Divided Detroit

December 15, 2021

Toyia Watts calls it a tsunami.

A lifetime Detroit resident of the Islandview neighborhood and president of the Charlevoix Village Association (CVA), Watts has witnessed the effects of gentrification steadily increase over the past 20 years. She felt it necessary for her survival to take action.

“I came up with CVA in the early 2000s,” Watts said. “We educate people on what’s going on in the neighborhood. Detroit told us we were part of the ‘urban transformation’ framework, but we’re not. So we speak out, otherwise we don’t get a seat at the table– no way, shape or form.”

Per definition, gentrification is a term for the arrival of wealthier people in an existing urban district, a related increase in rent and property values, and changes in the district’s character and culture. It is negatively associated with the social and economic marginalization of existing residents.

Wayne State University Coordinator for Digital Publishing Joshua Neds-Fox said the rate of gentrification in Detroit is relatively low, pointing to evidence from a 2019 University of Chicago paper which states that two of 276 neighborhoods were found to be gentrifying between 2000 and 2010. However, the research cited precedes Detroit’s bankruptcy, Mayor Mike Duggan’s election and the impact of businessman Dan Gilbert’s billions of investments in Detroit over the past decade.

“The issue is polarizing because it touches on deep emotional responses to issues of race and class,” Neds-Fox said. “It would be hard to argue that white suburbanites aren’t moving into the city, or that property values aren’t rising in Downtown and Midtown, but determining whether this gentrification is harmful or restorative is an area of fierce debate that hinges on subjective ideas of what constitutes harm and what constitutes restoration.”

When the City of Detroit began the planning process to revitalize the Islandview neighborhood in 2017, CVA developed a list of 11 demands, designed “so that long-term residents (could) benefit from redevelopment in Detroit.” One of them pushes for investing in schools, libraries and tech centers to bring back young families.

“The young generation isn’t in the inner city of Detroit anymore,” Watts said. “I have a school right down the street– Marcus Garvey Academy– and they have to bus the kids in from Warren, Roseville and Eastpointe. I don’t have kids running up and down the street. And I have a school right here. Something’s missing.”

Intended to fill such gaps are private organizations like Little Free Libraries®, the nonprofit dedicated to “expanding book access for all” through individually-purchased tiny book boxes. While at first these companies may seem laudable in their efforts to help neighborhoods attract families, Neds-Fox warns of their underlying performative nature.

“There is a lot of analysis available that casts a skeptical eye on the project,” Neds-Fox said. “(Little Free Libraries®) are not technically libraries. In their unstructured privatization and individualization of the cooperative good, they work against community enhancement.”

Former Detroit resident Kayla Moxley ’22 has also recognized changes within the city. According to Moxley, gentrification “affects the culture of the city because (new people move in) with no type of cultural awareness or sensitivity, causing other problems within the community.”

“When I was Downtown a week ago, there was so much going on, and the city looked so beautiful at the moment because of all of the Christmas lights,” Moxley said. “But when I was driving home, the lights started to fade and the city started to get darker and all I saw were abandoned buildings, streets that had no houses at all and people just struggling to survive. Those people are the heart of Detroit– not Downtown.”

