Huckleberry Finn in the bin

October 11, 2018

Grosse Pointe school district cuts ‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ out of the curriculum and searches for replacement

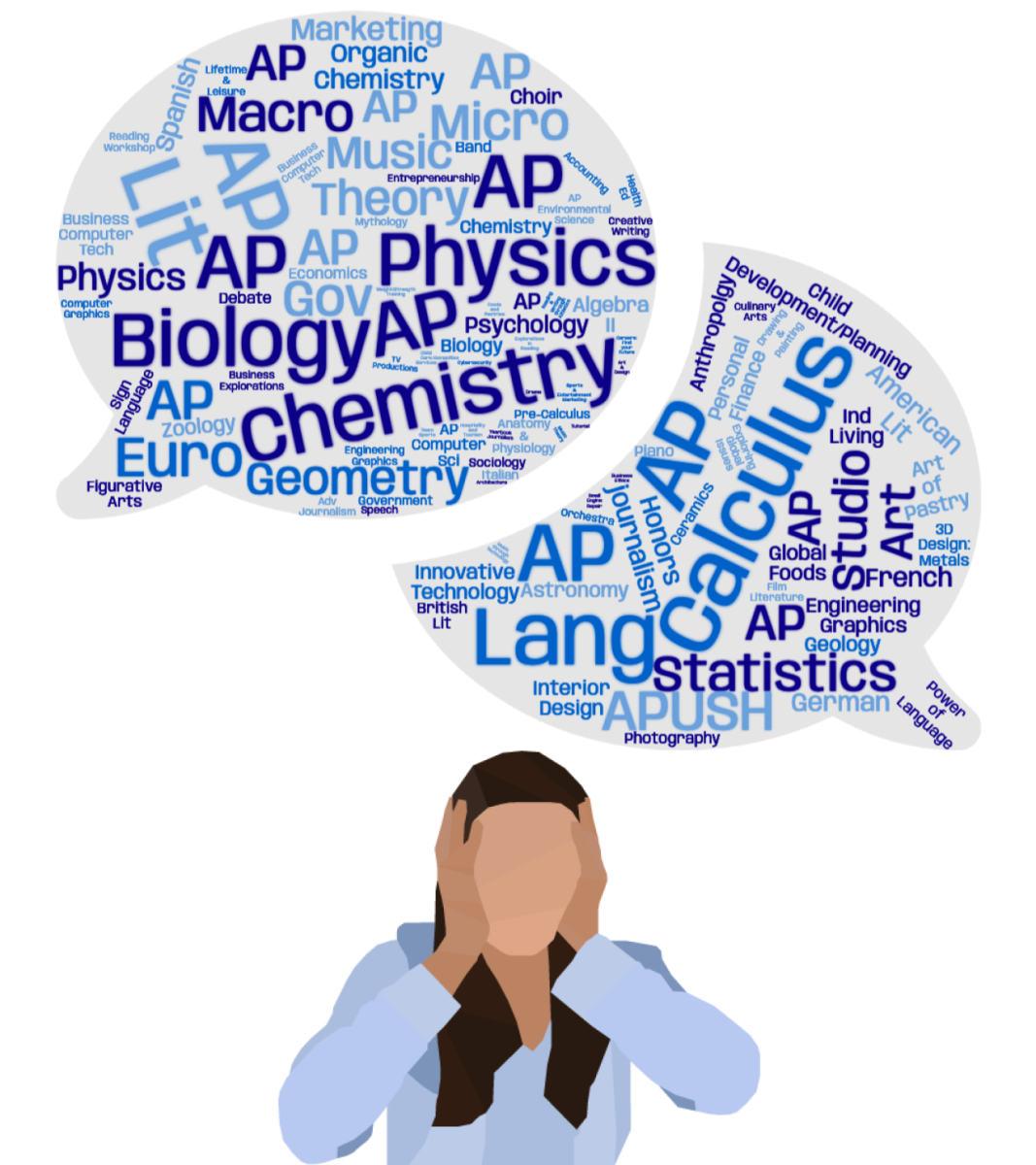

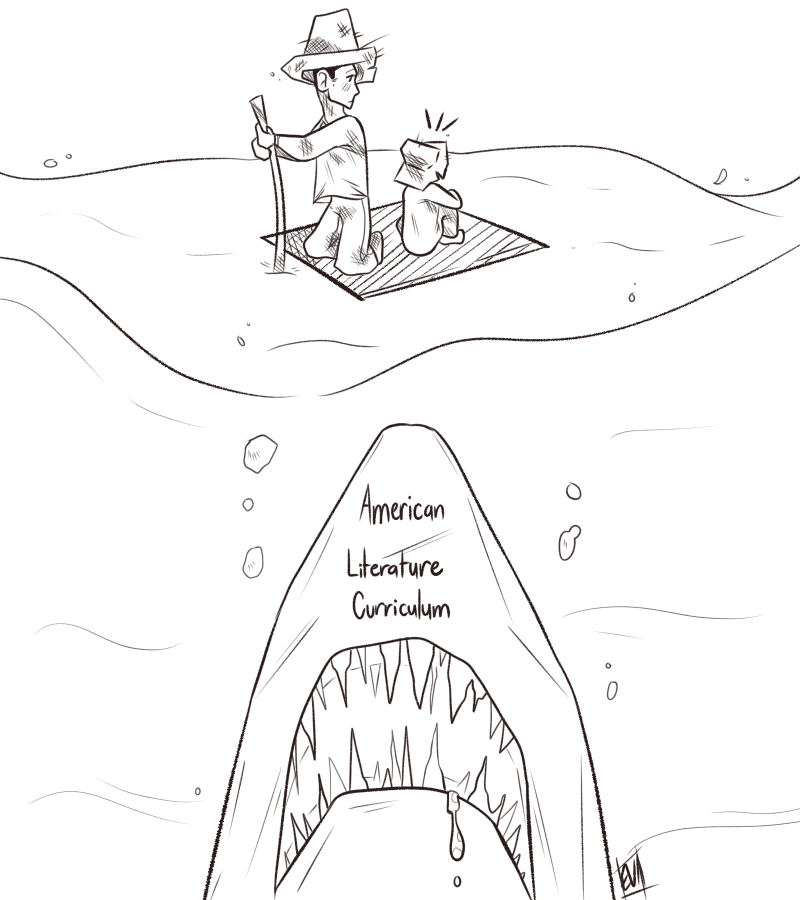

After long consideration, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain was removed from the American Literature Curriculum at South last spring, but no replacement has yet been chosen, according to Curriculum Director Maureen Bur.

Despite an extensive process for the last couple months and a few top picks, no suitable replacement was found, and this year the gap will be filled with a text based unit highlighting diverse voices says Bur.

“Last year the North and South English Departments met as part of a curriculum review to diversify the teaching material to reflect a broader range of literary voice and make sure that our instructional practices are including students of all races, ethnicities, gender and economic status,” Bur said.

When review began last year, it was clear that “Huckleberry Finn” would be one of the pieces in question, as it is one of few books in the curriculum that deals with race, history and representation of minorities, according to South’s English Department Chair Danielle Peck.

“The core curriculum books have been the same for a very long time so we have been thinking about updating the curriculum for a while,” Peck said. “Last year we were given the charge to explore texts that give a more diverse tapestry of America.”

According to Nicholas Provenzano, a former American Literature teacher at South, “Huckleberry Finn” had long been part of a bigger conversation regarding curriculum change at South.

“Conversations like ‘do we still do “Huckleberry Finn,” do we still do “ The Great Gatsby,” do we still do “The Crucible?”’ I would say were always part of a larger conversation about how to improve the curriculum,” Provenzano said. “Never as a separate ‘hey let’s talk about this book, should we still do it?’”

Provenzano said the language used by Twain in “Huckleberry Finn” was one of the major challenges he faced while teaching the book at South.

