Shame. One of the most wretched, and subsequently, most powerful emotions humans are capable of experiencing. As a result, the emotion can be utilized as a tool of control, and is consistently used as such, often in a manner that is easily overlooked.

People are constantly inundated with shame, whether it be about their bodies, identities or beliefs, and all too often, the driving force behind these negative feelings are large entities, such as religious groups, with a personal interest in manipulating the individual.

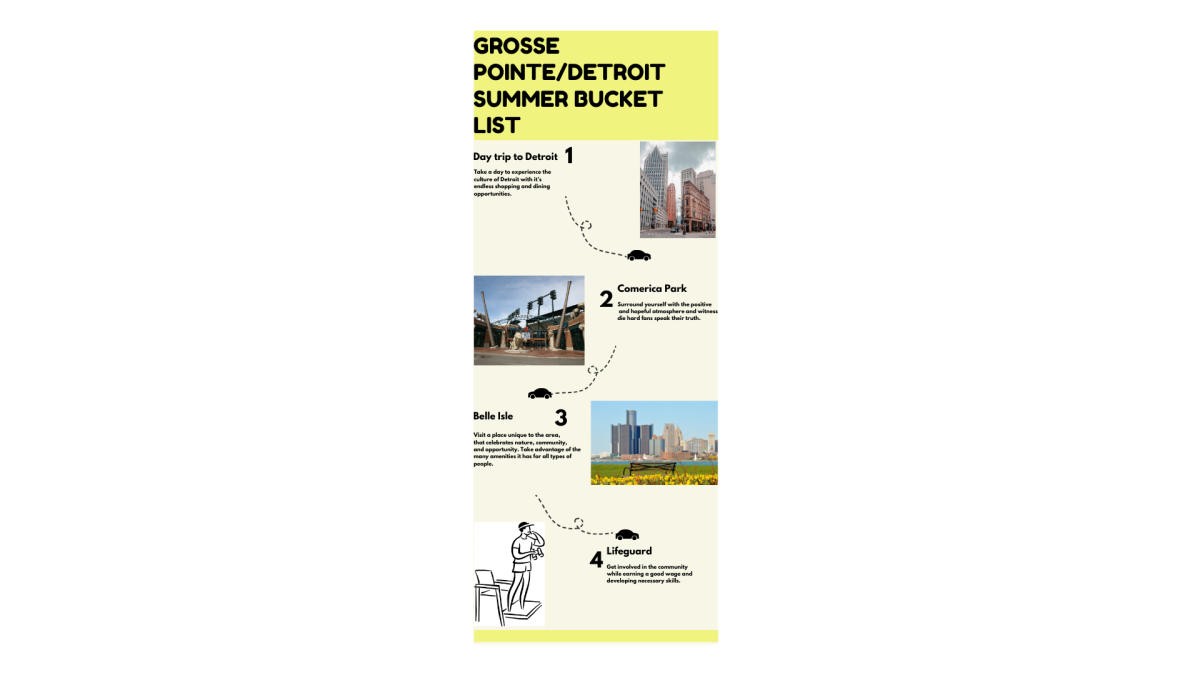

The history and culture of the United States is deeply rooted in religion, specifically Christianity and Catholicism. Grosse Pointe itself was established by French Catholics in the 18th century, and as a community, maintained its Catholic foundations throughout its further development. To this day, roughly 67 percent of the Detroit metro area identifies as Christian, with Catholics being the second highest denomination, accounting for about 24 percent of the entire group.

As a community with deep roots in Catholicism, it’s inevitable that shame, even if it is no longer consciously taught, has seeped into other institutions, surviving unnoticed, yet still with the same potential to do harm.

Erin Webber, a therapist with two degrees in psychology from the University of Michigan, has worked at her own private practice for 15 years. In that time, she has primarily worked with students in the area, many of whom have struggled with the effects of shame.

“Shame is one of the worst things we as human beings are capable of feeling,” Webber said. “ It truly is the master emotion, in that it’s the most uncomfortable thing to feel, and therefore we want to avoid it at all costs. So it can be a very powerful tool for parents or institutions, including religion, to use either intentionally or unintentionally to control or influence people.”

With such prolonged experience working with younger people in the area, Webber said she has come to gain an intimate understanding of the specific environments that perpetuate shame.

