It Will Rise from the Ashes

Remembering the 50th anniversary of the '67 Detroit Riots

May 31, 2017

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. At its economic height, the city of Detroit in 1967 boasted a population of nearly 2 million people and a powerhouse of an auto industry that served as the city’s backbone. Simultaneously, racial tension continued to broil just underneath the surface of the city, eventually erupting into what would be known today as the ‘67 Detroit Riots.

BEFORE THE RIOTS

Detroit resident Ee. Jean Matthews was just 15 when she came to Detroit. She remembers the feeling of wide-eyed wonder upon seeing the city for the first time.

“It was huge!” she said, recalling what it was like to move to Detroit from her small town in Arkansas. “It was a lot cleaner than it is now. People as a whole kept their property up. They were proud of what they had. And it was a lot of fun going downtown. There were lots of people downtown.”

Matthews remembered being able to enjoy all different types of leisurely activities with her friends as a young woman in Detroit.

“We went to Belle Island,” Matthews said. “We fished. We went to the movies. We went to the hamburger joint. That type of thing.”

At the same time, however, Matthews still said she could feel the daily constraints of racism weighing down every aspect of her life.

“(It was) every single day,” Matthews said. “White people lived with white people. The majority of the stores were owned by white people.”

Out of all the many instances in which she personally experienced racism first-hand, one moment still pains her.

“One time in particular,” Matthews said. “And I was an adult, probably 30, and two young white boys asked me was I selling anything, asked me if I was a prostitute. It angered me. I got very angry. And it didn’t make me feel good at all. I had just left work, and it was very funny to them. They laughed a lot about it.”

Despite the continued racial barriers that structured everyday life for Matthews, she didn’t expect the riots to happen.

“I was surprised that about the race riots,” Matthews said. “I was busy raising a family, and when you’re doing lots of other stuff, sometimes you’re not aware of what’s going on around you. You’re busy trying to make a living, and trying to take care of your children.”

At the time, Matthews lived three blocks from 12th and Clairmount.

12th and Clairmount also happens to be where, on a sweltering day on Sunday, July 23, a police raid on a community celebration inflamed into a full-fledged riot, the epicenter of week-long upsurge of violence and chaos.

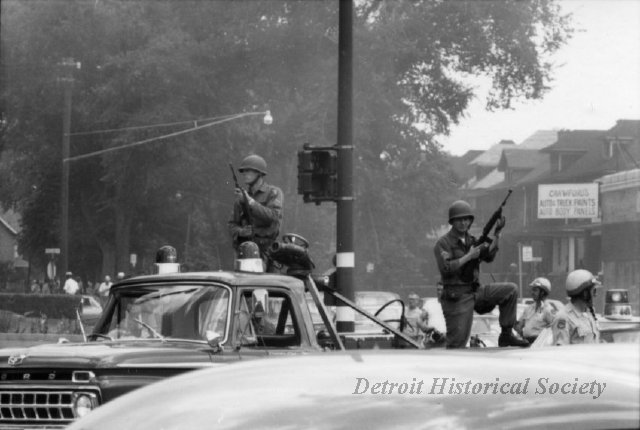

“I was scared. I was very frightened,” Matthews said. “Things were burning and people were making loud noises. The National Guard was driving down the street in tanks. So you can imagine how frightening that was.”

Over the next five days, the city would engage in a conflict between civilians and police, including the Detroit police and fire department, the Michigan State Police, the Michigan National Guard, and eventually the United States Army, according the the Detroit Historical Society. The aftermath of this war-like ordeal left Detroit to deal with 1,700 fires, 43 deaths and over 7,000 arrests. To this day, the 1967 Detroit Riots are the third most costly riots, with the Chicago Tribune recording the total cost of damages to be $293 million.

“For a long time, it didn’t change,” Matthews said. “For a long time, things were burnt and things were awful. Then you read lots about it, and sometimes when you’re reading about things, it feels like it’s happening all over again. The riots only made the police meaner. It made them meaner.”

WHAT CAUSED THE RIOTS

Over the years, the violent, destructive event that unfolded in the summer of ‘67 in Detroit has been given numerous names. Some refer to it as a riot. Some, a rebellion. Others, a civil disturbance. For Greg Bowens, President of the Grosse Pointe-Harper Woods Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the labels people give to this moment in history depends on their perspective.

“The perspectives that people may have on history is always viewed from where they stand, and the lens that they view it from themselves,” Bowens said.

Bowens refers to the riots as a rebellion.

