As with every beginning to the school year, students fall into their routine of walking from class to class and jumping right into assignments and tests. However, this year there is a new step in the daily routine, a new procedure to help enforce the district wide Off-And-Out-Of-Sight policy: the phone caddy. Upon entering each class, students are asked to drop their phone into either a box or pouch before they sit down to learn.

Assistant Principal Cynthia Parravano acknowledges that the new policy may be controversial, but she hopes students can understand the need for change and the reasons behind it.

“We want [students] to benefit from the education that they’re getting at Grosse Pointe South,” Parravano said. “Every time that phone goes off and you’re distracted by it, you’re losing what is happening in the room and everybody says, ‘Well, I can multitask, right?’ But you can’t.”

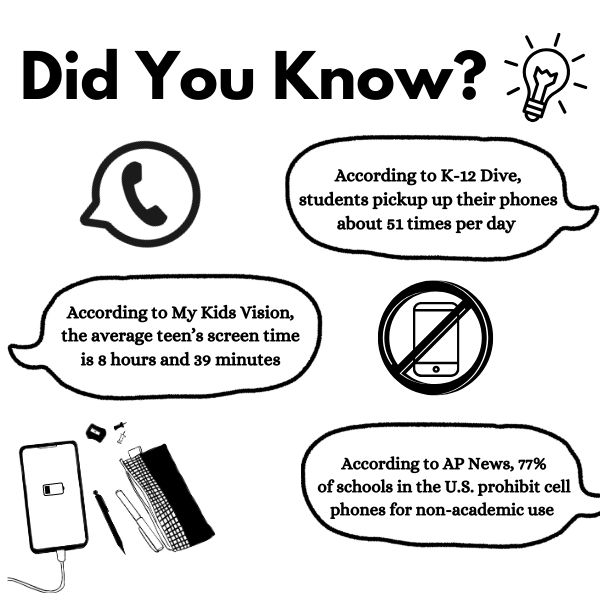

Technology, and phones specifically, have become embedded in everybody’s daily life, even as tools for school purposes, but Parravano believes this is indicative of a larger problem.

“We’ve got a phone epidemic and everybody is addicted to their phone,” Parravano said. “I think we need to encourage students to put their phones away and engage with people again, engage with your teacher, engage with the class. Learn as much as you can. Use your phone as a tool and don’t utilize it as a lifeline.”

Perhaps one of the most popular places to sneak a phone is the library. During tutorials or virtual classes, it’s easy to check a text in the larger environment. Courtney Johnson, the school librarian, has implemented the new procedure and has been surprised by the reaction she has received.

“I thought for sure I would get some pushback or stink eye or protest, and they have been very compliant,” Johnson said. “I think it’s helpful because I truly think students are addicted to their phones.”

However, Naya Azoury ’25 has a different perspective and believes that teachers taking phones at the beginning of class won’t solve anything, but punishes students who are already being attentive in class.

“If [students] were on their phones, it was for a minute, nobody’s on their phone the entire hour, and if they are, that’s their loss,” Azoury said. “Also, I think that we should be able to have our phones and learn self control, because if we’re not learning it now, when we go to college, what do you think’s gonna happen? Because they don’t care there.”

But to the administration, it doesn’t matter how many kids are on or off their phones as the consensus is the same: students had their chance to be responsible and weren’t.

“Teachers were saying they needed some additional ways to be able to help institute the policy because what they’re doing is not working, and we keep telling kids: ‘put your phones away, put your phones away, put your phones away’,” Parravano said. “And so, how many times does that interrupt the teachers (that are)teaching or helping other people?”

Azoury still believes there shouldn’t be a blanket treatment for all students, and that teachers should’ve just enforced Off-And-Out-Of-Sight more diligently .

“I don’t think that people who do pay attention in class and are good students should get their phone taken away,” Azoury said. “It’s a punishment, like they’re my parents. If a teacher sees you on the phone, they give you a warning. If they do it again, then they’d say ‘Give me your phone for the rest of class’ and that’s what I think it should be. That also teaches discipline and self control, not just taking them away.”

Parravano anticipated students’ unhappiness towards the new procedure, but argues that the caddy system isn’t even that harsh compared to other schools in the state.

“I think Northville just said phones can’t be in the school period and we see what other schools are doing and think we’ve got to come up with something that is balanced,” Parravano said. “Something that gets them out of their hands, because we want you focused on learning, but so they’re still available to you. You want to call your parents, you want to text somebody during lunch period, fine. So we needed to do something that was kind of like a medium.”

However this accessibility has been questioned not just by kids, but by parents as well. Renee Jakubowski, a mother of two South alumni and a current sophomore, says kids will find ways around the ruling anyways, which is why students should be able to keep their phones for communication purposes.

“My child has shown she is capable of focusing on school even when her phone is with her so she should not be stressed wondering if I’m going to be there with her gear or permission slip because she couldn’t tell me,” Jakubowski said. “If some kid is playing on their phone or using social media they can do that on their laptop anyway. Not having their phone isn’t going to stop them.”

Parent and child communication is very important during the school day and unfortunately that communication has only become more important in a time where school shootings are a common occurrence. On September 4th, Apalachee High School was the newest mass shooting site and during it, kids texted their parents very emotional messages. These messages are why Jakubowski heavily disapproves of this new procedure.

“As shown in the latest school shooting, kids were sending texts to parents and they could at least begin to be nearby if needed and provide comfort,” Jakubowski said. “As we have seen after the Michigan State shooting, technology is being used to communicate better to prevent needless loss of life. Scrambling to the caddy to find your phone when you should be either taking cover or making an escape is antiquated and dangerous.”

It’s unfortunate that these are concerns that students and parents need to have in the first place and Parravano acknowledges their validity, but she also reiterates that the phones are still accessible to students.

“There are some schools that are making you lock it up and you’ve got this pouch, you’ve got your phone, but unless you go to the pouch with a magnet, you can’t open it up. Our teachers are not saying ‘Don’t ever touch it’,” Parravano said. “If there’s an emergency, I would expect you to get your phone right. But during class time, when you’re in a room that is secured, I want them away from you so that you’re focused on learning. If there’s something that happens, they’re right there.”

Despite these comments, both upper and underclassmen have issues with the policy. Zion Jones ’28 plainly says that he thinks it’s stupid.

“What if my Mom is trying to reach out to me and tell me something?” Jones said. “It’s keeping me off the wire.”

The hope is that both students, parents and administrators will be able to move forward into the school year as a cohesive group when it comes to enforcing the phone policy. Parravano concludes by saying it’s not even about the phone, but about students as individuals .

“The phone is not an evil thing, it’s the way we’re using it, and the way we’re occupying our time,” Parravano said. “We’re distracting ourselves from things that really matter with social media stuff and it needs to change.”