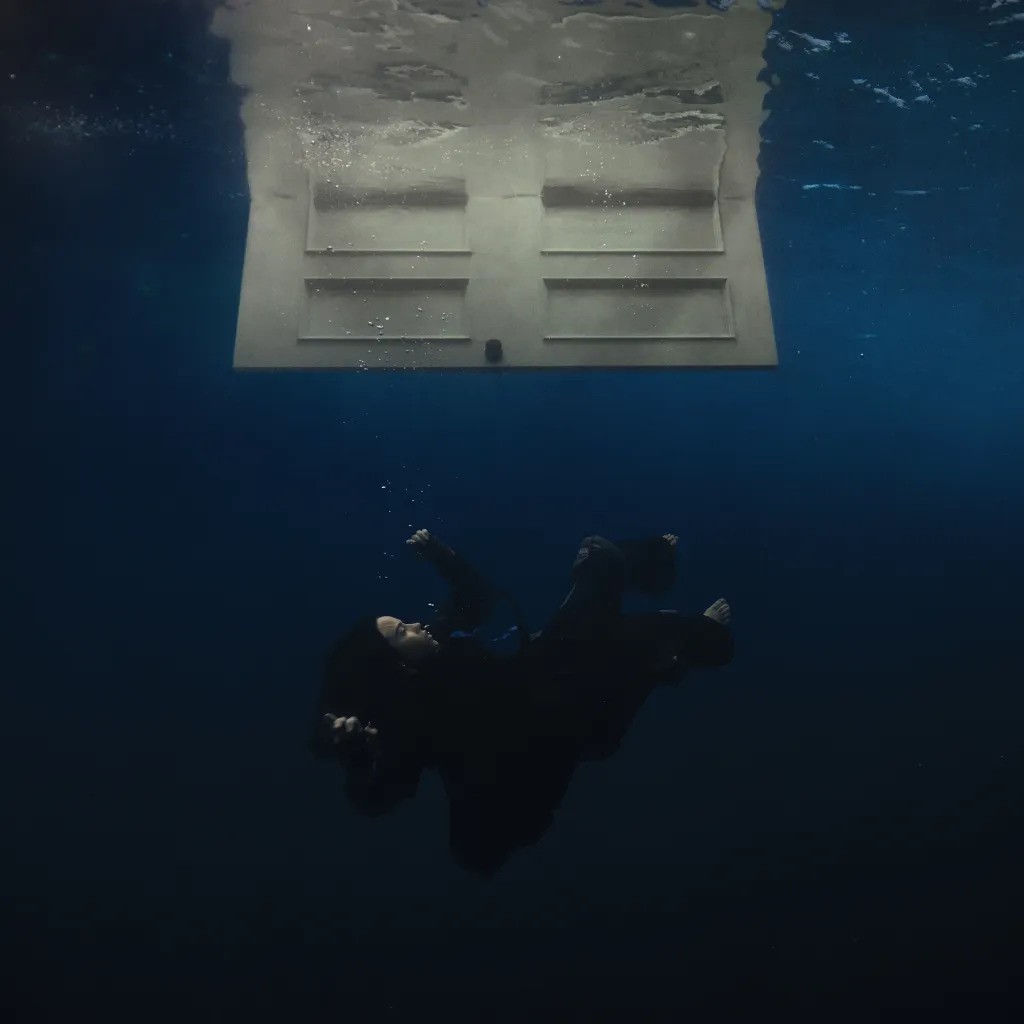

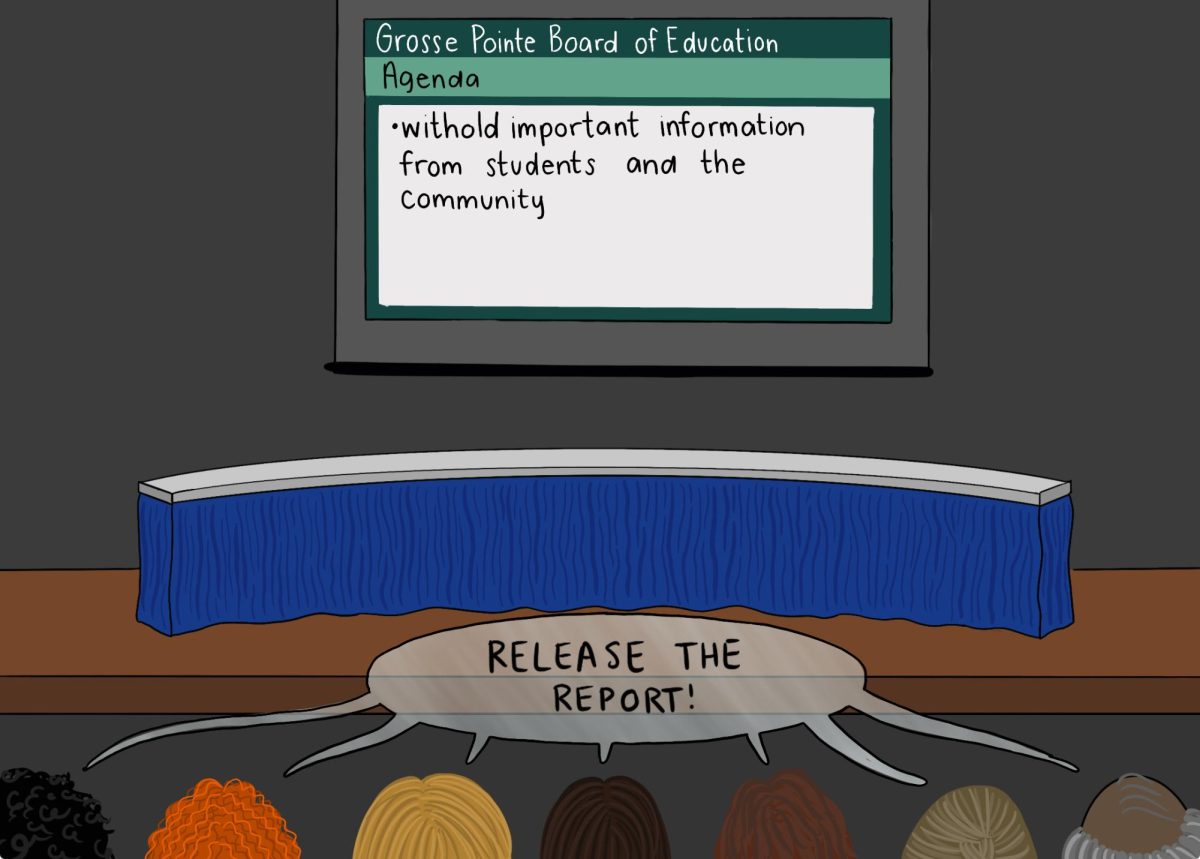

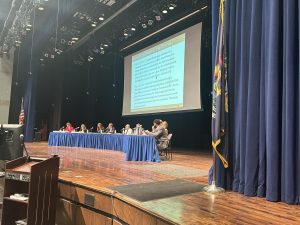

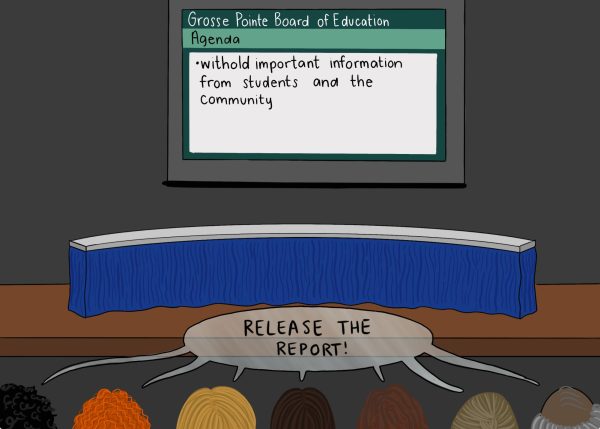

A board member’s anti-vaccination outburst at the August 23 Board of Education meeting followed by anti-mask protests in front of the school creates a blurred line between fact and fiction.

