Blurred lines: With CTE injuries on the rise high school football is changing in America

December 19, 2017

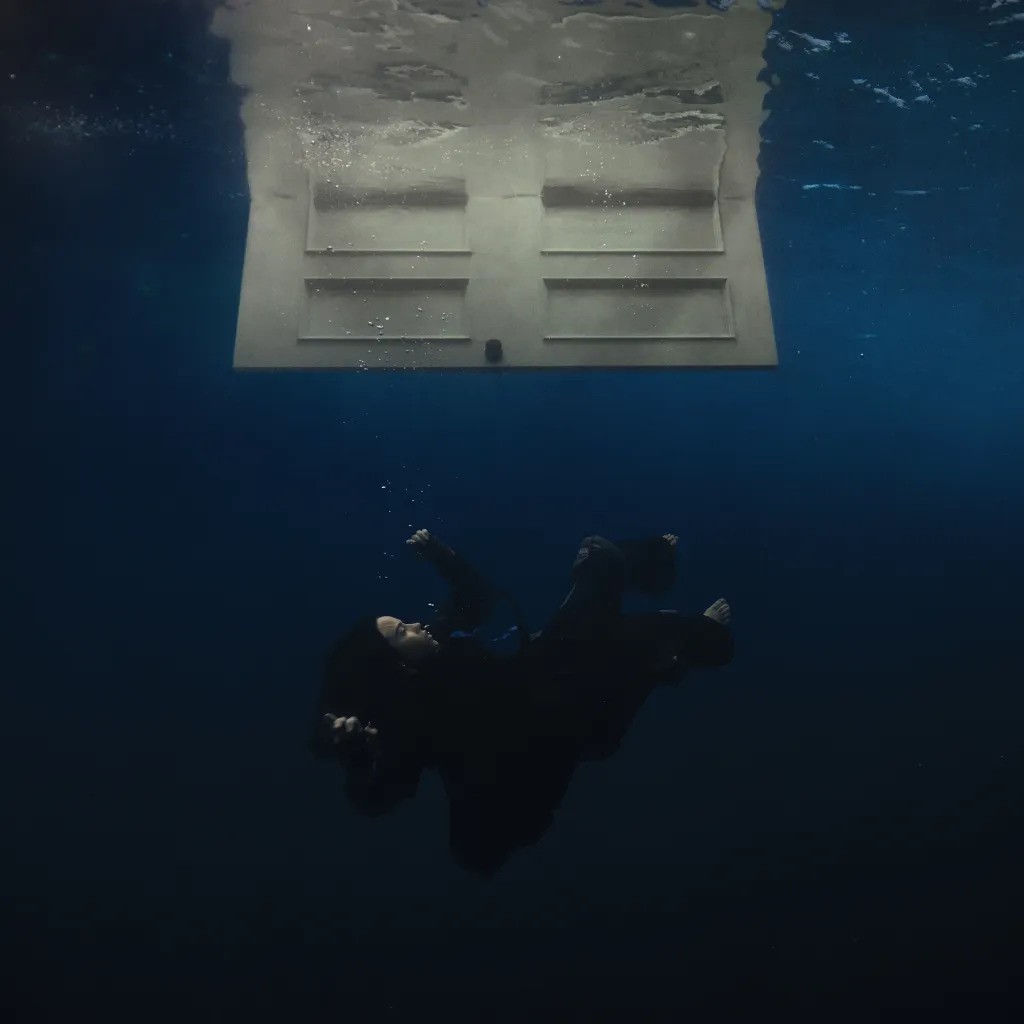

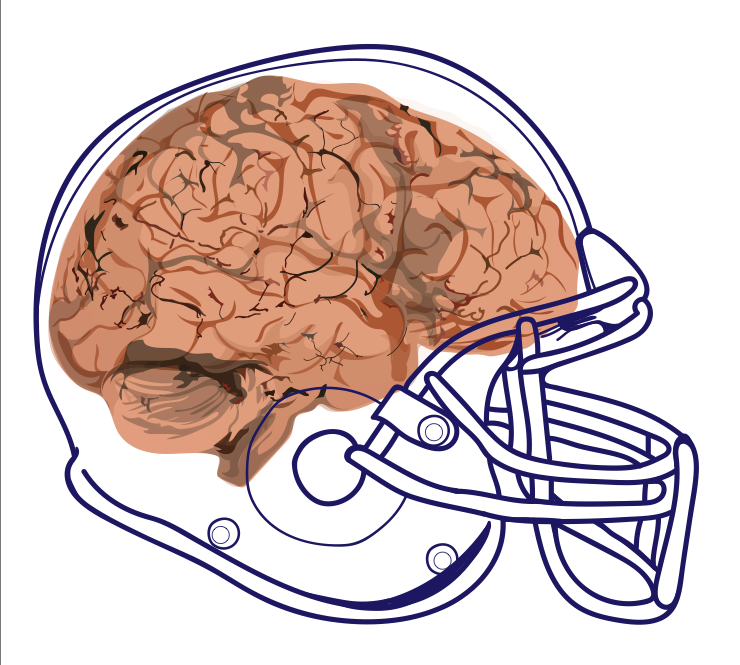

Sunday and Monday nights are denoted as football days. They are the nights when dads hush everyone to be quiet, yet break the silence when their team of choice inches closer to scoring a touchdown. They are the nights filled with the sounds of hitting pads and the release of adrenaline firing up fans across the country. But those hits come with consequences. Irreversible consequences.

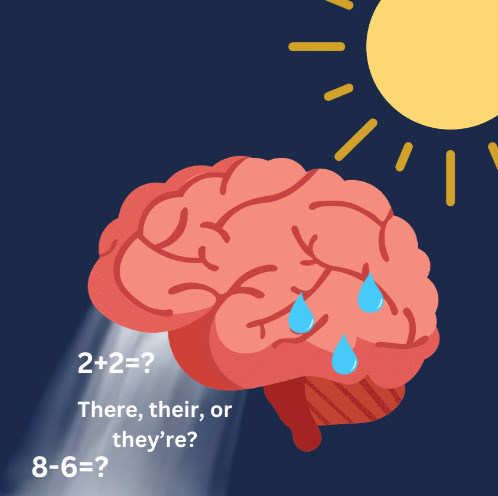

“The belief is that, in the long run, repeated concussions can and do lead to memory and/or cognitive impairment, behavioral changes, depression, etc.,” Dr. Pat Bishop, professor of kinesiology at the University of Waterloo, said. “There is also believed to be a link between repeated concussions and CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy), an extremely high buildup of tau protein in the brain that leads to nerve loss.”

Tau protein is a normal protein found in everyone’s brain, according to the DNA Learning Center. However, the buildup of this protein can result in the clumping and death of cells, leading to CTE. It is unknown what the cause of the buildup is.

In 2014, the American Medical Association began a study involving the examination of 111 brains of deceased National Football League (NFL) players. Of the 111, 110 were found to have CTE.

