Beyond the Pointes: Modern Segregation through Environmental Racism

April 25, 2021

While communities like Grosse Pointe thrive, neighboring communities struggle to have their basic environmental and human rights met. Oftentimes, these communities are unable to breathe clean air, drink clean water and live in safe neighborhoods.

Zip code 48217— an area of Southwest Detroit— has been identified as the most polluted zip code in Michigan. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considers the area a non-attainment zone because of dangerous levels of sulfur dioxide, a known contributor to asthma and ozone that exceeds what’s permitted under the Clean Air Act.

Catherine Diggs already knows this. The Manager of Programs and Outreach of Detroit nonprofit Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, Diggs said the environmental justice movement in Detroit and its surrounding communities is one born out of necessity.

Systemic Racism

Barbra Carson, the aunt of Hunter Moreland ’22, has lived in Flint, Michigan for 71 years. She noted the effects of the 2014 Flint water crisis are still present seven years later.

“People are still afraid to drink the water in Flint because there was no honesty during (the Flint water crisis),” Carson said. “There is a lack of trust between the people and city officials because they have never asked nor communicated with the public about what they were doing.”

As a result of this disconnect, Carson said it is difficult to trust the government to protect the interests of Black people— this distrust extends into the Flint community.

“The relationship between Black people and the government is something that is insincere because the government has only ever cared about themselves,” Carson said. “(Flint) city officials are trying to cover their tracks instead of trying to help people.”

But Flint, while nationally publicized, is only one example of the severe effects of environmental racism. The Center for Disease Control cites systemic inequities in social determinants of health as a reason why minority groups are more likely to have increased COVID-19 disease severity. Diggs called the link between environmental racism and the deadly impacts of COVID-19 on Black and Brown communities “inseparable”.

“When people who live in historically polluted neighborhoods have an illness like COVID-19 that affects the lungs, it becomes obvious how much damage corporations are doing to these neighborhoods and the people who live there,” Diggs said. “People start dropping like flies. COVID-19 really brought that realization to light for (many people).”

University of Michigan sustainability professor Kyle Whyte, who is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and sits on the Biden/Harris administration’s Environmental Justice Advisory Council, said corporations often take advantage of Indigenous communities who have been denied the right to organize.

“Indigenous people don’t really have an option to define what is safe in their community because we have been denied the capacity to operate as sovereigns,” Whyte said. “Tribes in Michigan have recently won some victories, like the stall on the Line 5 pipeline, but it’s very taxing on communities to have to fight those battles all the time.”

According to Diggs, money and the ability to organize play a significant role in where corporations choose to build refineries and plants in Detroit and the rest of the country. The placement of these buildings, she said, doesn’t happen by mistake.

“They would never open Marathon Oil Refinery in Grosse Pointe,” Diggs said. “You have money; your voices are heard more loudly. They know they’d never get a permit in Grosse Pointe, but they can get a permit in Southwest Detroit. They know undocumented residents are scared to go to hearings because they might get deported. It’s very strategic.”

