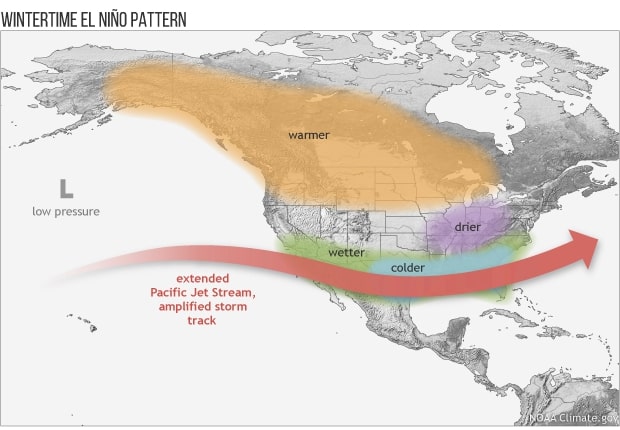

It’s an “El Niño” year – temperatures are really high and there will be very little snow; what does this show in terms of the progression of climate change, and how does this differ from normal Michigan winters?

El Niño is the common name to describe when the water at the equatorial Pacific becomes warmer than average and the east wind blows weaker than usual. The opposite of this effect is called “La Niña” which brings colder than average temperatures.

Climate change is the agreed upon cause for these irregularities, with some dispute in the scientific community. El Niño and La Niña vary in impact every cycle, transitioning every 2-7 years.

El Niño has been plaguing Michigan for thousands of years, bringing a slight increase of hotter weather during the winter season. It provides a drier season with slightly warmer temperatures and less precipitation. The chance of wildfires and droughts around Michigan are increased. While the common midwesternor won’t notice the slight changes, these waves of hot air have been slowly increasing in strength, raising concerns for experts.

The warmer weather decreases ice coverage on the Great Lakes, now hitting a record low. Only seven percent of water is covered by ice, compared to the usual 30-40 percent of coverage, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. The main factor is the air temperature, which has been getting hotter and hotter. In the 44 years between 1973 and 2017, the Great Lakes ice coverage has decreased 70 percent. This staggering decrease caused by global warming is amplified by the El Niño phenomenon.

El Niño also brings faster and stronger ocean currents which can disrupt local ecosystems. Michigan’s Great Lakes ecosystem and fish life are greatly affected by El Niño. Warmer weather creates a disruption in the food chain. The cold water fish in the lakes, such as Whitefish and Trout, are forced to compete for the same food sources as warm water fish. These warm water fish have migrated north to warmer water caused by El Niño. This shift in location and ecosystems puts pressure on both groups of fish, especially the cold water fish. Mammals are feeling the heat too, for example, the increase of migration north for moose. With the warmer, shorter winters, moose are becoming more susceptible to brain worms and ticks, according to the National Park Service.

This change in weather is becoming more drastic, warming the planet more every El Niño season. Research done by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that El Niño’s extreme effects have intensified by ten percent from pre-1960s statistics. Ten percent doesn’t sound like a lot, but the same experiments done with advanced computer simulations suggest that a snowball effect could occur, doubling the frequency of extreme weather events in the next century. The long cyclical nature of El Niño and La Niña makes tracking the effect of climate change on them difficult. However, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts more extreme El Niño and La Niña effects in the future.