Affirmative action is, without a doubt, a highly debated and polarizing issue and has been for a while now, and as a result, the Supreme Court has been forced to intervene. More recently, the Court has banned race consideration when used as a point accumulation mechanism in college admissions.

AP US Government and Politics teacher Andrew Taylor discusses affirmative action each year as part of his curriculum and has his students evaluate college applications through the lens of an admissions officer. Of course, this year’s lesson may look a bit different.

“Can you consider someone’s race and the fact that they have overcome challenges that might be related to that? Absolutely,” Taylor said. ”But you shouldn’t just stop and say this is what we were looking for to meet a certain number of students from this group.”

Taylor’s claim explains how two wrongs don’t make a right, and selecting applicants primarily based on race not only creates hostility between groups of people, But it is also an inherently unconstitutional and discriminatory practice.

While numbers and GPAs are a reliable way to measure a student’s work ethic, counselor Jennifer Vick believes that there are other fundamental factors that should be considered. Students who lack in certain academic areas, for example, are often taught practical skills at a young age, such as hands-on experience in the workplace, that students who weren’t exposed to much outside of the classroom lack and that are valuable to both a college campus and a diverse international job market.

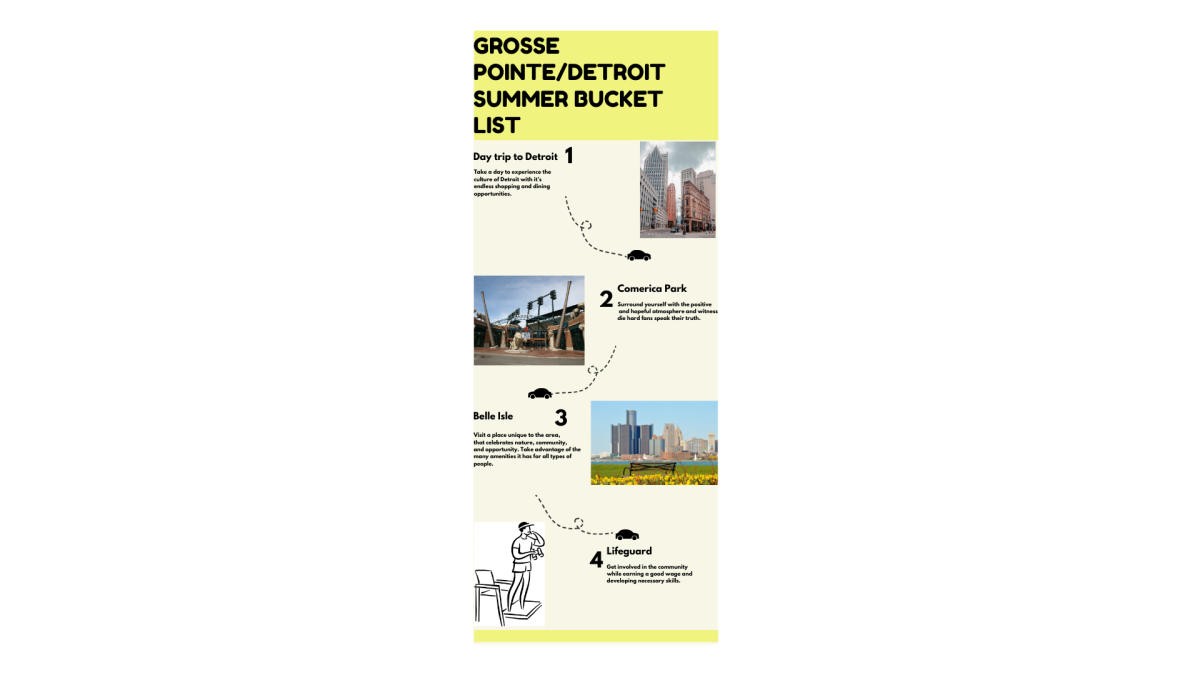

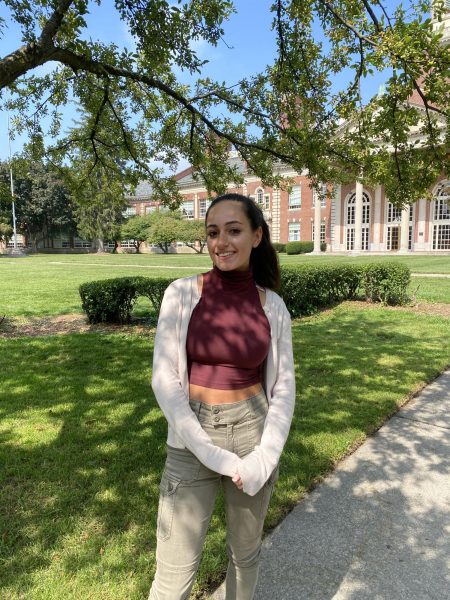

“Grosse Pointe South has a strong academic reputation that colleges know about,” Vick said. “And there are communities around us that don’t have the same resources, and as a result, should that impact students moving forward at the collegiate level?”When looking at a student holistically, U of M admissions officer Ava Butzu said that while race isn’t an automatic way to gain acceptance into a college, racial prejudice can and often does limit a student’s possibilities.