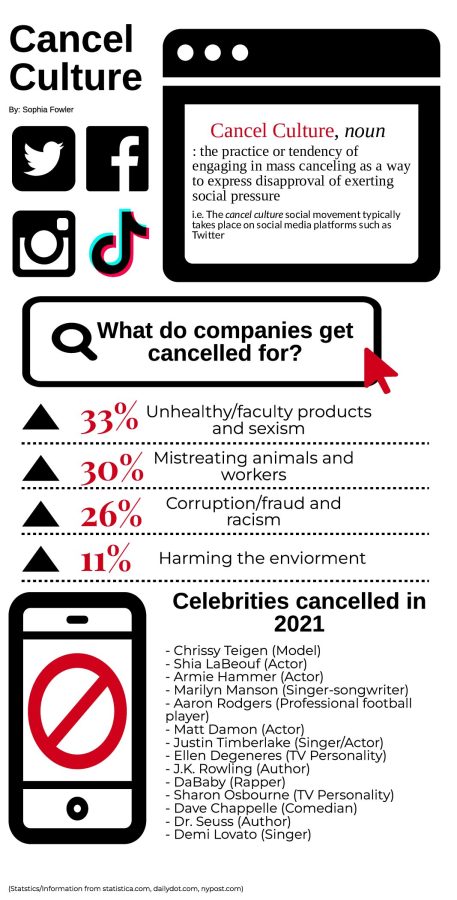

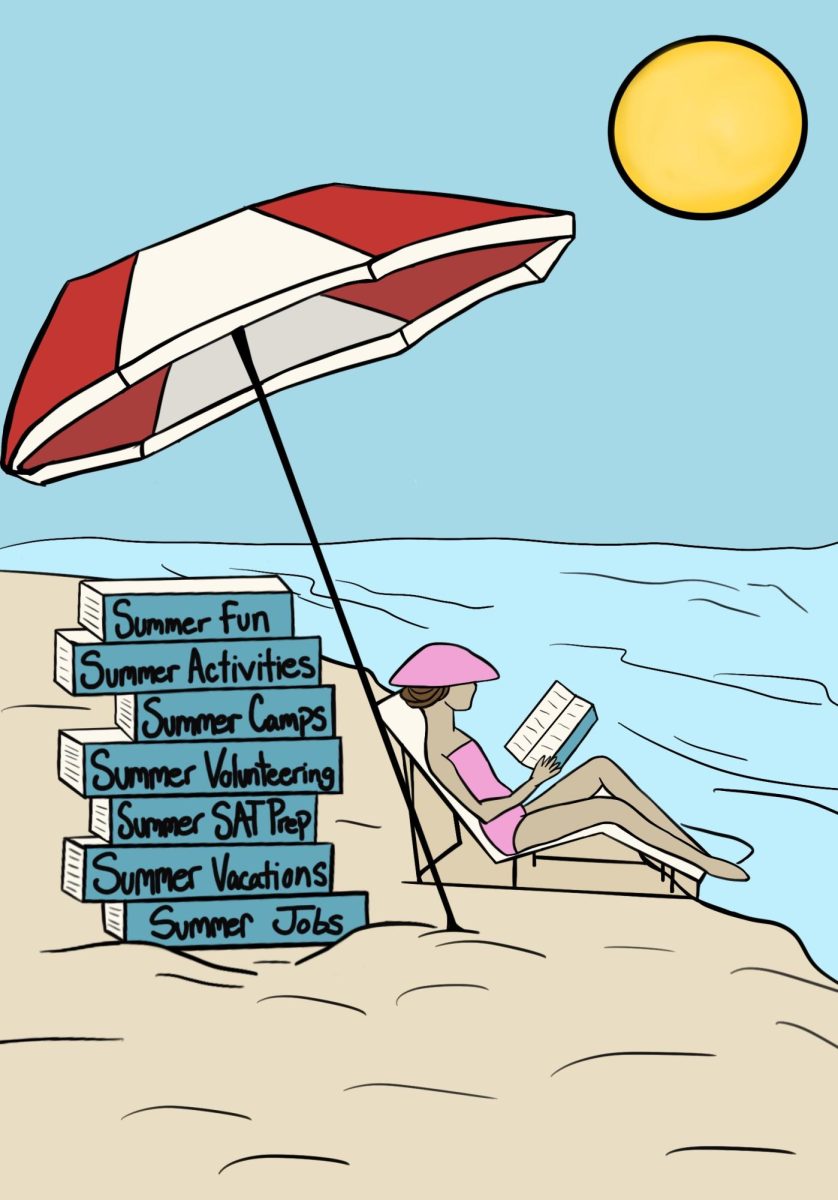

Though some websites, such as Instagram and Facebook, are now tracking and flagging false information, the sheer enormity of misinformation is almost impossible to regulate. This combined with a critical lack of media literacy allows misinformation to spread rampant.

“If everyone told you the earth is flat, you might start to believe it,” Madison Duff ’23 said. “Even if you are exposed to the truth, those false beliefs have already been ingrained in you.”

Duff said the main issue with unregulated misinformation is that it appears on many different platforms, often holding a political agenda. According to Duff, lies can take the form of “news” articles, conspiracy theories, and more.

“You can’t silence everyone,” Duff said. “Everyone has different perspectives, but it gets to a certain point where the line needs to be drawn. If it’s something harmless, it won’t have that much effect. But sometimes (the misinformation) gets to a certain point where there needs to be a place to draw the line.”