“CTE is a progressive neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s that usually affects three different domains,” Dr. Robert Cantu, clinical professor of neurosurgery and co-founder of the CTE Center at Boston University School of Medicine, said. “Cognitive, so that you have trouble with memory and trouble with attention span, insight and judgement. The second domain is mood and there, it’s primarily issues with depression or anxiety. Lastly, (it causes) difficulties with behavior. The one that is most common is lack of impulse control like explosive verbal and physical activity.”

But here’s the kicker: players don’t have to be in the NFL to get CTE. It is possible to develop it at the highschool level.

Dr. Cantu’s CTE Center examines the brains of deceased people that had experienced repetitive brain trauma, such as athletes and military personnel. According to Cantu, among the brains used for studying and research, 17 of them played no higher than the highschool level of football, and three of the 17 were found to have CTE.

There hasn’t been a documented cause-and-effect relationship between concussions and CTE, Dr. Michael Stuart, orthopedic surgery professor and chair of the Division of Sports Medicine at Mayo Clinic said. Although there isn’t solid evidence of this relation, it’s not a good idea to have multiple blows to the head because there will still be consequences, according to Stuart.

Along with not knowing the cause-and-effect relationship, your percent chance of getting it is unknown as well.

“The problem is, (we don’t know) how many people in high school, how many people in college, how many people in the NFL have CTE,” Cantu said.

