Toxic positivity: How optimism can hurt, not help

January 21, 2021

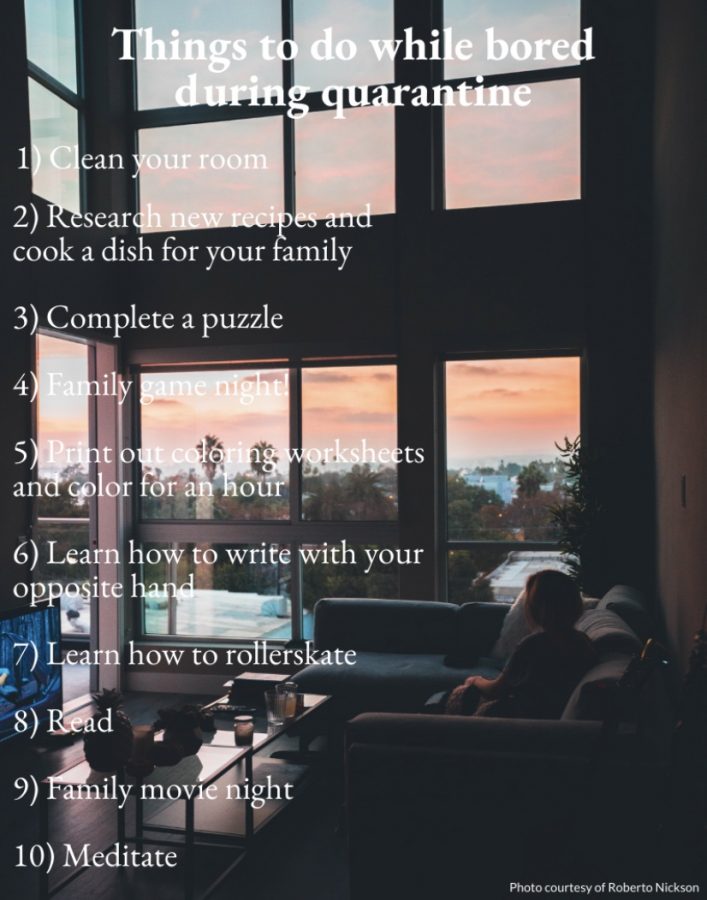

As the COVID-19 pandemic endlessly drags on, there has been a steady incline in mental health concerns according to South’s School Psychologist Lisa Khoury. As a result, more students now than ever before are reaching out for help.

However, according to Khoury, there are right and wrong ways to help those struggling. Toxic positivity is defined as minimizing a person’s emotions and telling them that they can simply “will” away their issues. This line of support can cause much more harm than good.

“Saying things like ‘It’s not that bad’ or ‘just be positive! It’s not that hard’ can make someone feel like what they feel isn’t important, and that their struggling mental health is their fault,” Wellness Club president Megan Rabaut ’21 said.

Co-Presidents of Wellness Club Sophie Hugh ’21 and Rabaut agree that there are many resources available for students who are looking for help with their mental health- they can reach out to counselors, teachers or any trusted adult. However, it is important that these people understand the impact of their words.

“If students start to feel that everyone is on the same page except for them, they will start to compare themselves to others or overthink and snowball into negativity,” Hugh said.

If someone who is struggling comes to you for help, the first step you should take is ask them what you can do to help, or how can you support them in the present rather than trying to outright solve their problems and “fix” them, according to Khoury.

“I think really the only unhelpful thing a person can do would be to minimize a person’s feelings,” Khoury said. “When someone is reaching out to you they are sharing their perspective and struggles.”

According to Rabaut, one of the biggest negative effects of toxic positivity is that a person is much less likely to reach out for help following an experience with this toxicity.

“Most importantly, (toxic positivity) can show someone you don’t care about what they feel, which is horrible for someone feeling this way,” Rabaut said. “This can make people suffering spiral and severely worsen their mental health. We need to think before we speak or post.”

The best thing you can do in a situation in which someone comes to you for help to avoid being overly positive and risk further hurting the person is to be honest, according to Kerrigan Dunham ’21.

“Try to be their third party guidance, and help them find the best path to achieve what they want,” Dunham said. “Avoid lying to make someone feel better because it almost always ends up having adverse effects.”

According to Hugh, most barriers for students trying to get support for their mental health struggles are self-built. She emphasized that it is totally normal to be afraid of the reactions of others when they reach out for help.

“Depending on the student’s home life they can be more or less welcome to help,” Hugh said. “If their parents never expect them to ask for help, they may not when it comes to their mental health.”

Khoury emphasized that the mental health team at South, comprised of her and the counselors are available to everyone. She said that all students should feel comfortable coming to them for assistance, or can view the aid resources on their mental health website.

“I think that some students don’t self refer for many reasons,” Khoury said. “I feel that every person’s situation is a little different. Sometimes mental health is not talked about or valued in some homes. Again, my hope is that all students reach out for help if they need it.”

Ultimately, according to Dunham, it is important to recognize what toxic positivity looks, sounds, and feels like in order to be the best ally possible to those struggling with their mental health.

“I think a lot of the ‘resources’ provided (for those struggling) don’t see any effect unless put into action,” Dunham said. “Positivity starts with us, and then if done right, continues outward.”