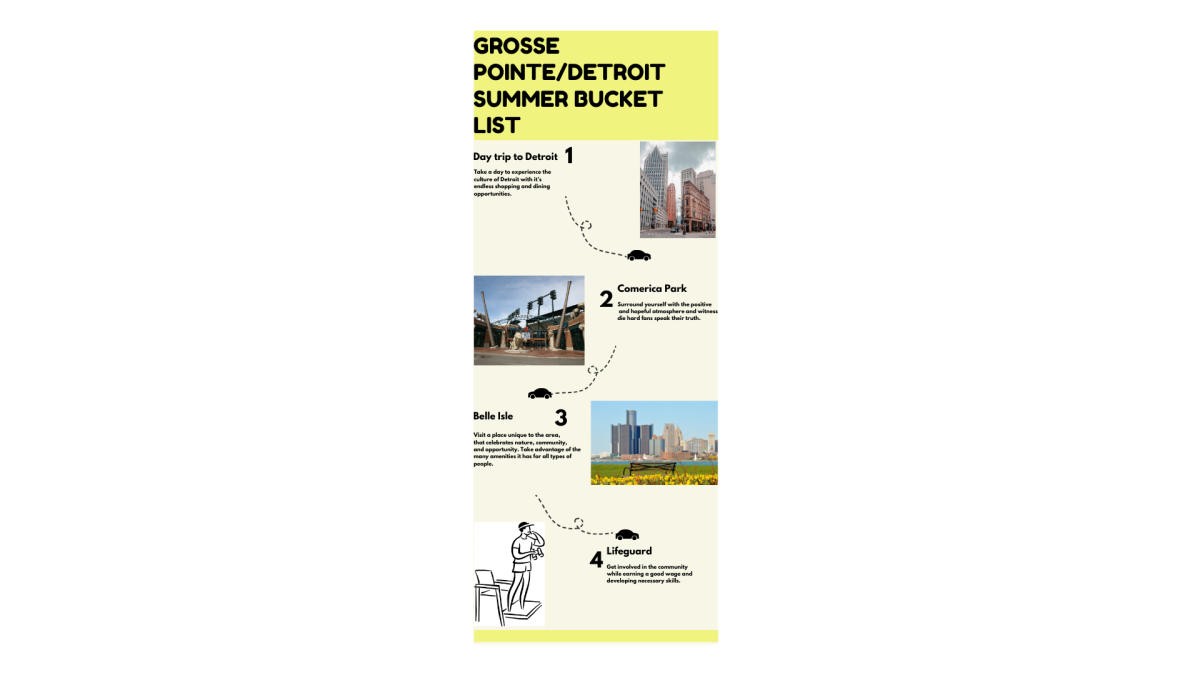

Beyond the borders of Detroit, gentrification also impacts relationships amongst Metro Detroit residencies, according to sociology teacher Kendra Caralis. Notably, Caralis said fear-mongering within Grosse Pointe fuels the ideology that certain areas of Detroit, typically un-gentrified areas, are unsafe– furthering the divide between the two cities.

“Because Grosse Pointe is predominantly white, and Detroit is predominantly Black, (there is) a huge wedge between them,” Caralis said. “The racial prejudice that can exist within the Pointes (is a result) of the assumptions that are made, which are not accurate.”

To her point, Caralis said white saviorism doesn’t appear to be contributing to the gentrification of Detroit, “because if that were the case, (people) would be trying to stay and help (the city).” Moxley agreed with this sentiment, pointing to the lack of empathy people seem to hold for the residents of the city.

“The biggest contributor to the gentrification of the city is most definitely greed,” Moxley said. “One little section of the city gets to thrive because outsiders can afford to live in nice, newly-constructed buildings – buildings built by people living in decaying ones.”

Wayne State postdoctoral fellow and CVA volunteer Allison Laskey studies how working class Black residents assert demands for equitable development and racial justice in Detroit. She noted there are key mechanisms siphoning resources out of neighborhoods like Islandview and into neighborhoods like Grosse Pointe.

“Segregation is a conscious policy,” Laskey said. “The dividing line between Detroit and Grosse Pointe– that’s a really strong boundary. It seems kind of arbitrary, but it was put into place through conscious policies that are consciously maintained. It’s a question of power.”

Although there is such a stark divide between the cities, Caralis believes Grosse Pointers have a unique opportunity to use their privilege to uplift their neighbors in Detroit.

“It’s a tough thing to be in an area of privilege, and not see privilege as a dirty word,” Caralis said. “(You want) to lift up other people without looking or feeling like you’re the bad person, like there’s something wrong. There’s nothing wrong with the privilege we have (in Grosse Pointe), but it needs to be used to help those that don’t have that.”

Detroit resident and South counselor Nicholas Bernbeck, who has experienced gentrification firsthand with the Ambassador Bridge, agreed with Caralis. He said it is fundamental to be a considerate citizen in order to preserve the culture of the area and limit any potential gentrification.

“It’s fine to move somewhere, but if you’re not trying to understand your neighbors, you’re not being a great neighbor or community member,” Bernbeck said. “I would encourage (anyone moving to Detroit) to get an understanding of where they’re living. How did it get the way that it is? Why does the city look the way that it does?”

Laskey said a critical part of understanding and preventing gentrification is taking residents’ needs into account. Many are open to the idea of revitalization, she said, but they often end up being the most impacted with the least amount of information about such plans.

“This conversation often turns into a question of pro-development or not, but the residents have been asking for development in the neighborhood for years,” Laskey said. “It’s just that when resources finally arrived, they didn’t meet the needs of what people were asking for. A basis of this neighborhood is their generosity, but it’s difficult to be generous when you’re being forced out in the process.”