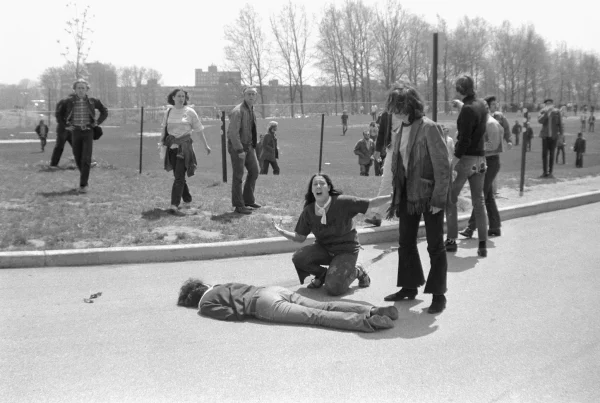

When these lies circulate around the internet, they can have substantial effects. Online discourse over a conspiracy can turn into very real anger, which can quickly transform into rallies, violence, protests and riots. The conspiracy theory of Pizzagate turned into a Comet Ping Pong shooting. Election fraud conspiracies turned into the Jan. 6 riots.

“Conspiracy theories create division not just on a local level but we have it on a national level too,” government teacher Michael Rennell said. “What they do is divide people. People who believe and buy into conspiracy theories are 100 percent in on it and then there are those who don’t. And that really creates animosity between the two groups. Truth in news and reporting is important and how we are ever going to get back to that is going to be interesting to see.”

On Sept. 17, several Grosse Pointe parents showed up at the corner of Fisher and Grosse Pointe Blvd., holding signs protesting the current Wayne County mask mandate. While she was walking onto campus, student Jane Johns said parents began to harass her about receiving the vaccine.

A woman at the protest compared the vaccine to HIV. She asked me if I would still take the vaccine if I knew I was going to be injected with HIV. She also said my ovaries would be messed up in the future.

— Jane Johns* Anonymous

These conspiracy theories can be seen at a higher level within the district. Board of Education member Lisa Papas, for instance, made claims in a Facebook post on Oct. 27, 2019, insinuating that John F. Kennedy Jr., who died in a plane crash in 1999, was still alive.

“There are a growing group of people who believe (JFK Jr.) is still alive,” Papas said in her post. “Given that he had to grow up witnessing the assassination of his father and uncle, it isn’t hard to believe that he might have arranged his own death and gone into witness protection. Imagine a Kennedy endorsing Trump. That would be a game-changer in politics.”

Papas has since discussed other conspiracy theories, including how the Center for Disease Control (CDC) is conspiring with Big Pharma. Some district parents, including Melissa Smith, are growing increasingly troubled by these posts.

“I think there should be some universal agreed-upon truths that exist, and when certain people cannot operate from that standpoint, those people should not be in positions of power,” Smith said. “It is upsetting to me when people do not operate from a standard of facts.”

Smith said she was upset that the parents who participated in the anti-mask protest actively pushed a false narrative onto the student body. However, she noted that there is a certain point at which energy is wasted trying to explain the truth.

“There are a certain number of people that will never be convinced, and it is at the point where we shouldn’t bother giving any of that oxygen,” Smith said. “Everyone understands what we have to do, and if you aren’t on that train by now, you will never be on it. It’s a feudal effort to try and convince people.”

According to Duff, to avoid falling down the rabbit hole of misinformation, people need to do their own research and know where their sources come from. Good sourcing and true scientific data has never been more essential than in the age of COVID-19.

“In regards to vaccination, I think people need to do their own research before they make the decision,” Duff said. “If you have genuine concerns for your health, that is understandable and valid. But if you just heard something crazy, that misinformation could potentially (kill) you.”

Rennell warned that, due to the massive increase in digital media consumption over the years, it is easier than ever to be consumed by misinformation.

“We have an information highway right in the palm of our hands,” Rennell said. “It used to be that you read the newspaper in the morning and watched the 5 p.m. news on television. Today everybody is just inundated with news, and it’s not always factual news. It’s just information overload.”

When searching on the internet, blindly trusting and believing in everything you read is an easy way to get caught in a conspiracy theory. Rennell said background information, and the sources and context from which that information is derived from, matters.

“I think that if something was founded in real evidence it wouldn’t be considered a conspiracy theory,” Rennell said. “If it has merit and it is found to be factual then it wouldn’t be considered a conspiracy theory. I think to be called a conspiracy theory, it pretty much has to be non-factual.”

Chris Cornwell • Oct 3, 2021 at 4:04 pm

Every time I worry about the future of our young people, I am reassured by outstanding perspective and thoughtful insight by impressive examples of our community. These two young ladies hit a home run and have shown us all that our children can be more responsible than some adults!