Navigating the discourse on race within the classroom is a complex and often challenging endeavor. As educational environments strive for inclusivity and diversity, the difficulties of engaging in meaningful conversations about race become apparent. Tackling this sensitive topic requires educators to confront deep-seated societal issues, grapple with uncomfortable truths and address students’ unique perspectives. Striking a balance between fostering open dialogue and maintaining a safe learning space is a delicate dance, with potential pitfalls of misunderstanding, discomfort and resistance.

Retired teacher Jay Marks said that curriculums are often eurocentric—conveying the point of view of the often-European victors in history—rather than giving representation to minorities. During his first job at a majority African-American school, Marks said he integrated opportunities to give voice to non-European sources to better engage students with history.

“I refused to teach my students a curriculum that did not honor, celebrate, affirm and validate their identities,” Marks said. “If the textbooks had any pictures of people like them, they were typically at the margins, not highlighted.”

According to Marks, a narrowly-focused curriculum harms the education of students of all students, no matter their race and its effects could have a long-lasting detrimental influence on people’s biases and opinions.

“White children, unfortunately, are getting the same education as our students of color,” Marks said. “They have things that they want to say, they should have a voice, they should have an opportunity to speak and learn more about race or racism and the experience of different groups of people. Having these conversations aren’t just for our students, staff or families of color, but all of us because we share humanity.”

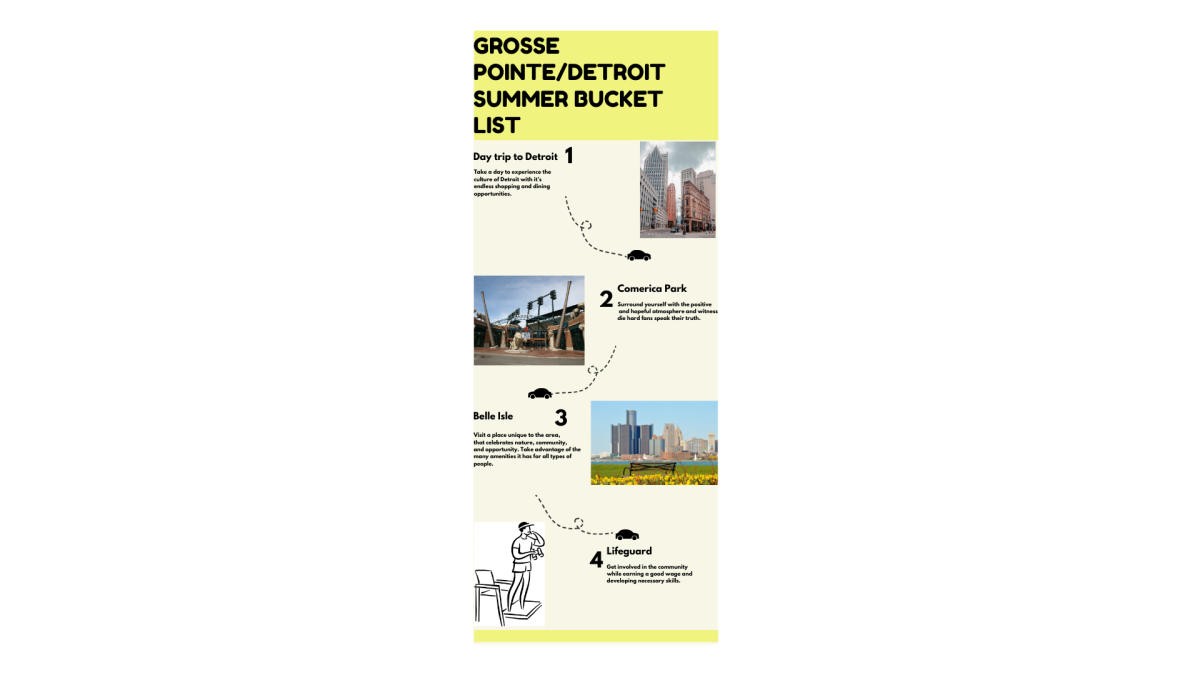

Students Empowering Education for a Diverse Society (SEEDS) President Mia Fakih ’25 said she agrees that a lot of the teachings found in schools—including some in Grosse Pointe schools—can be harmful to students.

