Keepin’ it black and white

February 12, 2020

Representation takes many forms: from who is on a TV screen, to the makeup of the government, to local leadership, the identities built into daily life can greatly affect the way a society functions. Suburban organizer for the Michigan Roundtable for Diversity and Inclusion Dez Squire said lack of diversity, and therefore lack of representation, is detrimental to the ways a community can become more inclusive.

South has a 15 percent racial minority population, according to U.S. News and World Report.

So what does it feel like to be part of that 15 percent?

11 Grosse Pointe Blvd.

“It’s like being on an island,” social studies teacher MaShanta Ashmon said. “It’s like me being on an island alone.”

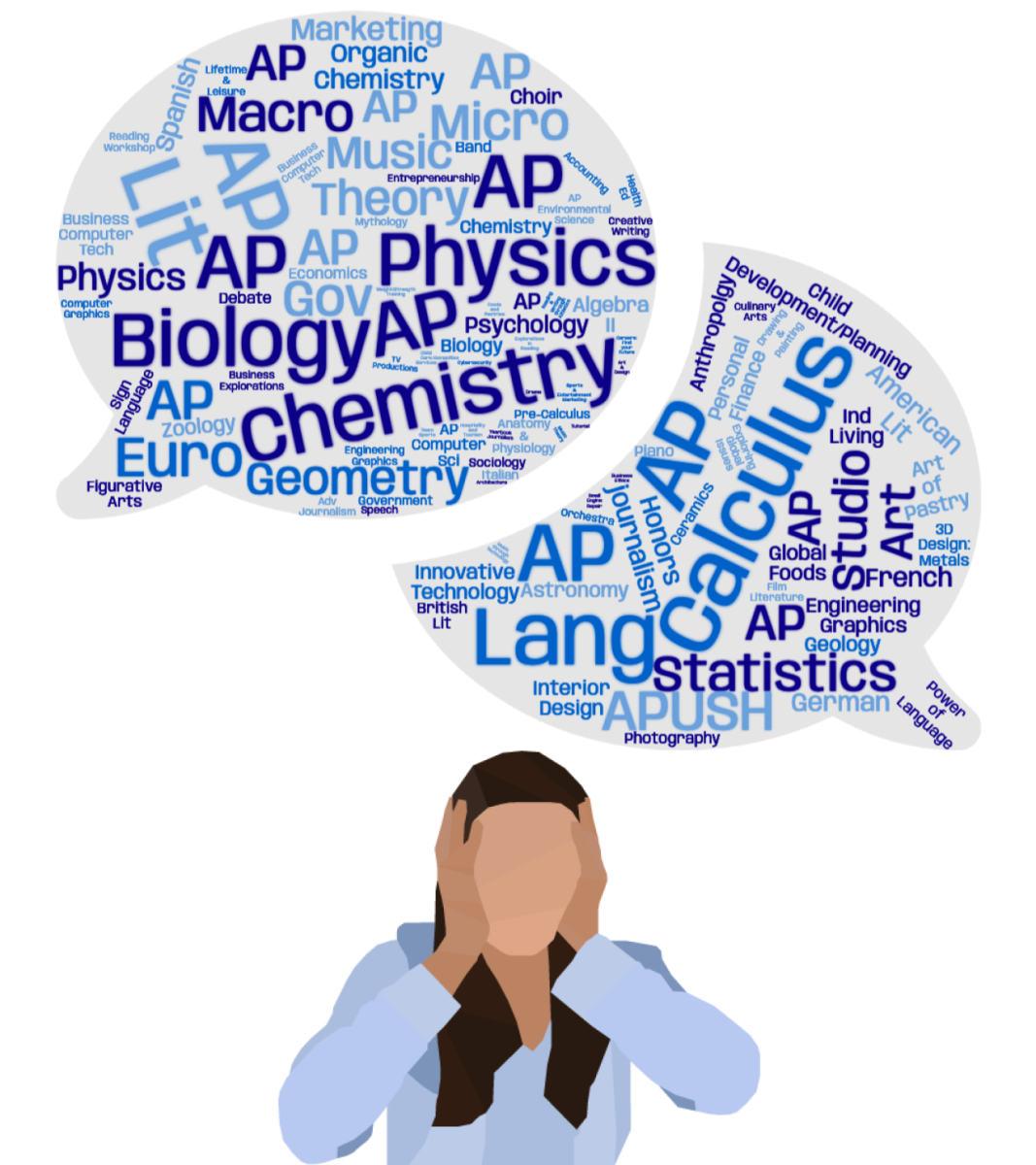

Ashmon is South’s only black teacher, and one of two teachers who are racial minorities. She said, because she is some of the only black representation at South, she goes out of her way to be a positive representation of black women and black people in her classroom.

“I know I am the first black teacher many of my students have ever had,” Ashmon said. “In teaching AP U.S. History, what I’ve found is that many of my students have already been shaped by not only their teachers, but their parents, their community and the media. They have an unconscious bias about people, situations and history.”

In order to correct these biases or misconceptions, Ashmon focuses on expanding her curriculum to incorporate diverse viewpoints. But another part of her work as a black teacher is to make students, black and white alike, who have never been taught by a teacher of color comfortable.

“Students who aren’t represented feel disenfranchised,” Ashmon said. “Ironically, I think when students of color end up with a teacher like me, a woman of color, they’re a little bit uncomfortable or uneasy. They haven’t had the experience before. I think they shy away from me because it’s still uncomfortable and something unusual to them. If there was more representation in their lives, this wouldn’t be the case.”

Principal Moussa Hamka, who is Muslim and of Arab descent, feels like he is “always under the microscope” when doing his job.