With high school football accounting for 47 percent of all reported concussions, we need to strive to reduce the risk of concussion in the sport, according to Stuart.

“I think there are many benefits of team sport participation related to the physical, emotional and psychological growth of our young athletes–not to mention, sports are fun,” Stuart said. “I think we have to step back for a minute and make sure we are not over-emphasizing risk. So certainly, in the sport of football, there is risk: risk of concussion, risk of orthopedic injury, etc.. So my take has always been that we don’t want to get rid of sports, we want to make sports safer.”

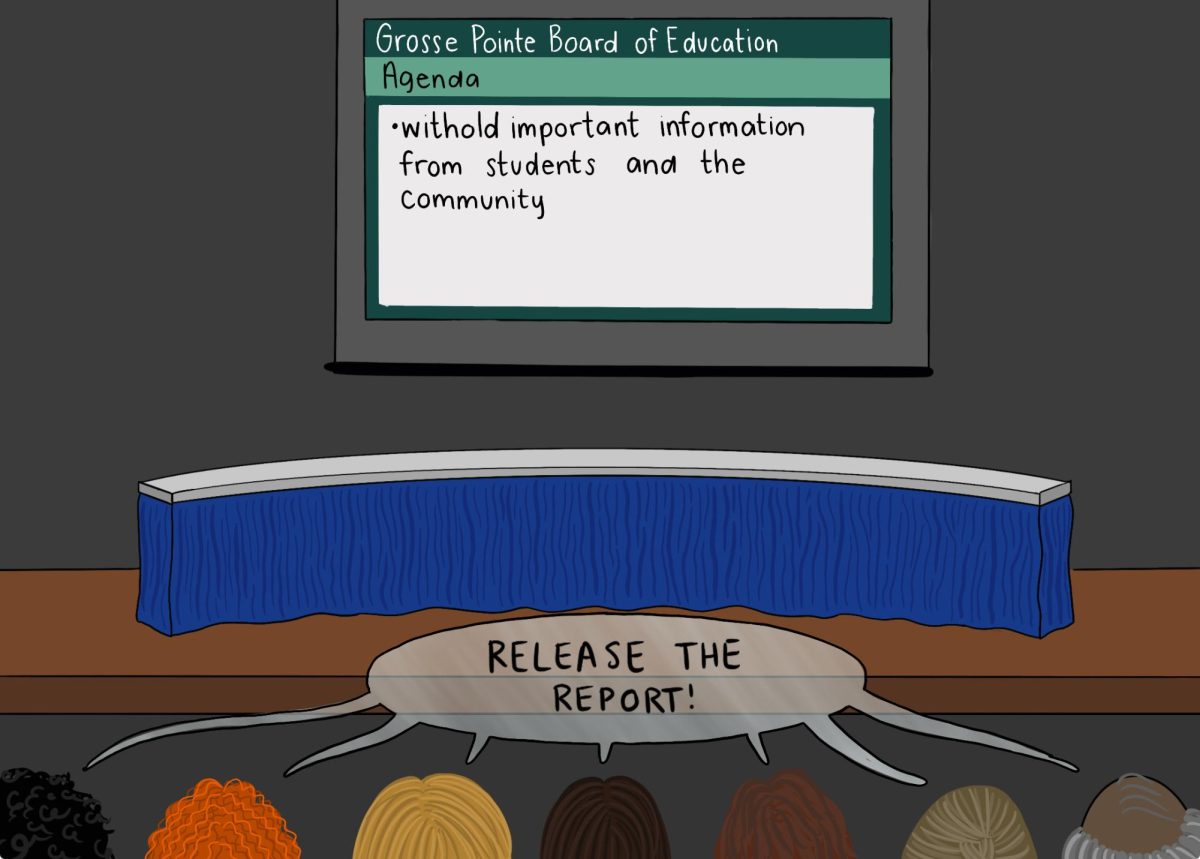

The Grosse Pointe South varsity football team focuses on how players tackle each other in order to reduce concussions.

“Every technique we teach are head-out-of-contact techniques,” Tim Brandon, head coach of the varsity football team, said. “The old days where they used to say, ‘lead with your face, lead with your head’ is gone. (Now) it’s completely head-out-of-contact. Plus, our equipment is better technologically than it used to be and again, the procedures and even the rules of the game have changed.”