“We do that because it encompasses all of the public policies that were put into place that prevented people of color from living where they wanted to live, from working where they wanted to work, from being full participants in the economy at the time,” Bowens said.

At the time, Detroit’s thriving auto industry created a land of milk and honey for Americans, black and white alike, attracting workers from Southern states up to the growing city. As a result, competition for jobs and property left most minorities out due to discriminatory laws, creating a rift in the city along racial and socioeconomic lines.

Bowens said in order to understand the racial tensions existent in Detroit during the 1960s, it is important to first look far before the riots, back to the time of Reconstruction and the birth of Jim Crow laws.

“What made slavery so different was that we as Americans have codified slavery specifically based on race, meaning that you can be born into slavery simply based on the color of your skin,” Bowens said.

By the time the Civil Rights Act of 1964 came into effect, Bowens described this decade as watershed years in terms of breaking down the barriers still lingering from the era of slavery. Even still, America was dominated by bigotry.

“By the time ‘67 had rolled around, the last vestiges of Jim Crow were hanging on, it was still almost impossible, extremely difficult for people who wanted to be able to get a loan, buy a house, work as a police officer, to get hired because the generation that was still in charge, the children and the grandchildren of the people who had grown up with with kind of privilege,” Bowens said. “And so they were willing to change, and times were slowly changing, but they weren’t changing fast enough in order for people to have decent houses. It just didn’t happen.”

This slow progress is the exactly the kind of social strife Matthews had to endure, she said.

Matthews lived during a time where she couldn’t live where she wanted nor work where she wanted. She lived in a world where she said that if she had went to the hospital because her baby was sick and hurt, it wasn’t guaranteed they would even treat her child.

“Things were different then, and they didn’t guarantee whether you would get treated or whether you would get service or not,” Matthews said.

Bowens said not only did these discriminatory practices exist in employment, but housing as well.

“There’s nothing fair about building a new subdivision and all the things that come with it, the new roads, the latest appliances, loans from banks, and excluding minorities from it,” Bowens said.

In an effort to keep communities segregated, organizations such as the Homeowner’s Association fought against the integration of schools and neighborhoods by building suburban communities to keep minorities out, according to The Detroit Historical Society. Champions of these policies included former mayors Louis Miriani and Albert Cobo. In addition, the city continued to discount minority residents of Detroit.

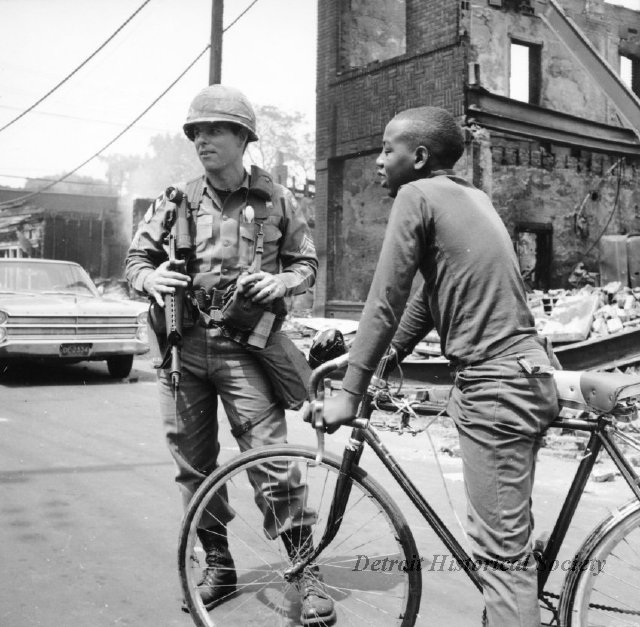

A young Detroit resident with an armed sergeant from the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division on the intersection of Westminster and Goodwin Streets.

Two of Detroit’s major black neighborhoods, namely Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, were destroyed to make way for freeways and new suburban neighborhoods that would continue to bar black residents.

On top of prejudiced housing and employment policies, discriminatory policing instilled fear and anger in the hearts of black residents in the city. Though he was only six at the time, Detroit resident and Mt. Pleasant Missionary Baptist church choir director Anthony Flournoy remembers feeling the anger and fear of the adults around him at the time of the riots.

“And there was a lot of anger, even seeing how the police treated black people back then,” Flournoy said. “They had a group called the Big Four and they also had a group called STRESS (Stop The Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), and people, as you see sometimes in the news today about unarmed black people being shot for no reason, people were similarly being treated as second class citizens.”

After the riots, the Detroit Police Department organized the special task force STRESS with the purpose of controlling the unrest built up from the riots. According to the Detroit Historical Society, the force only further agitated the relationship between civilians and the police, which was accused of racially targeting black Detroit residents.

