The gentrification issue in Detroit

The city of Detroit, for many who have grown up in the bubble that is Grosse Pointe, used to be much like the distant relatives people visit once or twice every year, if that. Aging, worn around the edges, long past its heyday. A place loved for its traditions, for what it used to be, instead of a place to walk or bike through with friends.

For many who grew up in Grosse Pointe, Detroit was a place where rites of passage took place, nothing more. Our first volunteer work. Our first Tigers, Lions or Red Wings game. Our first trip to Belle Isle, or Pewabic Pottery, or the DIA.

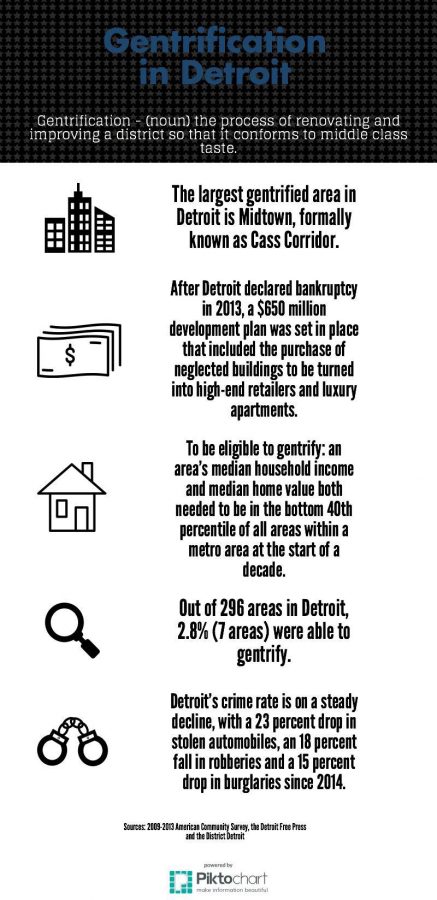

At its bottom, the city of Detroit had one of the highest rates of unemployment in the country, rising to almost 50 percent in 2010 according to the Detroit News. In 2013, Detroit became the largest U.S. city in the country’s history to file for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, according to USA Today. According to FBI crime statistics reported by the Detroit Free Press, the city had the highest 2013 homicide rate in the nation, and Detroit received the number-one spot on Forbes’ Most Dangerous Cities ranking several years in a row. For some in Grosse Pointe, the city of Detroit inspired fear. It was a place to be avoided at all costs, rather than to be explored or celebrated in any way.

Those dark days seem to be coming to a close, and now Detroit is less like a distant relative and more like a close friend.

Yet with this improvement comes concern from some citizens that Detroit is undergoing gentrification– a sometimes harmful process that involves urban areas being developed by young business owners without concern for the low-income individuals and families who lived there originally.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of employed Detroit citizens has increased by 15,000 since 2014. For every month in 2016, Detroit’s employment growth was greater than the state and national averages. Overall, the rate of unemployment for the city has been reduced by half.

Dave Mammel, General Manager of Jolly Pumpkin Pizzeria and Brewery, said the restaurant employs 55 people, many of whom are Detroit residents who might have had trouble finding employment due to the state the city was in a few years ago.

Jolly Pumpkin, which opened back in 2015, is one of many restaurants and shops that has opened in the Midtown area in the past few years. Mammel said because Jolly Pumpkin is known for their beer, the goal was to price their items reasonably– the restaurant is at a mid-range for pricing because of their locally sourced ingredients and items prepared in the restaurant daily.

“We weren’t really looking for the high-end pricing, but we have the ability to charge a pretty good price that caters to a lot of people,” Mammel said.

Mammel said the rush of new activity in Midtown is a great thing. Not only because of new business openings, but things like Eastern Market appearances are attracting attention and curiosity toward the city.

“I’m seeing a lot of people that wouldn’t necessarily come to Detroit and check out the new restaurants and shops, and the price of housing and rent increasing a little bit here and there, people moving closer to Midtown and into the neighborhoods surrounding it, and you see it (the city) coming around, it’s a great thing,” Mammel said.

Mammel said the mixture of high and low-end stores and restaurants in the downtown area is a largely good thing. He said it attracts different types of people who can enjoy themselves at different price ranges.

“People are seeing the growth in Detroit and people are wanting to open businesses,” Mammel said. “There’s a lot of local things that people are seeing and wanting to come down to the area to check everything out.”

Mac Farr, the Executive Director of the Villages Community Development Corporation, said higher prices don’t necessarily equate to gentrification.

“If you’re having these stores that are popping up, to me that’s an indication that they’re actually matched to the underlying economic demand of people that are moving into Detroit, so that’s a good thing,” Farr said.

Farr said, especially of the shops opening in Cass Corridor, that previously the buildings were grossly underutilized, if anything existed there at all. That, according to Farr, isn’t necessarily gentrification, but rather badly needed economic development. The activity in the building, the fact that money is spent, jobs are created with the opening of a business and the fact that the city is now getting income tax from that business are all positive things, he said.