Coaches of the Grosse Pointe South varsity football team preach tackling with your head up and not to hit with the top of your head, Alex Saurbier ’18 said.

According to Bishop, the most logical way to prevent concussions is to ban helmet-to-helmet contact.

“It is important to remember that a concussion is a brain injury, and, as such, is not “repairable” as are the other organs in the body,” Bishop said. “No two people have the same response to a concussion, so it manifests itself with different symptoms and different responses or reactions depending on the person.”

Bishop added that cognitive impairment can persist for a long time and can affect a student player’s ability to complete school work. Since a child’s brain is a developing one, it doesn’t react to injury in the same way an adult brain does.

The area of CTE research is not completely developed where there can be an understandable cause-and-effect relationship, Stuart said. As of 2009, only 49 cases of CTE have been studied and published, according to Cantu’s CTE Center. As a result, the disease is poorly understood.

“There is certainly a chance, and it is a concern, that repetitive blows to the head and multiple concussions with participation in a sport like football could conceivably lead to these progressive neurodegenerative diseases in the future, like CTE. However, we don’t understand it yet because there’s probably multiple other factors,” Stuart said. “For example, there is probably some individual susceptibility based on genetics that may predispose athletes.”

There’s new research being conducted in order to connect these dots, according to Bishop.

“There have been several recent developments in concussion research,” Bishop said. “Some centers are looking for blood markers for concussions, some are looking for better diagnostics in the form of fMRIs and diffusion tensor imaging, and some are looking for better treatment and return to play/learn protocols.”

Longitudinal research is being conducted where athletes are followed and monitored over time, Stuart added. Stuart hopes this will result in diagnostic measures for the living since CTE is a disease diagnosed post mortem.

Although CTE has been found in many athletes’ brains, it’s not just unique to sports, according to Cantu.

“The highest risk factor (for CTE) is exposure,” Cantu said. “CTE is very much like cigarette smoking–if you play football or have repetitive head injuries that doesn’t mean you are going to get CTE. Not everyone gets it, but it is dose-related, so the more head hits you take over a longer period of time, the greater chance you have of getting CTE.”

With the field being quite unknown, Stuart warrants that we shouldn’t be hasty when pointing fingers as to what the true cause is.

“There could be other mitigating factors that would contribute that we don’t understand yet,” Stuart said. “Many of the pro athletes who have been diagnosed in an autopsy with CTE had a lot of other issues. They had emotional issues, psychiatric issues, drug and alcohol abuse, but did the concussions or traumatic brain injury or the permanent brain damage cause them to have physiatric illness or lead them to drug and alcohol abuse, or were they unrelated factors? I think we have to be careful about assigning risk to sports participation if somebody has issues later in life.”

It is important to keep in mind that playing through a concussion will do more harm than good, according to Bishop.

“There are several risks related to playing through a concussion, including loss of awareness, loss of cognitive ability, etc., which can place a player in harm’s way,” Bishop said. “The most important concern, though, is that of the player receiving another head blow while the brain is already injured, and this can have disastrous consequences.”

Brandon relays the same message to his players.

“First of all, we train the athletes to know the symptoms, so them knowing to self-report is a huge aspect of it,” Brandon said. “Sometimes it might be a normal tackle where you get jarred, so if we observe any kind of behavior in that athlete we can send them to Rochelle (South athletic trainer); the officials in the game have the authority to notify us and then we send them to Rochelle. There’s a whole process which was built around the fact that we want our athletes to be safe.”

With all the risks and concerns that football and even other sports pose, it’s important to keep in mind the benefits of them, Stuart said.

“I would say, as an orthopedic surgeon, sports medicine specialist and father of three former NHL players and now a grandfather, that I am very concerned about concussions in sports. But, again, I am driven to try and make sports safer and it’s a multifactorial and a very challenging solution, and it has to do with prevention. It has to do with more accurate diagnosis, it has to do with better treatment and it has to do with probably understanding risk better so that we can continue to reap the rewards of individual and team sports without trying to eliminate them,” Stuart said. “We can’t lose sight of the fact there are a lot of benefits to sports and I really think we ought to keep that in mind.”