Growing up I had always known that my Grandma, or as I call her, Nana, was a “hippie”. That word was thrown around in my family while trying to describe my Nana’s free spirit: how she dressed, the music she loved, and her overall optimism that I still see in her today. As I have grown older, I’ve realized that my Nana was a product of history, not just a “peace” preaching “hippie”.

Graduating Magnificat High School in Rocky River, OH, in 1964, an all girls private catholic school, Ann Roeder, my Nana, attended a local arts school on scholarship. After two semesters she enrolled in Kent State University in 1968, after taking a year off from school working three jobs to meet tuition for Kent. Stepping on campus in 1967, she was excited to find her independence from her 7 siblings back in North Olmsted, OH.

“Going to Kent was really nice, but this was also when the Vietnam War was heating up.” Roeder said.

Kent State students, like college students across the country, had been holding peaceful anti-war protests since early 1964. But a major turning point in these protests happened after President Nixon’s announcement of the invasion of Cambodia, which changed the nature of the protests.

My Nana was in her Second year at KSU, studying English and Art, when the protests escalated. She had attended countless anti-war protests while at Kent, including the Saturday May 2, 1970 protest on campus when the Reserve Officer’ Training Corps (ROTC) building was burnt down, but she only partook in peaceful protests. The protests in the days leading up May 4, 1970 would prompt the National Guard to be called in by then Governor Jim Rhodes.

“I remember the National Guard showing up,” Roeder said. “They walked through the crowd that the ROTC building was, just burnt down. It made people nervous (The National Guard), that’s for sure because it was an arm of the military. But I think the level of commitment against that war was really strong, so I think it outweighed all that fear.”

At this time, protesting the Vietnam War was incredibly controversial. Many of these college students had seen friends or family members drafted off to the war, or were at risk of getting drafted themselves, making a war taking place across the globe hit close to home.

“Many Americans saw the protests as betraying the country and being unpatriotic when it’s not unpatriotic to criticize your country at all,” Roeder said. “Many people thought that America could never do any wrong or choose a wrong war, you know. Vietnam was kind of an eye opener for the country.”

After a weekend of protests, on Monday May 4, 1970, a scheduled protest was held in front of Taylor Hall in the heart of KSU’s main campus. As classes were still set to be held, the National Guard was still present on campus.

“On Monday I was getting ready to go to class and the phone rang, and it was my mother.” Roeder said.

I am incredibly lucky to have known my Great Grandma, my Nana’s mom, who was notorious in the family for keeping people on the phone. Her talkative and high spirit personality was passed down to all of her 8 children. Little did my Nana know at the time of the phone ringing, that my Great Grandmother’s call may have saved her life.

“I thought, ‘what a bad time to call’, I was rushing to get to class on time,” Roeder said. “I was on the phone for a while but eventually I told her I was going to be late for class.”

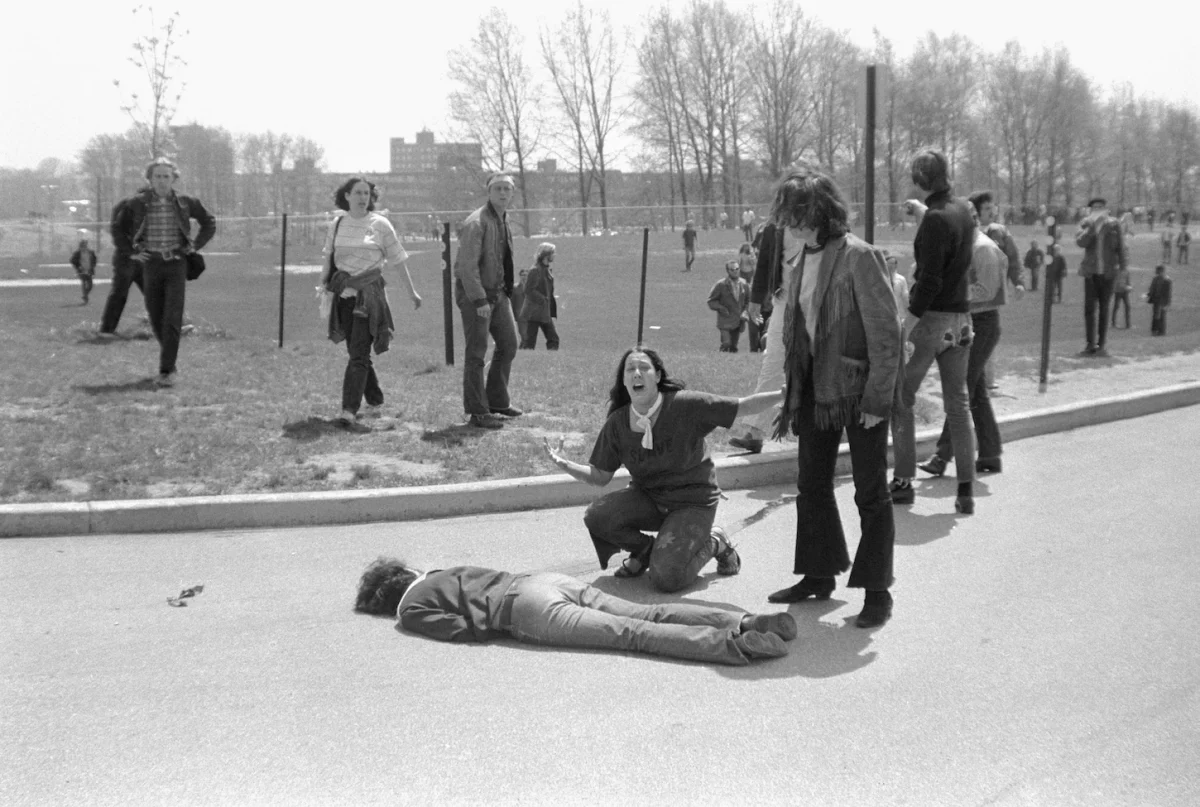

On Monday May 4, 1970, a group of students gathered in a common area on campus around 11 AM, culminating in over 3,000 protesters by 12 PM. Of these protesters most were students, but professors at the university also participated. After almost an hour and a half of the protest, at 12:24 PM the National Guard Opened fire at the crowd, fatally shooting 4 protesters.

“It was a horrible day,” Roeder said. “We were all in a state of total, total shock. I don’t think anyone could have predicted that they were going to shoot into the crowd like that. I mean, there could have been a blood bath if they had all opened fire. Everybody was just in a state that I can’t even describe what it’s like.”

As my Nana was walking to class, she walked into the common area where the protest was happening, hearing the shots fire.

“I heard what sounded like firecrackers, I didn’t know they were shots,” Roeder said. “When I got over the hill everybody was running and screaming. It was just total chaos. And when the shots stopped we were in total shock and realized there were actual dead bodies.”

As the day was unfolding after the incident, campus was shut down and a curfew was put in place to prevent more protests. Marshall Law, setting a curfew,

was declared on campus, resulting in the arrest of hundreds of students due to many people gathering in small groups, which is illegal under Marshall Law. Many students decided to leave campus, including my Nana.

“I had a really old Volkswagen and I packed up my car, said goodbye to my roommates, made sure rent was paid and left.” Roeder said.

My Nana left for California later that spring, never coming back to Kent State to finish her education. Classes at KSU did not come back for class until the start of the fall semester.

The KSU shootings were a pivotal moment in the Vietnam War protests. It displayed the amount of power youth protesters had along with how the government decided to react to the national protests.

“The time was such a volatile time in this country.” Roeder said.