“People were just upset and frustrated by how they have been treated, been ignored, been discounted, been talked to any kind of way just because of, for lack of a better term, racial profiling. And it just erupted from there into violence,” Flournoy said.

Flournoy said he still remembers seeing the smoke billowing over the east side of the city from his view on the west side of Detroit. As a child, however, he couldn’t quite understand what was going on, but he said he could feel the anger and fear emanating from his parents.

“You could feel a lot of tension in the neighborhood, you heard adults talking about things, you could see the smoke, and everything was on the news. The riots dominated the news. Even in church, people were telling others, ‘Just stay calm, keep your kids at home.’ That was the main thing. You couldn’t go anywhere.”

Flournoy has two older brothers. One was 17 at the time at the riots and the other was 19 and serving in Vietnam. Flournoy said his parents were so worried for his 17-year-old brother that they would drive him to and from school to make sure he was safe.

“At six, I couldn’t go anywhere anyway. I was just at home playing,” Flournoy said. “But you could feel the tension. You could see police just everywhere, driving around the neighborhoods. And at six, I didn’t know exactly what was going on. But you saw the smoke and you ask questions. And my parents were moreso concerned about my brothers and cousins. People were just nervous, they were wondering how far it would go.”

ANATOMY OF A RIOT

In the dissection of a riot, socio-economic, historical, cultural and racial factors are taken into account.

The most costly civil disturbance in American history was the Los Angeles riot of 1992, with an estimated $1.3 billion in damage according to The Chicago Tribune, was initially a response to the acquittal of a police officer accused of beating of a black L.A. resident.

In Detroit in 1967, there was no single death. No single acquittal that triggered the onslaught of millions of damage and deaths of many Detroiters. It was the accumulation of decades of social rifts caused by socioeconomic and racial discrimination, Bowens said.

When it comes to looking at the dynamics of a riot, Bowens said it’s a matter of perspective from a historical standpoint.

“It’s a matter of perspective, and one of the things that we have to be honest about when we talk about our shared American history is that it is a shared American history, and that we can admit that some of the things that we have done wrong as a society without having to feel the guilt about it today,” Bowens said.

Thinking back to the horrors of the riots, Matthews simply described riots as a way for those who feel trapped to express themselves.

“I don’t think that people should be fighting, but sometimes there is nothing else that you can do,” Matthews said. “And when there’s nothing else that you can do, then you have to fight.”

Flournoy said the path to understanding the complexities of a riot requires understanding the perspective of those rioting.

“People riot because they feel hopeless, they feel powerless,” Flournoy said. “(They’re) saying, ‘You’re not hearing me right now, so I’m going to make you hear me.’ And through rioting, sometimes the message is lost. Unfortunately in rioting, they’re just going to see the ‘what,’ and they’re not going to see the ‘why.’”

AFTERMATH

Bowens was just two-years-old when the riots happened.

“I was too young to really remember firsthand what things looked like . . . people will remember how you made them feel, they will remember what things felt like, more than what they heard and what they saw,” Bowens said. “Feeling seems to be a more accurate place to start when you go back to memories.”

He described his generation as the first one to be born after the Civil Rights Act, but even still he was brought up with the perpetual fear that things haven’t changed after all.

“Yes, we could get on I-75 and drive down south to visit relatives and stay at any hotel we wanted to, but our parents, who had grown up knowing that there were some places that you couldn’t stop and that there were some things that could happen to you on the road where you could be killed, they still had a wary eye,” Bowens said. “So since they were raising us, they were raising us to survive in a segregated world which by law had ended, but by practice was still dying out. There was still a certain level of fear that there were things that you could and could not do.”