“You can’t afford to make a mistake. And if mistakes are made, someone who has a different name or a different skin tone and a different background may be afforded greater grace,” Hamka said. “When you’re within a community that has very low minority representation, the dominant culture can sometimes be unforgiving. And so there’s pressure.”

Zaria Jones ’22 said she doesn’t feel supported at South as a black person. In her 12 years in Grosse Pointe, she has struggled to find people who can relate to her experiences as a minority. When she was younger, Jones encountered pressure to fit in with the dominant white culture.

“There’s a lack of my culture here,” Jones said. “It’s hard to grow up without many people (who are) my race. In middle school, there would even be black students who went against our race to fit in.”

Jacquelyn Wang ’21 has never had a teacher of color, much less a teacher that looked like her. Teachers and other students do not know how to approach the topic of race around her, according to Wang.

“If we were reading passages by Asian authors, and there would be Asian words or phrases, the class would turn to me,” Wang said. “They wouldn’t want to offend me or say something wrong. You feel like an outsider.”

Black students are 32 percent more likely to enroll in college if they have two black teachers by third grade, according to a 2018 study published by Johns Hopkins University.

Being an unapologetically black teacher is important to Ashmon. She won’t “assimilate” to fit into Grosse Pointe because it is other people’s responsibility to learn, grow and question what they see.

“I’m very proud of who I am,” Ashmon said. “Students say, ‘Why do you represent yourself as a black woman, why aren’t you just a woman?’ But if you don’t see me as a black woman, then you’re not seeing me. Because we are different. And that’s not a bad thing.”

In the lens

Twenty percent of lead actors in theatrical films in 2019 were people of color, according to a recent study published by UCLA.

When she was younger, Wang said she never felt represented by the people she saw on her television. She saw very few strong, Asian role models.

“Seeing Princess Mulan in a movie was a huge moment for me,” Wang said. “That was the first time I saw a strong, Asian woman in mass media because Asian women are always portrayed as small or weak. She showed me I could do more.”

Recently, there has been a monumental shift in representation, according to Hamka. His elementary-aged daughters are able to see people who look like them in their daily lives.

“As a kid, I did not see many authors who were Arab or Muslim. There weren’t many story books about me,” Hamka said. “But for my kids, their experience is so much different. There are books in their school about a girl putting on the hijab. There are cartoons on PBS where they visit Muslim countries and experience Ramadan.”

There is still plenty of room for improvement when it comes to diversity in the entertainment industry, according to Hamka. Too often, minority voices are not heard— even when the issue is directly concerning them.

“I would love to turn on Fox News or CNN and see more voices of people whose names sound like mine,” Hamka said. “It baffles me when we get experts on the news or television to speak on a topic when they are not from the group we are discussing.”

Ashmon has encountered many instances in which the lack of diversity in the media, particularly cable news, has led to negative results. She believes integrating major networks would significantly lower the racist incidents created in the newsroom.

“BBC put up a picture of LeBron James, instead of Kobe Bryant, (in their tribute segment) as if all black people look alike,” Ashmon said. “If there was more representation in the media, then something like this wouldn’t happen. We need to be represented, worldwide, in different avenues.”

When mass media only shows one side of a story, Ashmon said it systematically dehumanizes an entire community and it impacts how the criminal justice system responds to black and brown people.

“Oftentimes, African Americans aren’t represented in the media in a positive light. So you either see the superstar, or you see the criminal, and that’s it. There’s no in between for a lot of people,” Ashmon said. “We’re actually tried and convicted in the media before we even step into a courtroom.”

1600 Pennsylvania Ave to 389 St. Clair

Twenty two percent of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate are racial or ethnic minorities, the highest percentage in American history, according to the Pew Research Center. However, this is still a 17 percent difference compared to the nation’s minority population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

While the 116th Congress of the United States is the most racially and ethnically diverse in its history, several minority populations are not represented in comparison to their actual populations. Squire said increasing this representation and making it comparable to reality allows for deeper understanding and conversation as laws are made and individuals are affected.

“With each identity, we carry a culture, and that is the lived experience, the stories, the practices and beliefs that come with each of these identities,” Squire said. “When we don’t have a diverse space we don’t have any of those being represented. By not having representation, we begin limiting the solutions we could have and how we look at an issue. We begin limiting ourselves and our communities.”

Ashmon is excited to see expanding diversity in local governments with the recent appointments of Terence Thomas in the Grosse Pointe City Council and Joseph Herd in the Board of Education, both of whom are black.

“I still think we have a lot of room for improvement, but we are making progress. The challenge is going to be: Does this progress keep moving forward?” Hamka said. “We have to be informed citizens and recognize that the progress we’ve made can easily be lost.”

Changing the conversation

While the lack of representation affects people from many different angles, according to Squire, there are ways to combat it systematically. She said the best way to create diverse spaces is to personally reach out to different groups and make individual bonds.

“Relationship-building becomes so important because it is how we create understanding and see how our differences work together or create barriers,” Squire said. “Those relationships are important because they build a collective accountability for creating change.”

Hamka recognizes that his voice carries more weight because of his authority, and there are many community members also focused on creating diverse spaces.

“I’ve been able to promote and advocate for changes in certain areas without having my voice shut down because of my position,” Hamka said. “There are so many great people in Grosse Pointe, and we can’t overlook that. Often times they are overshadowed by the few, loud voices.”

Hamka understands some South students do not see the need to fight for more representation, as they always felt heard. A “deficit mindset,” as Hamka describes, occurs when people believe that giving a minority group a louder voice causes themselves to have less representation. He said this ideology is unfounded and wrong.

“Our community is not monolithic,” Hamka said. “The experiences of our students are on a wide range of spectrums. Some students feel they’re not represented, and others feel they are. These are not mutually exclusive. You can find the right balance where everyone feels represented.”