Definition of school differs across districts

April 21, 2020

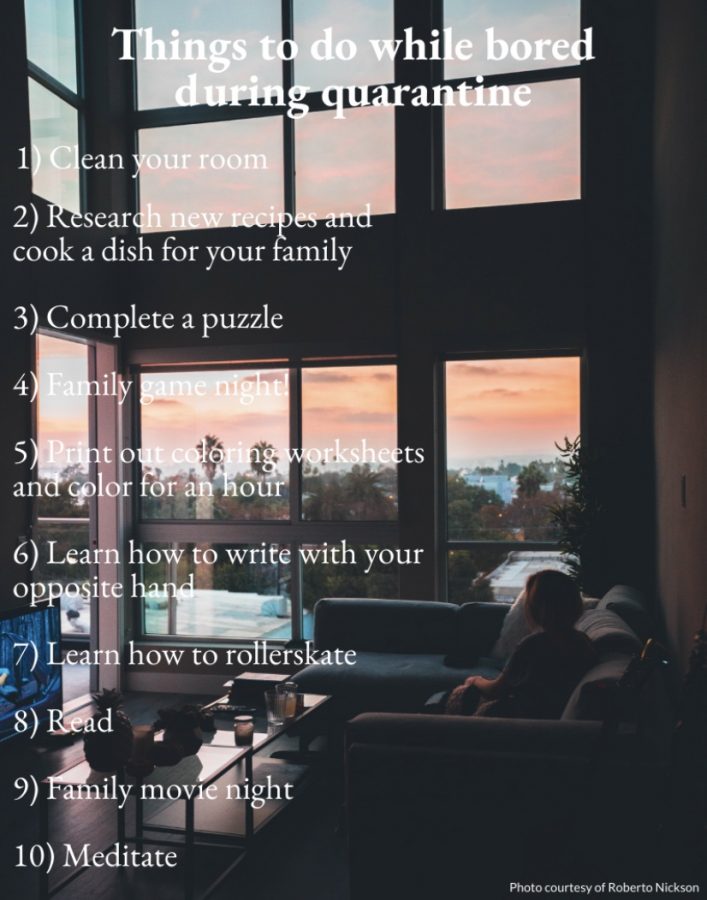

Synchronous block schedules. Enrichment learning. Minimal communication. Across the state, school districts are handling closures in many different ways.

Before Thursday, March 12, when Governor Gretchen Whitmer announced the closure of all K-12 school buildings, the impact of the coronavirus felt more abstract, according to South physics teacher Todd Hecker. He said everyone thought it was similar to the flu and not dangerous to the general population.

“I think earlier that week many people, myself included, thought people were overreacting to the virus,” Hecker said. “As more and more colleges began closing, I think people figured it was only a matter of time before the schools closed.”

This was a common sentiment across Metro Detroit, according to Helen Devine ’20, a senior at Wylie E. Groves high school in the Birmingham Public School District. According to Devine, there wasn’t much talk of the virus at school until that Thursday.

“Suddenly, in every class teachers were mentioning the virus because they had planned to close school the following Monday to regroup as a staff,” Devine said. “Before then, no one had talked about it at all. It was more of a sense of optimism over planning ahead.”

Anna Gill ’21 attends Canton High School, and she said initially there was not any communication from the district after Whitmer’s announcement to explain what would happen next.

“After the announcement, we had an email that was very just general what COVID-19 is and how to prevent it but nothing about school closures,” Gill said. “It was not until Friday when we found out we would have no school. The teachers were not not to assign anything, so we just had the first week off.”

Teachers at South spent Friday, March 13, meeting and coming up with a plan for remote learning, from online assessments to video conferences, according to Hecker. He said this allowed a smoother roll out for online curriculum.

“I’ve been blown away by how well it’s been handled,” Hecker said. “Everything I’m hearing is that teachers are continuing to teach, with reduced expectations and increased compassion.”

According to chemistry teacher at Lakeview High School, Laura Hull, their district did not have much time to prepare for the transition to online classes. As a district, they made the decision to only provide optional assignments.

“We didn’t make any assignments required. There were no deadlines, so they were just interesting resources as supplementary material,” Hull said. “There was no new material. It was just a review and allowed students to dig deeper.”

At University High School Academy, a part of Southfield Public Schools, Donovan Roger ’20 said the school has begun to shift to a block schedule for remote learning. Students attend two to three classes through conference calls each day.

“(The block schedule) gives students a lot more time to settle in to this new period of opportunity, and it brings us a lot of restoration and relaxation and having classes starting at 11 a.m. and only three hours a day– opposed to a class starting at 7 a.m. with eight hours a day,” Rogers said. “Our district had already issued Chromebooks and other resources out to students.”

