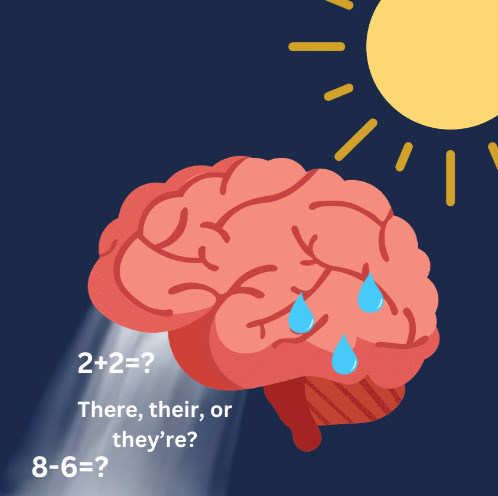

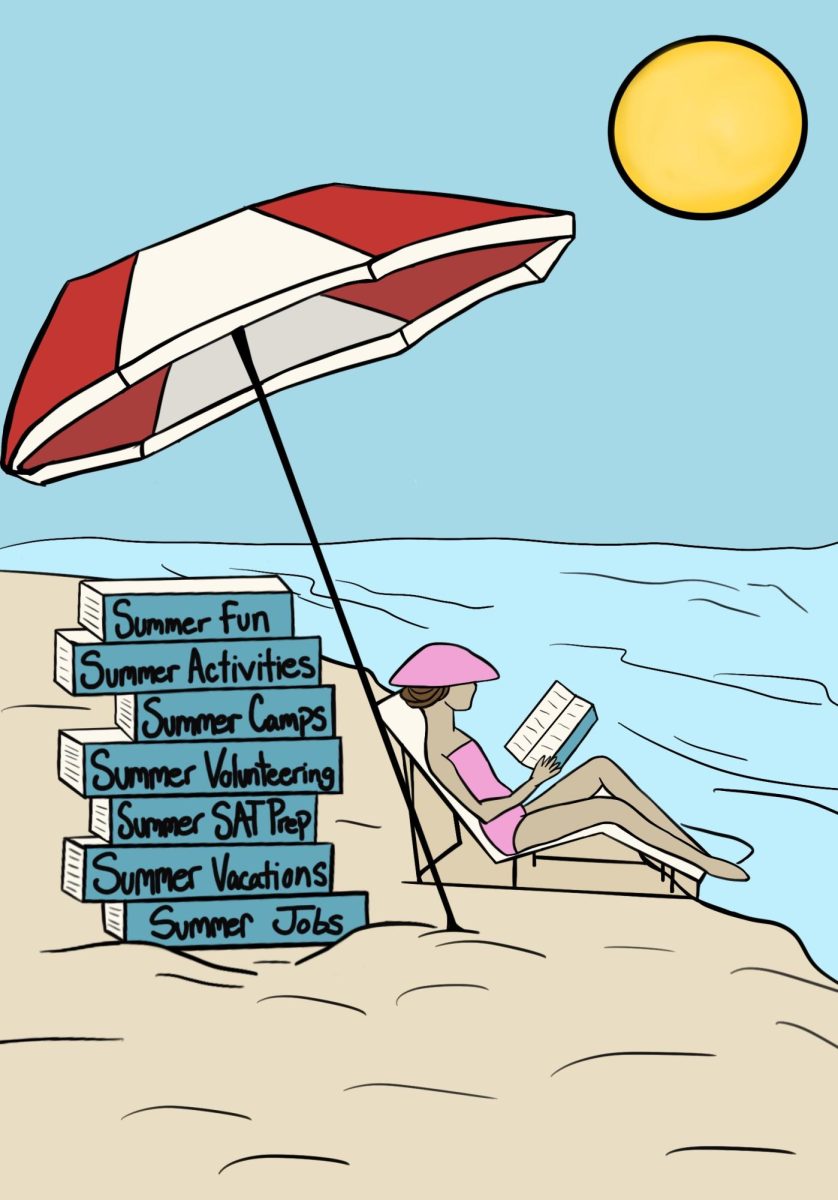

Stress pile up resulting in burn out

January 27, 2022

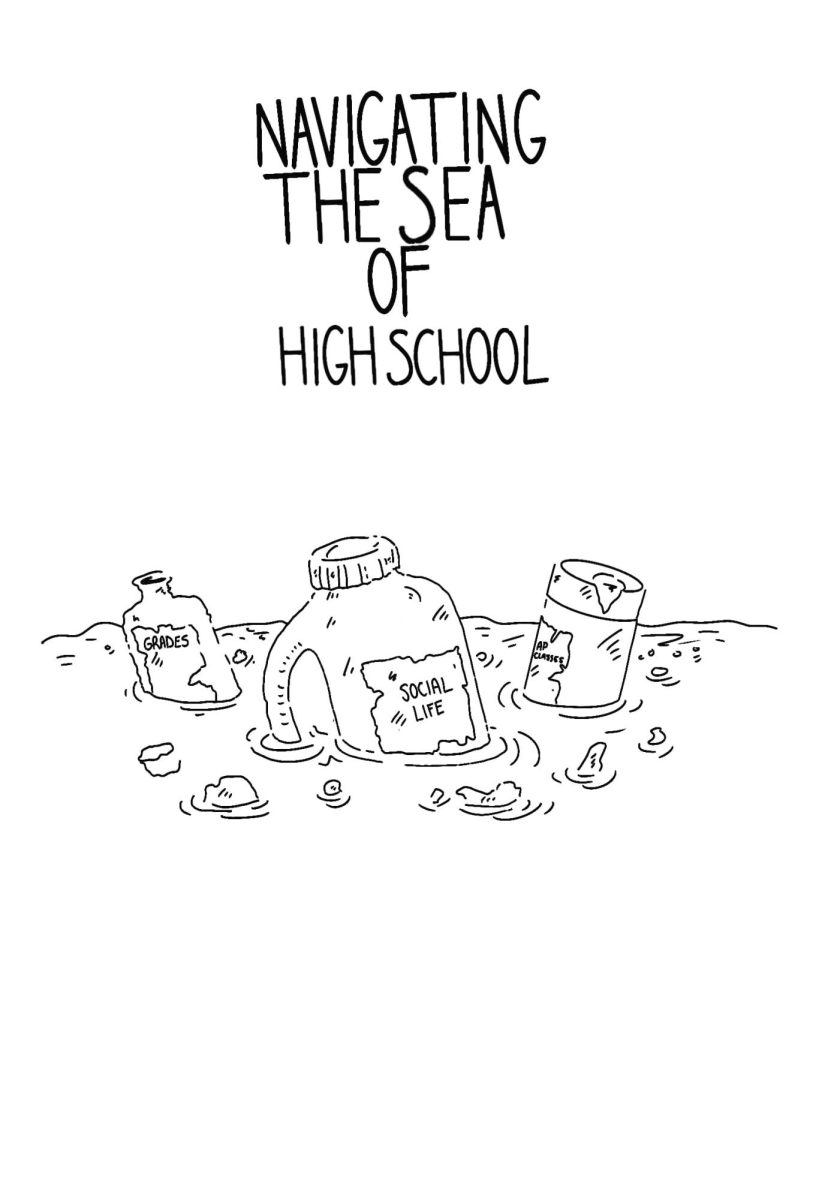

Considering this has been the first school year of normalcy in two years, there have been adjustments necessary for both students and teachers. The stress, especially with midterms and COVID outbreaks, have been piling up at an alarming rate, causing students and teachers to feel burnt out.

Teacher David Lubanski has been working with kids for 31-years and is currently long-term subbing for English teacher, Daniel Peck. Among the students that he has taught in these 30 years, he notices the students in recent years to have higher stress levels.

“This stress shows up through mannerisms in class,” Lubanski said. “I see a lot of worry about the topic of midterms and what will happen if COVID causes a student to miss the week before or the week of midterms.”

This stress felt by many students can also result in a more lethargic approach to both school and life. Rosalie Nykanen ’23 explains how her love for school has depleted over her high school years due to the stress.

“It’s hard to thoroughly enjoy what you’re learning in school when you’re running on five hours of sleep,” Nykanen said. “I would love it if I could go to bed earlier, but with school, sports, work and homework, it’s impossible to get eight hours of sleep a night and stay on top of my responsibilities.”

