*Source’s names have been changed to protect identity.

By Hannah Connors ’16 | Copy Editor

Making herself throw up four times a day was not how Sally* envisioned spending spring break last year. But thanks to her eating disorder, that’s exactly what happened.

Sally’s struggles are common. Twenty million women and 10 million men in the United States suffer from a clinically-significant eating disorder at some point in their life, according to the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA).

There are three main types of eating disorders. The first is anorexia nervosa, which involves inadequate food intake resulting in a weight that is too low. Bulimia nervosa is a disorder where consuming food is followed by self-induced vomiting, also known as purging. Finally, binge eating disorder entails eating very large amounts of food, past the point of hunger, along with strong feelings of shame or guilt, according to NEDA.

Sally said she was bulimic.

“I started losing weight in a healthy way. Then when I went on vacation in February, I ate burgers with my family, and I felt like sh*t because I’d been eating so healthy,” Sally said. “I made myself puke. I told myself ‘that’s really bad, stop, that’s not who you are, don’t do this.’”

Sally originally thought that her first instance would be the last, but upon arriving home, it became a pattern, she said.

“I went on spring break, and I did it four times a day,” Sally said. “After every meal I’d just go. It was an automatic thing. That’s when I felt like it was controlling me.”

Eating disorders are mental illnesses, South psychologist Scott Bruns said.