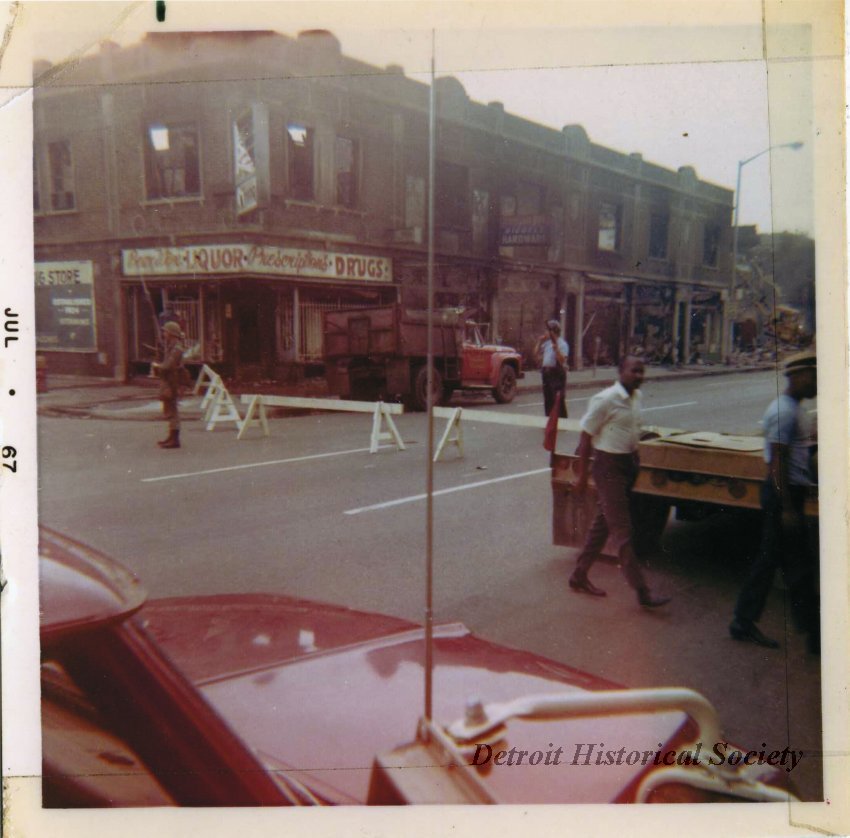

Wooden barricades separate 12th street, the epicenter of the riots.

Growing up, Flournoy said his innocence was saved from the horrors of the riots.

“(Adults) did a great job trying to shield kids from certain things they didn’t want us to hear. They would send us outside when the news was on so we couldn’t see the violence, but you could see the smoke again outside,” Flournoy said.

After the riots, Flournoy said he saw the considerable population of white residents gradually migrating out of Detroit.

In addition to the riots, most white Detroit residents were moving out to newer suburban areas of Michigan. According to the Detroit Historical Society, Detroit saw a decline in nearly 20 percent of its population between 1950 and 1960.

“That’s really what started the downturn of the way Detroit looked, because homeowners take better care of their property, not always, but most homeowners care more,” Flournoy said. “But when the people started leaving the houses in droves and renting out their houses, they didn’t care as much, so then you started seeing a lot houses being boarded up and abandoned. That really started the downward spiral of how the neighborhoods looked. And then drugs started coming in soon after that and it just escalated.”

Although Detroit was being shattered into pieces both economically and racially, a glimmer of optimism rose from the ashes of the riot’s wreckage. To many Detroiters, the election of Coleman Young, the first black mayor of Detroit, brought a new sense of hope, Bowens said.

“By the time I was a little boy, Coleman Young had become the first black mayor of Detroit, and even though I wasn’t old enough to vote . . . but I felt the sense of pride and accomplishment and hopefulness that my parents and grandparents felt, so I felt good, and didn’t really know why,” Bowens said. “So by the time I was in high school, I was used to feeling comfortable with going where I wanted to go, I had a black mayor, I saw black police officers.”

During his term as mayor, Young would not only bring hope to some Detroit residents, but dismantle many of its discriminatory policies, such as the police force STRESS, alleviating many of the fears felt by the black community toward police.

“He brought hope and a face to let people know that someone actually listens to us,” Flournoy said.

Flournoy equated the feeling of Coleman Young getting elected to the election of former President Barack Obama.

“I felt similarly when President Obama was elected. I felt like the poem from Maya Angelou ‘And Still I Rise.’ I never thought that I would see that in my lifetime. And for it to happen it was like — and you couldn’t really express it,” Flournoy said. “The same feeling went for the first black mayor of a large city. So that was a feeling of pride, a feeling that things are finally getting better.”

Bowens said this pattern of progress would continue into the future, and that future generations of children would only have their parent’s emotions to understand the complexities of what was really going on in society.

“By the time I was in high school, it was the 80s and it was New Wave, and everybody was ‘cool,’and people were dancing together, and it was different. My parents, they still had this skepticism because they remember friends who had been killed because of racists,” Bowens said. “It used to be like this: there used to be this saying that there is ‘no law that any white man had to respect with respect to a black man’. It took a long time for things like that to change.”

FROM THE ASHES

As history fades into the folded pages of the textbooks, Bowens says there are those in the community who would simply forget the riots; dismissing them as a barbaric time.