“Mark Twain wrote this book 150 plus years ago, and the southern dialect that’s used can be very difficult to read and understand,” Provenzano said. “But I think the biggest one is obviously the use of the N-word by Twain in the story.”

“Huckleberry Finn” has been surrounded by controversy both in and out of the classroom, and was banned for the first time in 1885, the same year it was published for its use of the N-word, according to PBS.org.

While discussion surrounding controversy isn’t necessarily a bad thing, sensitive topics like race, derogatory language and misrepresentation based on stereotypes are difficult for many students, according to the North English Department Chairs Kristen Alles and Jonathan Burne.

“Personally, I was glad it was removed,” Burne said. “While it’s an important piece of American literature, I thought it made a lot of our students uncomfortable because of the language in the book and in the way that one of the characters, Jim, is portrayed.”

Alles said that while the book and the discussions with students are valuable, she thinks there’s a better way to teach students about the same issues covered in “Huckleberry Finn.”

“I thought that the mileage we got out of it as teachers wasn’t always balanced with discomfort it caused,” Alles said. “There are other ways to teach satire or about that time period without involving that discomfort.”

Provenzano said it’s important not to shy away from any literature solely because it’s difficult to discuss or makes people uncomfortable.

“There were the issues of race and language that were part of the conversation,” Provenzano said. “It was a conversation that wasn’t easy, but sometimes the toughest things are the best things to teach.”

Provenzano did acknowledge that perspective plays a large and important role in the way students read “Huckleberry Finn.”

“I’m a white male and I’m not an African American student, so I can never fully understand how it feels to read this book and see that word or have that word discussed,” Provenzano said.