Education

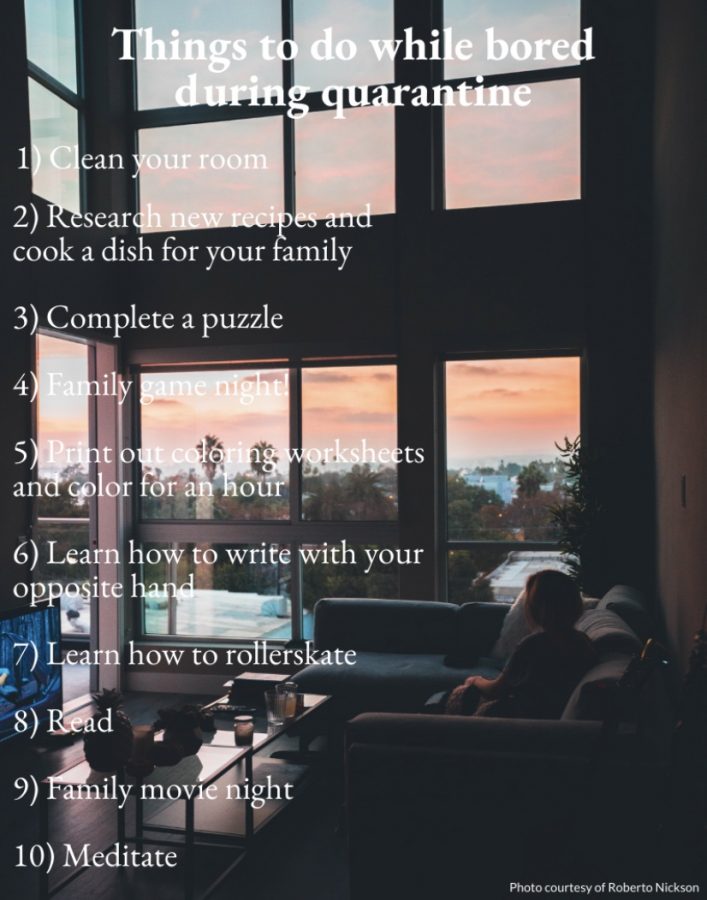

In light of this, Diggs said education is the first step toward expanding conservations around environmental racism. People in affluent communities must become aware of how historic environmental racism affects food, housing and economic insecurity in communities of color, according to Diggs.