“A lot of times, there are misconceptions of people from different races resulting in stereotypes that a lot of people in South carry with them,” Fakih said. “It’s important that we teach them that these misconceptions aren’t true.”

Though Fakih said she thinks that there is an importance to teaching these things, she said she believes that students can not learn if they refuse to be receptive to alternative perspectives on the issue.

“It’s not (students) jobs to teach themselves about (race and stereotypes),” Fakih said. “It’s their job to be open minded and be willing to learn.”

Naya Azoury ’25 said that it’s not always obvious when a topic is going to be uncomfortable and that the situation is inevitable.

“It’s difficult when we talk about slavery, but it’s also difficult when we talk about 9/11 or colonialism in America,” Azoury said. “You never know when a student is going to be affected by a topic, because they’re not always going to be open about it. It’s almost like someone is always going to feel uncomfortable when these topics come up.”

Because Grosse Pointe tends to lack the diversity that many other communities have, Azoury also believes that there is a large amount of pressure applied to students of specific ethnicities to represent their group within conversations on race.

“If you’re ethnic, it’s like you are expected to speak on behalf of everyone of your ethnicity,” Azoury said. “People have different opinions. Your beliefs aren’t attached only to your race, they’re attached to your environment and your experiences.”

After years of teaching, English teacher Erika Henk has learned how to appropriately discuss race and slavery in her classroom. As a teacher of Honors American Literature, slavery and the topic of race often comes up in the curriculum, which puts Henk in a position that requires much delicacy.

“I definitely wish that I would have been guided a bit in that area,” Henk said. “It is difficult no matter who you are, but as policies have been put into place, my confidence has grown.”

Similarly to Henk, Booth said he noted how his college education lacked information surrounding race in the classroom. In order to account for this, Booth has attended workshops and guest speaker presentations during his high school teaching career.

“Even as a U.S. history teacher, race was only a part of the class term, but they never taught us strategies on how to teach future kids,” Booth said. “Guest speakers) have talked on bias, understanding, and overall strategies in the classroom, so (teachers) have had some diversity, equity and inclusion training.”

Regardless, many teachers don’t have the tools to most productively forward the conversation. . While acknowledging the difficulties this presents, Henk said she still recognizes the importance and value of discussing race in the classroom.

“It’s a volatile topic in our world,” Henk said. “This stuff, even though it’s history, is still important to discuss because it’s still happening today and will happen in the future.”

Azoury said she believes although the conversation surrounding race is imperative, she believes the world must power through unavoidable obstacles in order to truly make progress. . She believes if people aren’t versed in the subject, they are more likely to be susceptible to misinformation and inaccuracies about communities they aren’t a part of.

“If we don’t talk about (racist incidents), there’s a chance of them happening again,” said Azoury. “We see that with so many different pieces of our world right now. History is repeating itself right in this moment and it’s sending us in the wrong direction.”

Fakih also recognizes how difficult it is to be teaching material that has to do with race, and said it’s not purely their responsibility to inform students on complicated matters. Students too must take charge outside of the classroom in order to progress society to a more understanding place.

“Teachers already have to tiptoe around everything they do,” said Fakih. “They have to be careful of what they say and teach in fear of backlash from the board—I’ve seen that happen. With that in mind, the students also need to take some initiative and try to educate themselves as well.”

Marks believes that students should be the decision makers in educational spaces. He said students should have a say in what they are learning considering they are the recipients of the instruction.

“There could be barriers for (minority) students making it more difficult for them to learn in certain spaces,” Marks said. “They shouldn’t be spoken for. Those who are in the conversation should notice that there are people missing and speak up about it.”

He also said that another contributing factor for the difficulty in conversing about racial subjects in the classroom is due to people fearing offending others.

“People fear that they’re gonna say something offensive or they think that they’re going to hurt someone or themselves,” Marks said. “They’re afraid that they’re going to be misunderstood or their beliefs are going to label them as racist, even if they only said it out of a lack of information or ignorance.”

Booth said teachers and students must confront any difficulties because this conversation is the backbone of the American melting pot. According to Booth, every unique identity combines to create a better nation for everyone, and avoiding the subject will only limit each person’s understanding of their fellow Americans.

“That’s what makes this country great; we’re not all the same,” Booth said. “We don’t have the same backgrounds. Every kid or every person in this country has a different background and has a different story, so we all feel differently about different aspects about race in America. That makes it very important to discuss.”