Equity has been a big component in planning for remote learning across the area. It is not fair to require students to complete work online when they might not have the resources to complete it, according to Devine.

“In my school district’s first response, they said they were working on a program to allow students to pick up laptops if necessary, but this never happened,” Devine said. “The district just made a statement saying none of the work is required, so it is okay if you have extenuating circumstances and need to reach out to the principal.”

Gill said her school had an initiative to distribute Chromebooks, but it was not well publicized. She expressed concern in the discrepancies of online learning on the basis of resources.

“We have students that might not have internet access or computers, so if they missed the one announcement to apply for a Chromebook, they won’t complete anything,” Gill said. “They have nothing. The students signed up for AP exams have no communication with their teachers, and they might not know testing is online.”

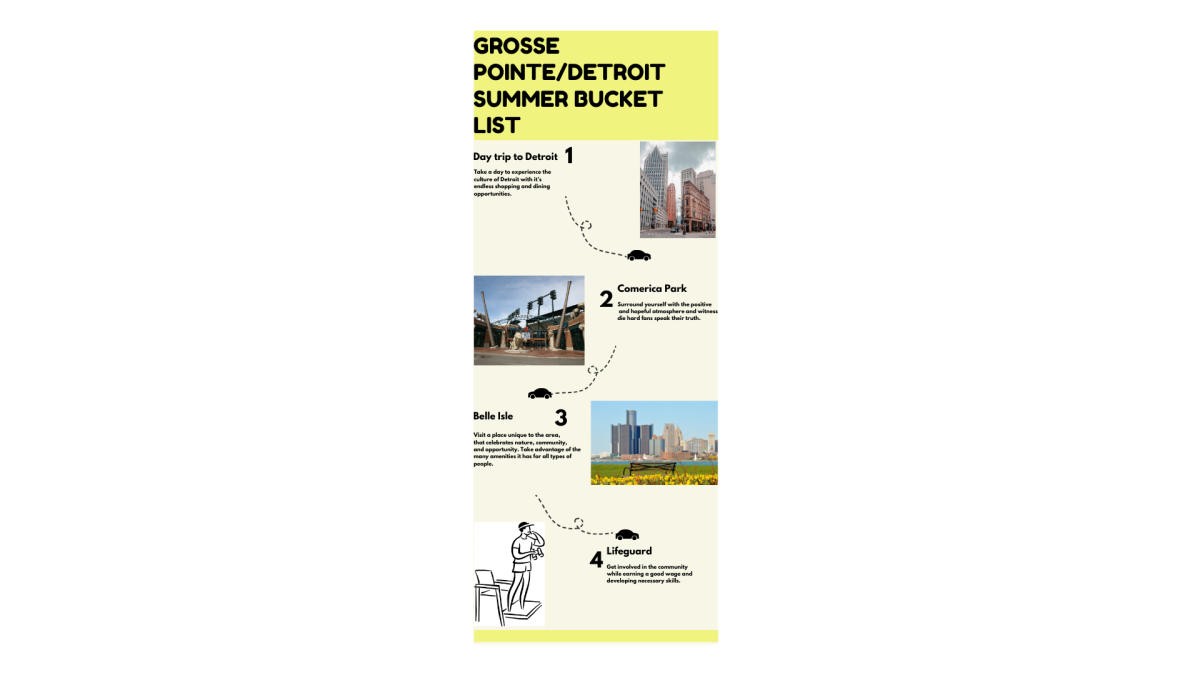

According to a tweet by the Grosse Pointe Public School System, at least 750 Chromebooks have been checked out by students during this time.

Other districts across Metro Detroit, however, may have other factors limiting the amount of required work at the moment, according to Hull.

“Some of our students are at a different socioeconomic level than in Grosse Pointe,” Hull said. “I know a lot of my students have had to get jobs. They are working at grocery stores or taking care of their brothers or sisters.”

Both Hecker and Hull agreed that there are some inherent disadvantages of remote learning. There is no easy substitute for the face-to-face connection between students and their teachers.

“You lose the in-person engagement, things like reaching over and giving a high five or a smile,” Hull said. “These connections can motivate students especially because we don’t know what their situations are or what their daily-life looks like. I don’t have a way to check in on their emotional wellbeing.”

At the moment, education is understandably taking a backseat as families focus more on keeping their community healthy, according to Hull. She stressed that students should know that their teachers are understanding and simply want them to stay curious and engaged for the time being.

“This is new to all of us; there is no guidebook,” Hull said. “I hope my students are taking a step back and assessing what is important to them. I think we’re able to appreciate school a little more now.”