This update to the curriculum didn’t mean simply replacing one American classic with another, but looking for more contemporary literature. As Peck put it, all of the current core literature was written by long dead white men.

“The staff spent last year looking and working through some texts that could take the place of “Huckleberry Finn,” but that is still where we are currently,” Bur said. “We continue to look for that exemplar text.”

The lack of a replacement isn’t due to a lack of effort, and initially both the North and South English Departments sought out and selected multiple books that might have been viable, according to Peck.

“The North and South English Departments got together and we had a pretty methodical way of going through books: we decided on criteria for texts we would like to see and even rankled the criteria by importance,” Peck said. “We looked at a broad set of books from stuff that other schools are teaching to books that have won awards, etc.”

According to Burne, it’s important that students are learning about satire, a key element of “Huckleberry Finn,” along with important themes of race, diversity and American history.

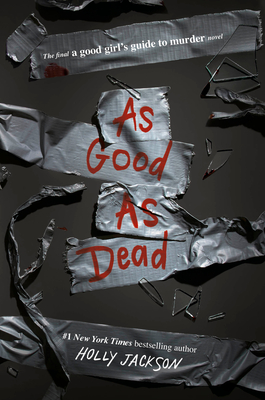

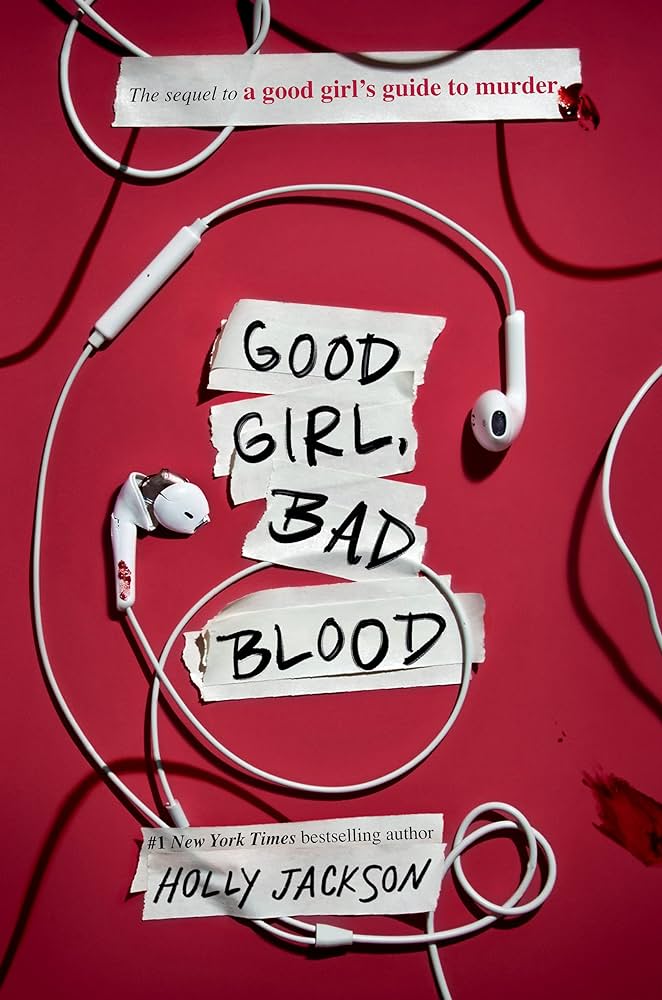

“Sing Unburied Sing” and “The Hate U Give” were frontrunners in the department’s search for new, diverse literature that could possibly replace “Huckleberry Finn,” according to Bur.

“We thought (the books) were contemporary voices that reflected both the female and African American experience in America, something our curriculum certainly lacked,” Peck said. “So we read both of them, some parents read them and lots of students read them.”

The staff, students and parents who read the book all gave their feedback or submitted reports due around the beginning of school, according to Peck.