“There are people who don’t want to remember the ‘67 Riots. They think it’s a black eye on our city, they think that with all the growth that is happening in Detroit right now, having this discussion about the ‘67 riots would be bad for growth and put the city in a bad light,” Bowens said. “A better way to look at it is that as we mark this anniversary of the riots, we have the opportunity as a society to pick your place, to remember things that created segregation, that created these unequal conditions so that we don’t repeat it.”

Bowens does not see the riots as some kind of societal plague to be wiped from the record, but as a stepping stone from which to pave the way to a bright, bold future for the youth of the country, who have been so wronged.

“It’s not some kid’s fault who was born in 1998 that the country had discriminatory housing policies,” Bowens said. “We live in a better society because we’ve learned to treat each other with dignity and respect, and we’ve found the value of human life.”

The value of human life, Bowen says. It means different things to different people, but for many of the denizens of Detroit during the riots, it has increased tremendously.

Particularly for Flournoy, who sees a new Detroit climbing from its self-dug grave in favor of a bubbly, bright atmosphere, riddled with gentrification and reconstruction.

“The shape of Detroit is what we see as we look across the whole city,” Flournoy said. “A lot of abandonment and a lot of vacant neighborhoods… that started as a result of the riots. Now we’re starting to see a lot of that getting rebuilt. The sad thing is that a lot of people who were here, some people who are still here won’t be able to afford to come back or to move into the areas that they’re building up, because the prices are going to be so much greater.”

Above all else, in the face of such rapid reassembly, harkening back to the days of the churning fires of industry, Flournoy informs the citizens of the United States that there is one human component which must not be lost above all else.

“As Detroit is shifting back to perhaps a more predominantly white city, you don’t want to start treating people as outsiders, especially people who’ve been in Detroit this whole time, whether they’re black or white,” Flournoy said. “You don’t want them to feel like they’re not a part of this process. This should be process where everyone has something to gain and something to contribute, and don’t eliminate anyone just because of the color of their skin or their socioeconomic status.”

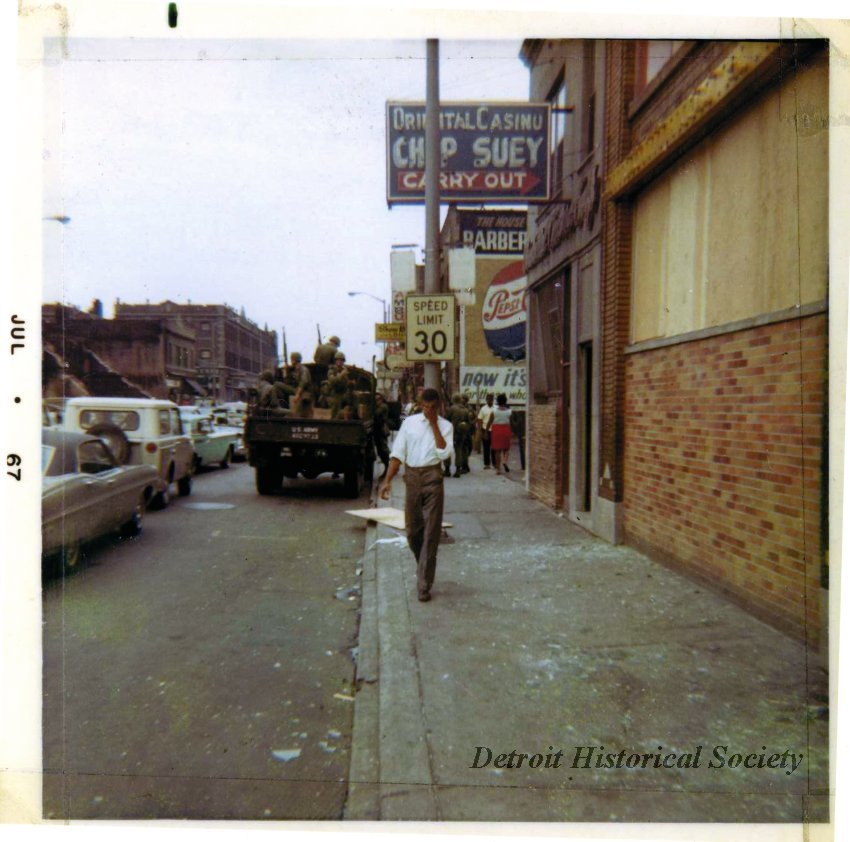

Detroit resident walking away from the chaos of a riot. The riots lasted five days, with damages estimated to be as high as $294 million, according to the Chicago Tribune.

[Special thanks to the Detroit Historical Society for providing The Tower Newspaper with their archives]