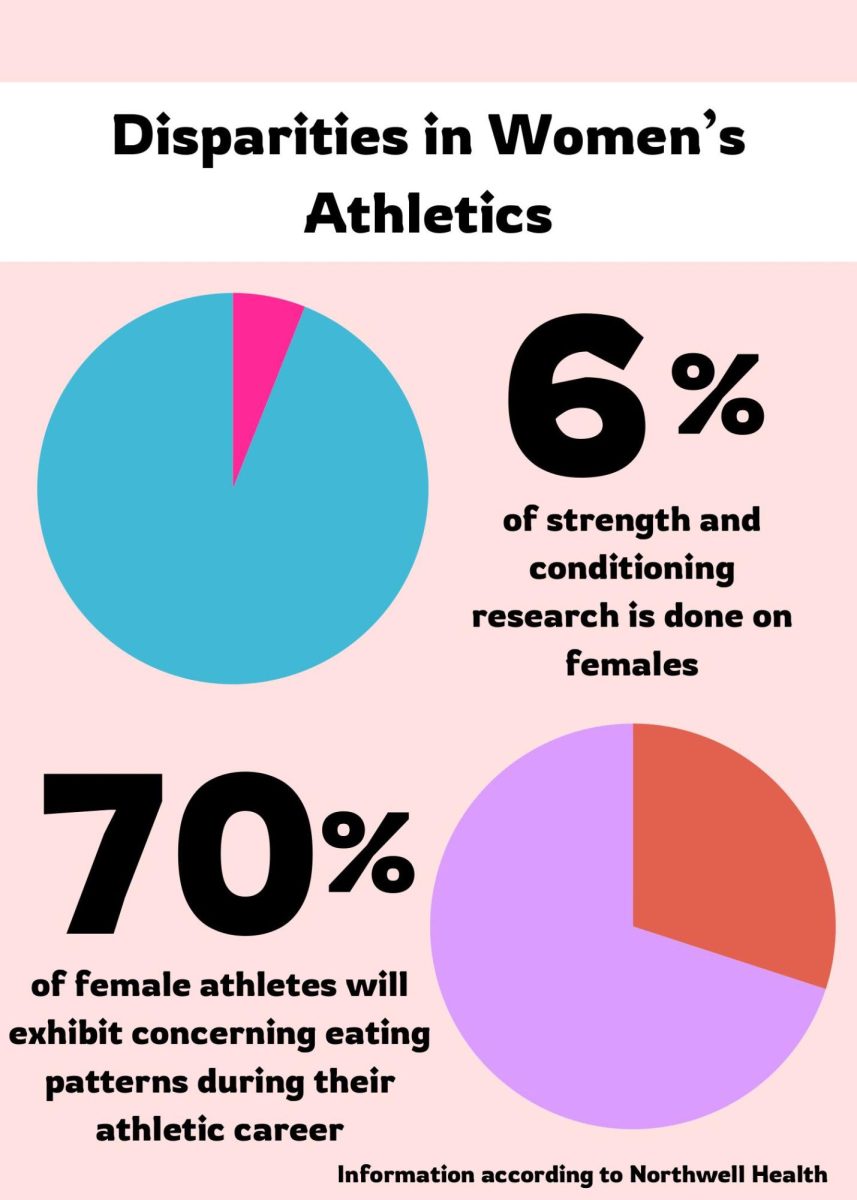

Within environmental education, Save the Lakes president Bridget Clark ’21 said more visibility is necessary in the environmental justice movement— a claim substantiated by a 2014 University of Michigan study that stated “the dominant culture of (environmental) organizations is alienating to ethnic minorities, the poor, the LGBTQ+ community and others outside the mainstream.”

“Environmental activists (often) overlook other cultures when they’re trying to make a change,” Clark said. “For example, veganism is promoted as a great way to reduce your carbon footprint, but it has been advertised as if eating meat is a very bad thing. (In reality, Indigenous) cultures source meat sustainably.”

Whyte said the absence of policies dedicated to anti-racism within environmental groups can be somewhat attributed to misinformation surrounding Indigenous history. A 2015 report by researchers at Pennsylvania State University found 87 percent of content taught about Indigenous people includes only pre-1900 context, resulting in a “painfully one-sided” curriculum, according to Whyte.

“People are not supportive of our goals and well-being,” Whyte said. “Notice in almost any educational system, there’s almost no curriculum on Indigenous culture. A lot of Americans grow up not knowing anything about the fact that prior to the formation of the United States, there were generations of Indigenous people living here.”

Carson also pointed to the lack of education on the adversities of minorities in American schools, saying the main thing that needs to change in order to combat environmental racism is people.

“People are the prime reason there is environmental racism in the first place,” Carson said. “We need to teach people how to care about our environment because right now all we’re doing is living in a trash can— we have the power to pick up one piece of trash and it can make a difference.”

Moving Forward

However, educating people is only one part of the equation. Moving forward requires reflective change, and in order to make a lasting impact on American culture, environmental policy must be reformed to reflect all voices, according to Diggs.

“Environmental racism (can be dismantled at) a larger scale when leaders have experience in environmental justice,” Diggs said. “Nothing would change if communities didn’t organize— corporate interests would always take over without pushback. It’s when oppressed communities fight back, which they have and continue to do, that things begin to change.”

Whyte seconded Diggs, arguing the course of redefining environmental policy should be at the discretion of people of color. Alongside the Biden/Harris administration, Whyte is working to assess investment in renewable energy and sustainable infrastructure, updates to Executive Order 12898 and more. In regard to Indigenous communities, Whyte said tribes must be given the opportunity to interact with the policy-making process.

“(We need) to find ways to strengthen the voices of Indigenous people and people of color so they can determine their own approaches to respecting the environment and to transitioning into a zero carbon energy system,” Whyte said. “They must have a chance to consent to activities that threaten their environment. They get to determine what safe enough means.”

Diggs said the most important thing to take away from the environmental justice movement is that it is intrinsically interconnected with the broader social justice movement. Justice for our planet and justice for all people are two profound conversations happening simultaneously, but often in different rooms.

“Communities of color living by polluting facilities has a lot to do with deep systemic racism,” Diggs said. “The result of that is massive public health issues combined with scarce economic and educational opportunities. It’s an endless cycle of oppression. So that’s the real message: social and environmental justice are two in one— they are not to be distinguished.”