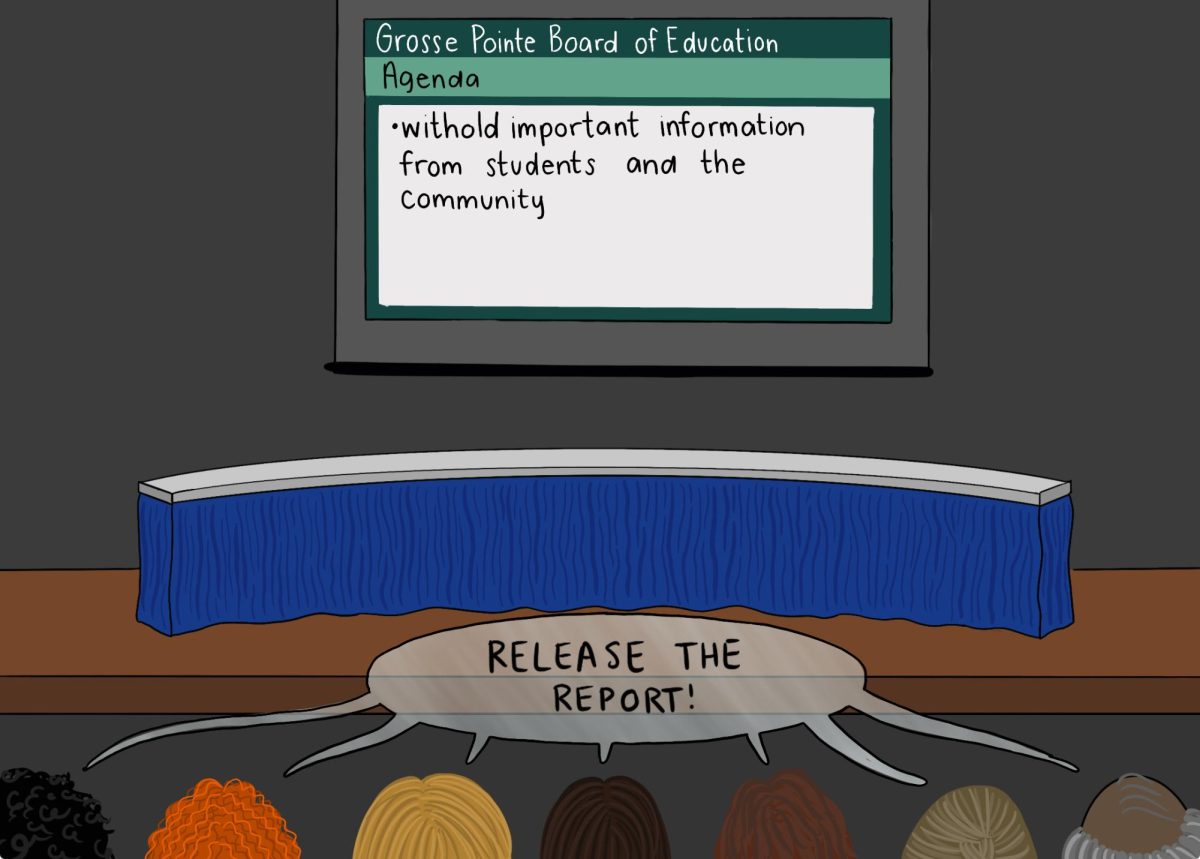

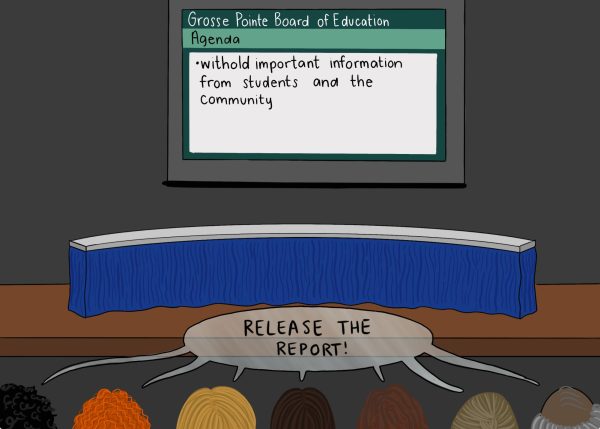

However, one week before that due date, the English Departments of both schools were informed that they were not to move forward with either of the books.

“We felt that it was appropriate to take a step back and examine more books to ensure that we are putting the right book forward,” South Principal Moussa Hamka said. “For example, we felt ‘The Hate U Give’ uses the F-word too many times — it was too vulgar.”

Burne said he was also concerned about the content and integrity of the possible books.

“It’s a young adult novel, so as a district that strives for preparing students for collegiate level, I’m not sure that a young adult novel is valuable is a high school setting, especially in a tenth grade classroom would be the most appropriate,” Burne said. “(The books) also had some adult situations, including sex and drug use that would have been problematic, I think, for many of members of our community.”

Anna Abundis ’20 read both “The Hate U Give” and “Sing, Unburied, Sing” this summer as part of the student review process for possible replacements.

According to Abundis, her job was to read the books and evaluate if they were fit for the curriculum, and if teens would actually be interested in reading them. Abundis acknowledged the difficulty of both, but still said either could be used in class, in her opinion.

“In “The Hate U Give” there’s a lot of controversy surrounding police brutality, and yes, the book is supposed to make you feel uncomfortable, but it could be that it just makes people feel too uncomfortable, so they didn’t want to use it,” Abundis said.

Without a suitable replacement for “Huckleberry Finn”, the English department will be moving on with plan b: a still not set-in-stone plan that will involve short stories, poems and different forms of literature that highlight the diversity of American authors, according to Hamka.

“We are replacing it temporarily with a text centered unit that highlights underrepresented or minority voices, and the themes their voices raise,” Hamka said.