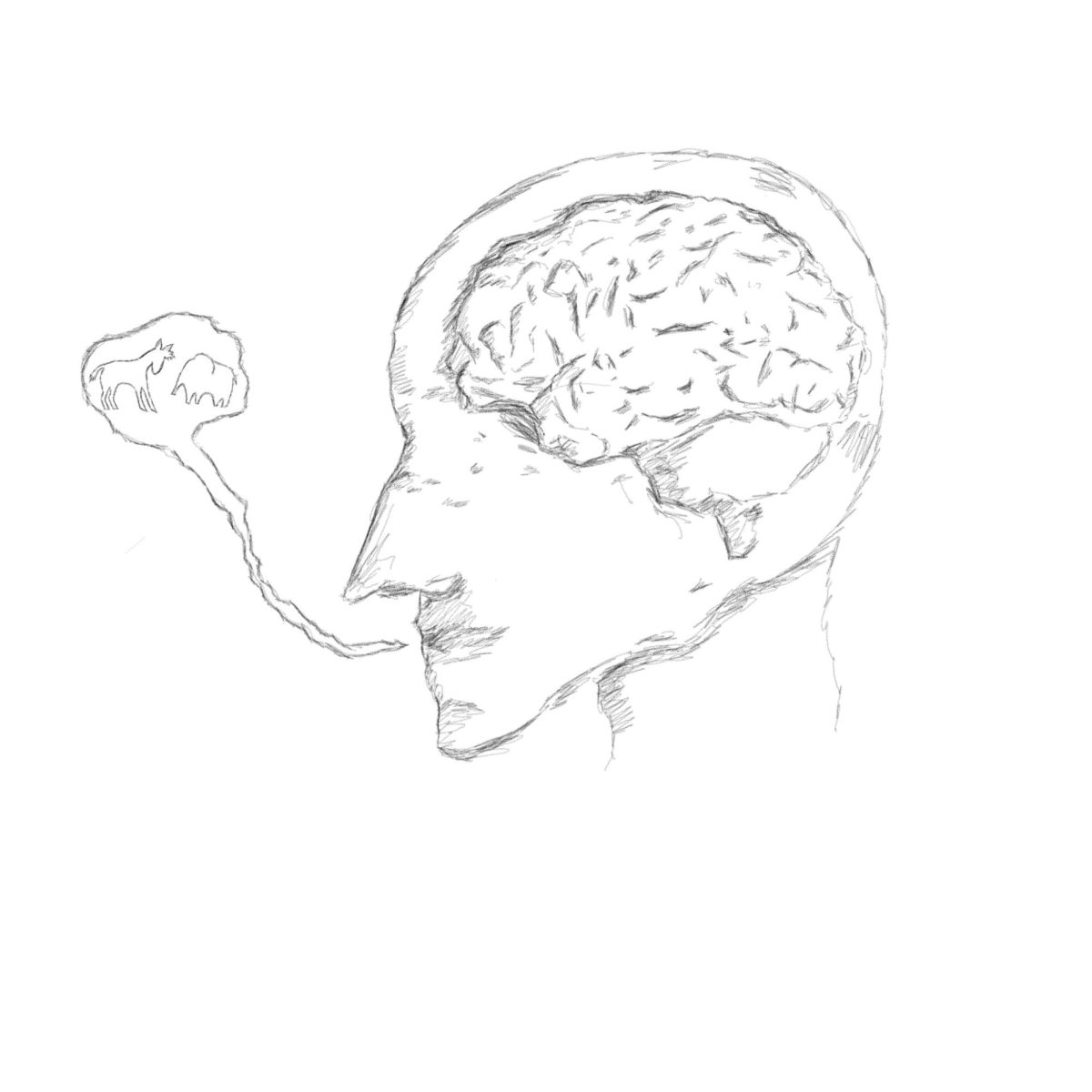

“You’re dealing not just with behaviors, but with thought processes,” Bruns said. “They can weigh 80 pounds and think they’re too fat. It’s a matter of complete misperception on their part.”

This misperception is called body dysmorphism, pediatrician Laura Clark said via e-mail.

“Body dysmorphism is the feeling that oneself is overweight or overestimating body size or shape,” Clark said.

Sally was unhappy with how her body looked, she said.

“Some of my friends started losing weight, and it made me want to, too,” Sally said. “Once I started purging, I was so afraid to put the weight back on.”

While body image may seem like a significant trigger for eating disorders, they are primarily caused by genetics, Bruns said.

This was true for John ‘16*, whose family has a history of depression, he said. Ultimately his depression led to his anorexia.

“I was angry with myself, but I also felt so bad for myself,” John said. “I thought the only way to cope with it was to not eat.”

John said he started eating progressively less until he was skipping meals altogether.

“I never felt hungry. I never felt anything. I had no emotions. I was numb,” John said. “What hurt me the most was not having emotions.”

Depression prompted feelings of emptiness and worthlessness, John said, that reduced his appetite to the point of anorexia.

“I thought not eating would help me mentally,” John said. “I felt empty with all my friends. I thought I wasn’t doing enough and I wasn’t liked enough. Even if I had good grades, even with my family, that’s how I always felt.”

Although 50 percent of males concerned with weight in a study conducted by the Journal of the American Medical Association were worried only about gaining more muscle, 10 – 15 percent of those with an eating disorder are male, according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD). However, John said his disorder developed before he felt societal pressure to gain weight.

“Considering that most of my problems with eating were in middle school, there wasn’t any pressure to be muscular. I don’t think anybody cared about that. I was definitely ashamed to talk about the fact that I wouldn’t eat because I never felt I could control it,” John said. “I didn’t think people would understand it from my point because maybe they thought I would have done that for the same reasons a girl at my age would have, when really I didn’t eat because I wasn’t happy.”

Prompted by shame, John said he took an independent approach to recovery at first.

“I wouldn’t even talk with my parents. Depression is something that runs in my family, but it was very difficult for me to talk even with those who had struggled too,” John said. “Sometimes I would look stuff up and try to figure out what I could do to help myself, but it was just me trying to do my own thing.”

John became dangerously underweight during this time period, and participating in sports became more difficult, he said.

Sally, who also participated in sports while she was struggling with her eating disorder, underwent both physical and emotional changes, she said.

“I was always freezing, and I had no energy, ever,” Sally said. “After I made myself throw up, I just wanted to sleep for 12 hours. I was always in a bad mood.”

Other effects of eating disorders include dry skin, slow growth or loss of hair on scalp, loss of menstrual cycles, constipation, abnormal electrolyte levels and slow heart rate.

Psychological changes can occur as well, Clark said.

“Many of the patients I have seen with excessive weight loss due to anorexia are often described by their family as irritable, and once they start gaining weight and are no longer in starvation mode, their mood improves,” Clark said. “This malnutrition truly affects the brain function.”

In addition to Sally’s chronic bad mood, she was physically ill, she said.

“It got to a point where it (purging) caused something in my body to become really messed up. I couldn’t go to the bathroom, and I was in so much pain,” Sally said. “I had no nutrients in my body.”

In extreme cases, people with eating disorders can make themselves so weak they need to be hospitalized, Bruns said.

Eating disorders can also lead to changes in the heart in the long term, Clark said.