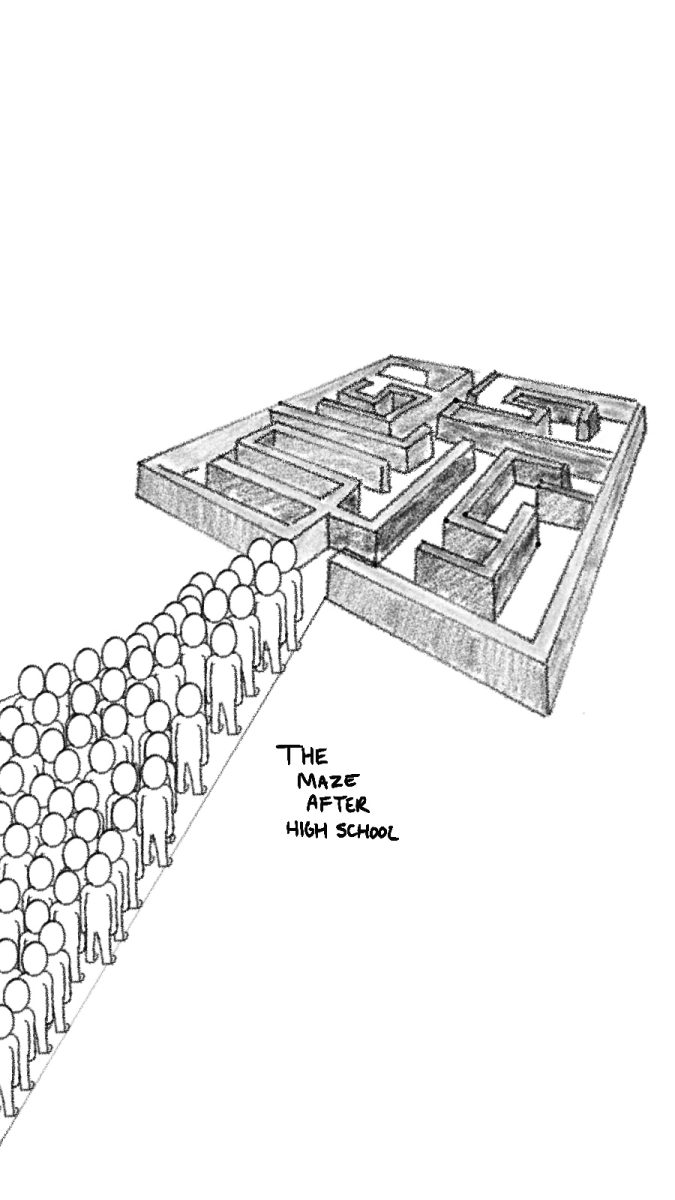

Another aspect that can be factored into underperformance is that the freshmen and sophomores have yet to have a full normal year of school. Seamus Doyle ’24 said this had a great effect on his learning.

“I haven’t had a full, normal year of school since seventh grade,” Doyle said. “It’s been three years since normalcy, so it’s expected that the underclassmen will have trouble remembering how to do school.”

Along with the stress already associated with midterms, students now have to worry about whether or not they’ll even be in attendance for the preparation of midterms, or the midterms themselves, Nykanen said.

“Not having COVID definitely puts me at an advantage compared to those who do have COVID,” Nykanen said. “I can physically be in school preparing with my teachers, while those at home can’t get as much out of the preparation, and I think that’s unfair.”

Doyle said the many students at home with COVID during this time have undergone more stress than they would have if they were in school, considering all the catch-up and makeup work they must complete from home.

“I feel like I’m more stressed now after finding out that I tested positive for COVID,” Doyle said. “It’s a ton of work trying to catch up with lessons in class, zoom recordings from last year, midterm preparation and homework from classes.”

Lubanski is able to use this stress among his students as a learning experience that has taught him a variety of valuable lessons that he is able to bring into the classroom.

“I look at my students as my sons and daughters and have a lot of empathy towards them,” Lubanski said. “I communicate a lot with them through class time and email in an attempt to nip the worry in the butt before it gets too stressful.”

A solution for this issue proposed by Lubanski is making the week four days, opposed to five days like it is now.

“As much as we want the normalcy of five days a week, I don’t think it’s healthy,” Lubanski said. “With all the stress, I think slowly getting ourselves back into the normal routine after all the time we missed would really help with the mental anguish felt by many.”