“Regardless of the religion being practiced in any given household, I believe there is a way to hold it sacred and still be open to other ways of life and different belief systems,” Webber said. “Shame has more room to grow in a home that has a very closed belief system. It creates a culture of only one right, which means a variety of wrongs. When someone lives under these conditions, it can cause fear of ‘being wrong’, as well as chronic internal and external pressure to be something that perhaps you are not. This creates what is called cognitive dissonance, or the ultimate internal battle.”

Webber said she has also developed a deeper understanding of the specific mindsets shame can foster, and the connections these mindsets often have to family and religion.

“I do often see in therapy, people coming in feeling immense guilt or shame for things like not being ‘good enough’, or a struggle with their sexual orientation, or their relationship to their own body,” Webber said. “Often, it can get traced back to the religion of their family of origins, including Catholicism.”

While Webber acknowledges the potential religion has to perpetuate shame, she also sees spirituality as a possible avenue for personal enrichment.

“I have studied many different religions, and have a sincere appreciation for them, and how they aim to connect people with love, hope and grace in various ways,” Webber said.

Christian Potts ’23 is a practicing Catholic at St. Paul Catholic Church who, similar to Webber, sees his faith as a source of love and understanding.

“Being a Catholic isn’t just about believing in God, it’s also about loving everybody for who they are and protecting the world that God gave to us,” Potts said. “It’s about doing the most that we can with the time that we have.”

Monsignor James Bilot, who works at St. Paul, said he feels the Church’s job as an institution is to help redeem those who feel shame, which he feels has become especially important in recent years considering the abuse that has come to light surrounding the Catholic church.

“What’s really important to know is that the reason Jesus instituted the church is because we needed somebody to redeem us, because of our shame, because of our sin, because of our brokenness,” Bilot said. “What we’ve learned from all this, is that if somebody has been in an abusive situation, (they) need to break the cycle.”

Although the church is not proud of the abuse that thrived within the culture of the religion, Bilot is adamant that confronting the uncomfortable truth is crucial in helping to end the cycle of abuse.

“If you’re abused, (you) usually tend to become the abuser,” Bilot said. “So what we’re doing with all this is trying to break that cycle.”

Coordinator of Evangelical Charity and Service, Tricia Kesteloot, who also works with St. Paul, said she feels that shame does not belong in the church, and that those who utilize it systematically do so against the will of God.

“No one has the right to shame or mistreat others in the Lord’s name. Period,” Kesteloot said. “Everyone should be treated with dignity and respect. I know that it wouldn’t surprise anyone if I said that people often take the church’s teachings and manipulate it to meet or conform to their own agenda.”

Kesteloot also feels that, even if not directly imposed by the church, shame in any form does not belong in Catholicism, and that it is the duty of the Church to help reverse the process of shame in our society

“Unfortunately, shame is an unfortunate part of our everyday culture,” Kesteloot said. “For many within the church, there is a sense of shame that stems from the wrongful actions of others. At St. Paul, I continue to appreciate that our pastors have not looked a blind eye to these conversations and have publically shared that in their homilies. Shame and abusive actions towards others are not a reflection of God’s love for us or the institution of the church. Living in shame is neither healthy nor part of God’s plan for anyone.”

While not actively religious himself, Logan Detweiler ’23 comes from an ardently religious extended family, and having lived in the Grosse Pointe for nearly his entire life, Detweiler said he has noticed the underlying culture of shame in the community.

“I think it’s deeply embedded into Grosse Pointe culture to shame others for doing things differently,” Detweiler said. “Maybe it’s not something that’s really contained to Grosse Pointe, but I see it here regardless.”

Detweiler feels that Grosse Pointe’s size greatly contributes to this aspect of its culture, as there is a general feeling that ‘everyone knows everyone’.

“Grosse Pointe is a very insular community, so I think it amplifies the shame you feel,” Detweiler said.

While shame still persists in Catholicism, and has, more notably, rooted itself in our culture, psychologist Erin Webber said she feels that the emotion is not inevitable, and is in fact able to be countered with self-acceptance.

“Be gentle with yourself,” Webber said. “The thing I believe Catholisim struggles with most is teaching self-compassion and acceptance. The irony here is that, the more we are able to love, accept and have compassion for ourselves, the more we are able to have these things for others. We cannot give anything to others that we cannot first give to ourselves. It’s alright to want to be better in some way, as long as it’s rooted in compassion for yourself and you give yourself some grace and time to make changes.”