“With improved nutrition and weight the heart rate and blood pressure will improve, but if there is significant long-term malnutrition, the heart is more prone to arrhythmias causing death,” Clark said.

Because of these life-altering effects, it is important for people who are struggling with eating disorders to reach out for help, Clark said.

While Sally didn’t tell anyone at first, eventually her friend William ‘16* found out what she was going through, she said.

“We ate dinner, and then I went in the bathroom and made myself throw up. He said, “You were in there for 20 minutes. What’s going on?” This was also when I was getting sick, so I was freaking out, and I had to tell someone. I couldn’t do this on my own,” Sally said.

In addition to Sally being in the bathroom for extended periods of time after meals, William knew something was wrong due to a change in Sally’s demeanor, he said.

“She would seem randomly upset sometimes and look almost as if she’d been crying,” William said.

Upon finding out, William was worried and wanted to help in any way possible, he said.

“I agreed not to tell anyone as long as it got better, but over time I couldn’t do enough to help her, so we had to tell someone. I was scared she could do permanent damage,” William said.

William texted Sally’s mom and told her about the eating disorder, Sally said.

“We were in a class together and he (William) wouldn’t talk to me, and I didn’t know why,” Sally said. “All of a sudden I got a text from my mom that said, ‘I’m calling you out of school.’ He told my mom everything I’d been doing.”

While Sally was upset with William for telling her mom, she knew he did it because he cared about her, she said.

“I did it because it’s awful to see someone go through something like an eating disorder, especially when you care about them. I knew she didn’t need that in her life, and it was only going to get worse, so I wanted to stop it as quickly as possible,” William said.

Sally’s mom was freaked out when she first learned about the eating disorder, Sally said.

“The first week after she found out was really bad, she was on me like a hawk after every meal,” Sally said.

After Sally’s mom told Sally what can happen to your body over the years if you have an eating disorder, she realized she needed to stop, Sally said.

“She was really real with me. She said, ‘Do you know how bad this is for your body?’” Sally said.

John’s parents also found out about his eating disorder without him telling them. One of his friend’s parents found out, and then told his parents, John said.

“I was embarrassed to look my family in the eye and tell them,” John said.

If someone thinks their friend may have an eating disorder, they should confront them, Bruns said.

“They’re probably going to deny it and step up the efforts to hide it. But it shows them you care,” Bruns said.

While many people struggling will attempt to hide it, others don’t even acknowledge their disease. Most of Clark’s patients will not come out and tell her they have an eating disorder, because they do not see anything wrong with what they’re doing, Clark said.

“It often is not until I bring it to their attention or their parents bring them in to discuss it that they start to realize that they have a disorder–they don’t see themselves as too thin and most times are very upset that I suggest that they gain weight,” Clark said.

The next step after determining a patient has an eating disorder is to refer them to a dietician to develop a meal plan, and a therapist to deal with the psychological aspect of the disease, Clark said.

“I often will have the patient come into the office every week or two to check weight to make sure they are progressing as expected. If the patient is not gaining weight or continues to lose weight, I may need to refer them to a specific eating disorders program or even hospitalization,” Clark said.

Someone with an eating disorder should seek professional counseling, Bruns said.

“You need to do more than talk to your parents,” Bruns said. “It’s a very resilient disorder, in the fact that it’s very hard to treat.”

John sought help from family friends with careers as therapists, but never experienced official treatment. However, he said he is recovering.

“In the last year I’ve gained 20 pounds, which was my goal,” John said. “It’s still hard for me to eat lunch sometimes, because I’m not hungry anymore; I used to not eat at all. I’m still not up to what people who eat every day at every meal experience. My family knows I struggle to eat, so they always make food for me.”

John cited his friends as his main support systems as he recovers.

“No matter what, there are always going to be people who are there for you,” John said. “Never be ashamed to go to them.”

Sally also overcame her disorder, she said.

“I still get tempted to do it (purge). I eat healthy, so on the weekends if I pig out with my friends, I feel disgusting and I want to do it,” Sally said. “But it’s not going to help me.”

Learning how to deal with body image was key to beating her disorder, Sally said.

Sally said, “High school guys want the girl with the perfect body, and a lot of us girls strive to be it. But God made me the way I am, and whether I’m five pounds lighter or five pounds heavier, I am accepting it.”