“Even a student who may be economically in a good place with a two-parent stable family may still face the issue of being prejudiced based on skin color,” Butzu said.

Butzu says that the struggles people encounter are worth considering when trying to grasp an accurate representation of who they are and that unfortunately sometimes race plays a huge factor in that.

Butzu also claims that having a high SAT score and GPA, while impressive, do not distinguish you in a way that demonstrates your abilities and unique qualities entirely.

“In the same way that if you applied to U of M and were academically qualified and you played the harp and we need a harpist, you’re really interesting now,” Butzu said.

Uncontrollable factors shouldn’t be considered in the college admissions process, according to Isaiah Thomason-Redus ’25 who hopes to study the french horn in college.

“You can choose to work harder or choose to really focus on something, but you can’t choose your race,” Thomason-Redus said. “That’s not something you have control of.”

More than race, Thomason-Redus said he believes the context of a student’s education should be much more considered in the college admissions process.

“Oftentimes, just as a result of where they live, people don’t have access to the same education or access to certain things that other people might have,” Thomason-Redus said. “In that case, you can provide them with what everyone else has, but you shouldn’t grade them by that.”

Because of the difference in resources for students between different districts, colleges will often recalculate each applicant’s GPA considering the difficulty of their classes and what school they attended.

“An A at South for a lot of colleges is worth more than an A at other schools,” Thomason-Redus said. “I don’t know yet how I feel about that, but the fact is that it does mean more if you get better grades here than other schools.”

A better way of determining who a student is would be looking at their education context rather than their race, according to Thomason-Redus.

“Colleges should consider how (students’) education was given to them, regardless of race, and their grades and how much effort they put in,” Thomason-Redus said. “Race shouldn’t be a big part of (admission).”

The many cases of practically perfect students being denied on the basis of their race made Liam Raether ’24 concerned as an Asian American. He said it comes down to numbers; there are simply too many Asians.

“I remember reading last year about this one Asian kid who got almost a perfect score on the SAT, wonderful grades; a perfect student who got denied from a multitude of schools purely in the case of Affirmative Action,” Raether said. “They just didn’t have enough space for another Asian.”

While some Asian students want to find more community at college, that can be a major disadvantage in the application process. If a school has a high Asian population, Raether said he would try to avoid applying there because he would be more likely to get denied.

“(One student) wrote a story about how she wanted to go to a college with many Asians where she could learn more about her Asian identity because she grew up in the Midwest,” Raether said. “She was trying to find a group of people she could identify with more and was denied from her simply because she was Asian.”

According to Raether, colleges have a high number of Asian students because of cultural expectations ingrained into the Asian community.

“I find Asian families tend to emphasize the need for college more and express the idea that college is what will make you more successful,” Raether said.

After the Supreme Court ruled Affirmative Action unconstitutional, Raether said he let out a sigh of relief. He said that he no longer has to base his applications based on the racial makeup of a school—something he had to consider before the decision.

“I had to look at how many Asians there were—and oftentimes it was a pretty big chunk—and often it discouraged me from applying to certain colleges,” Raether said. “I was worried that they wouldn’t take me because simply they didn’t have enough space for another Asian.”

Initially in favor, Liam Raether ’24 said his views on Affirmative Action have changed from a noble ideal to a system of contradictions.

“I’m not saying we should not have any protections against racism and prejudice in the application process,” Raether said. “I’m saying (that) while the goal of Affirmative Action was indeed noble, the practical application of Affirmative Action ended up hurting minorities instead of helping them.”

Historically, the Asian-American community has seen much discrimination in the US, from internment camps to exclusion acts. One of the biggest challenges Asians faced was Affirmative Action until its overruling, according to Raether.

“What was meant to help those who were disenfranchised in American history was actively hurting (Asians) as they were trying to be successful,” Raether said. “I felt that was inherently wrong with (Affirmative Action).”