More than gentrification, the issue in Detroit is displacement, Farr said. He said both in a commercial and residential context, when stores and apartment buildings open that are substantially pricier than those that came before them, it presents a number of issues.

According to Farr, 1214 Griswold St. used to be subsidized senior housing, and was recently turned into luxury apartment buildings. These apartments now cost three or four times what the last group of tenants were paying. Farr said this is a prime example of displacement that is fueled by gentrification, and that while Detroit is not yet at the point where there is large-scale displacement, the city will reach that point.

“I’m very hesitant to cast anything as either good or bad; the city needs a lot of development in order to pay for the city services that our most vulnerable Detroiters rely upon,” Farr said. “Ambulances don’t pay for themselves. Police protection doesn’t pay for itself. The Fire Department doesn’t pay for itself. Those come from income taxes and property taxes. And in order to have a fully functional city government that protects the weakest amongst us, we need to welcome that kind of investment and development that can actually pay for it.”

However, looked at from the perspective of Detroit residents who have lived in the city for decades, the changes taking place in the city can be shockingly detrimental.

Anzen Melanie Davenport from the Still Point Zen Buddhist Temple said they tried to find a second location to expand the services the temple offers, but they had to abandon the idea because real estate prices have soared in the past few years. As long as the buyer was motivated to renovate the house, there were homes available for $20,000 to $30,000, she said. Now, that’s out of the price range for many.

According to gentrification data from governing.com, the median home cost in the city has undergone a 126 percent increase in the past 17 years.

“Older people who are not able to go out and get really high-paying jobs, they’re going to suffer the most here, because things are changing very fast and there’s no consideration for where they’re supposed to live, especially since older people are kind of the keepers of the history around here,” Davenport said.

Additionally, the changes the city is undergoing have created racial tensions, according to Davenport. The rapidity of the growth, Davenport said, has prompted resentment among African-Americans who have been here for decades, investing what little money they had into their businesses, toward white middle-class people who bought large amounts of property without consideration for the people who were there beforehand.

“I can see that animosity, sort of tension brewing,” Davenport said. “I also see a lot of white middle and upper-class people who have never been to Detroit, or never have lived in Detroit, never really socialized with anybody in Detroit, kind of experiencing their own little cultural shock, where they kind of don’t understand the culture that was here, they don’t associate with black people in any meaningful or long-term way, so they kind of don’t know how to approach things.”

In addition to the tensions caused by these developments, Davenport said there are a lot of new stores that have opened whose prices are a bit too high for the city. While it’s good to have stores that get a lot of foot traffic, because the stores are very high-priced and small, there are not too many jobs they could be providing, she said.

“So it’s good in that people come through to visit from other places, they have a nice little enclave to visit, but I don’t think places like that can generate a whole lot of economic growth because they’re not able to hire people in the neighborhoods, and then conversely, if you give people jobs around the neighborhoods, they’re able to buy more,” Davenport said.

However, Davenport said she has seen the neighborhood surrounding the temple change overall for the better since they opened in 2003.

“The houses that are there, townhouses, those weren’t there. That was a vacant lot,” Davenport said. “A lot of the houses on the streets when we came here were not in very good condition, if people were living in them, or nobody was living in them and they were in pretty poor condition.”

According to John Roach, the Media Relations Director for the Detroit Mayor’s Office, the city has done a lot of work to revitalize dilapidated homes around the city. This work benefits a lot of long-time residents of the city who are struggling.

“We’ve taken down nearly 11,000 blighted homes and neighborhoods across the city. Another 3,000 homes that were vacant and are being renovated and reoccupied in neighborhoods across the city,” Roach said. “As a result, property values in these neighborhoods have increased significantly.”

According to the Detroit News, a development team was chosen on April 5 to redo 115 vacant homes over the course of two years. The plan is estimated to cost $4 million, and it will also create a two-acre park and landscape 192 unused lots on the city’s northwest side, in the Fitzgerald neighborhood. The area will become the Ella Fitzgerald city park, and a quarter-mile greenway path will be added to connect it to Marygrove College.

“As simple as it (the development plan) appears, I think it’s revolutionary in Detroit,” Maurice Cox, head of the city’s Planning and Development Department, said during a news conference on Wednesday, April 5.

Roach said the Motor City March is also benefitting Detroit businesses. The mayor introduced the program to encourage entrepreneurs in the city, and two-thirds of the businesses that have benefitted are owned by African-American Detroit citizens, many of which are opening in neighborhoods surrounding Midtown and hiring other Detroit residents to fill the jobs.

“You could make the argument that as Detroit becomes more expensive, that’s a recognition of the fact that things are getting better here,” Farr said. “So just because things are getting more expensive, it’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s almost like Detroit is catching up.”